|

This is an electronic version of “Re-Visions,” the Preface to the revised edition of Beowulf and the Beowulf Manuscript (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1996), pp. xv-xxviii. |

Re-Visions [Preface]Kevin KiernanIn the fifteen years since the first edition of Beowulf and the Beowulf Manuscript, the dating of Beowulf has remained a highly charged, controversial topic, and the study of Old English manuscripts in general has flourished. Although determined proponents for any time between the eighth and the eleventh century make a consensus on the dating of Beowulf perhaps more unlikely today than ever before, the early eleventh-century manuscript remains our only primary evidence for whatever theories we have about the ultimate origin of the poem. The most important recent controversy concerns the paleographical dating of the manuscript. In "Beowulf come lately: Some Notes on the Palaeography of the Nowell Codex," David N. Dumville gives a new interpretation of Neil Ker's dating notation, s. x/xi, for the handwriting of the Beowulf manuscript. According to Dumville, the handwriting of both scribes must fall somewhere between 997 and 1016, specifically between the midpoint of the reign of Æthelred the Unready and his death.1 His interpretation pointedly excludes the reign of Cnut the Great for the time of the manuscript and so also for the composition of the poem (63). In making his case Dumville "represents, in a sentence, the progression of argument" in Beowulf and the Beowulf Manuscript: "Kiernan sought to establish that the poem was composed in the reign of Cnut, king of England 1016-35, and then to show that the manuscript-evidence fitted admirably with this, while that of language did not disagree" (49 and n. 5). Pivoting on the word "then," his sentence actually reverses the progression of my argument, which is entirely predicated on Ker's paleographical dating of the manuscript. On the first page of chapter one I say, "Paleographical dating places the [p. xv] MS at the end of the 10th century or the beginning of the 11th, or, roughly speaking, between the years 975 and 1025" (13). Cnut the Great only came into the picture because his reign falls within Ker's fifty-year dating range.2 Dumville also maintains that I have not confronted "the evidence of paleography — as opposed to codicology — in the search for a date for Beowulf" (49-50). On the contrary, my discussion of the palimpsest on folio 179 depends on an exhaustive paleographical study of all letter-forms by Tilman Westphalen.3 I underscore his results with a paleographical description of the letter a: The development of the a form is the most convincing of all: it has gone from a sharp quadrangular form to a rounded triangular form, resembling a modern cursive a. Its variants are either rounded or pointed at the top. The incipient development of this new letterform can occasionally be observed on other folios (when the left side of the quadrangular a is shorter than usual, for example), but the rate of occurrence on other folios is minimal. (BBMS 223 n. 48) My paleographical discussion of the "quadrangular" letter a thus anticipates Dumville's own discussion of the same letter as a defining feature of English Square minuscule: A form of Insular minuscule, its singular defining characteristic has always seemed to be the systematic use of a form of the letter a, found very occasionally in earlier Insular script, in which an open a is in effect topped by a separate and straight stroke.... However, definition of a script type by a [p. xvi] single letter form is an unhappy task for, inevitably, there are many specimens of Square minuscule in which it fails to occur consistently or at all.4 Elsewhere I anticipate his paleographical observation that, "if the work of Scribe A and Scribe B had been found in complete independence of one another, Hand A would have been dated 's. xi in.' or 's. xi1', while Hand B would probably have been dated 's. x ex.'"(55). As I put it, without the transitional gathering uniting the two scripts, "paleographers would have every reason to conclude that the two gatherings preserving Beowulf's fight with the dragon had been copied many years before the five preserving Beowulf's youthful exploits in Denmark" (257). We do not seem so far apart, then, in our representations of the paleographical setting. While he at first takes me to task for assuming that the manuscript is really early eleventh century, rather than late tenth or early eleventh, Dumville comes to the same conclusion after arguing that the characteristics of the first scribe's handwriting are never found in datable tenth-century manuscripts. We do not agree that the appearance of late Square minuscule in the second part of Beowulf must be arbitrarily restricted to the first sixteen years of the eleventh century. Dumville says that "there is neither evidence nor need to attribute a lingering death to Square minuscule" (63), yet the occurrence of other manuscripts dated by Ker s. x/xi with late Square minuscule alongside recognizably eleventh-century hands constitutes such evidence. He also acknowledges that "within Hand B there is some evidence for scribal development and adaptation to more modern forms" (50 n. 7). The evidence he alludes to here is the appearance of two later stages of the scribe's Square minuscule on folio 198 verso, the last page, and folio 179 recto and verso, the palimpsest. Even if Dumville had evidence that the second scribe copied his part by 1016, late Square minuscule is not only lingering but actually developing into a rounder script in these later manifestations. A closely datable example of Square insular script survives in a chirograph of Bishop Byrhteh of Worcester (1033-38) leasing land to [p. xvii] his cniht Wulfmær.5 A chirograph is a contract executed in duplicate or triplicate on the same sheet of vellum with the word CYROGRAPHUM separating the copies. The parts are distributed to the donor and donee(s) by cutting the leaf through the word CYROGRAPHUM.6 In this case the bottom copy survives, for lower portions of the word appear at the top of the document.

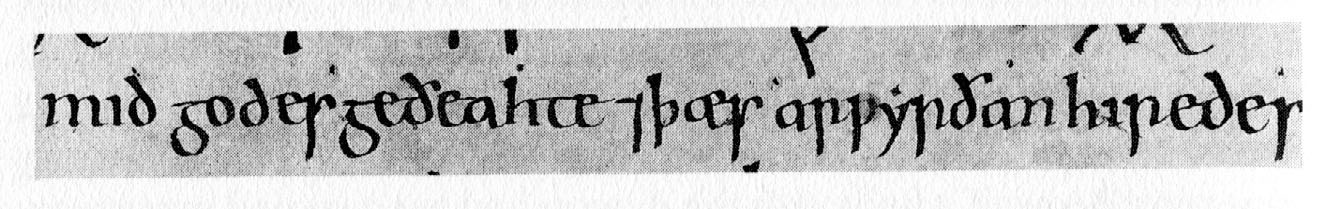

This late appearance coming from a main center such as Worcester suggests that the continued use of Square minuscule was deliberately nostalgic. The scribe's rejection of Caroline influence is evident throughout, but is particularly noticeable in the exclusive use of low insular s (29 times). The four-sided a has a number of variants, including flat-topped and somewhat rounded varieties (as in the case of the later hand on folio 179 of Beowulf), but there are no triangular forms. Although there is an incipient roundness to the script, which is probably induced by the large size of the document, the overall aspect of the lettering on the page is "square," enhanced by the relatively short descenders and ascenders. This specimen of late Square minuscule was written at the end of Cnut's reign or during the reign of his son, Harold Harefoot. Fortunately there is no reason to continue arguing over the interpretation of Ker's ambiguous dating notation of s. x/xi. A dozen years after the publication of his Catalogue, Ker unambiguously dated the Beowulf manuscript between 990 and 1040, which includes the reigns of both Cnut and his son.7 As Ker says in his paleographical commentary on The Will of Æthelgifu, [p. xviii] The failure of Anglo-Saxon minuscule at the end of the tenth century led to a period of some fifty years, approximately 990 to 1040, during which there was great variety in the writing of books and charters in England, with some good writing and, especially in the vernacular, much rather poor imitative writing with no character of its own. In this period great differences are to be seen between the hands of scribes writing at the same time and in the same place, between, for example, the first and the second hand of Beowulf.... These examples illustrate the impossibility of dating script of this period at all closely, and in particular hands which are either dully imitative like our scribe's or which have gone some way towards Caroline minuscule, like the first hand of Beowulf....(45-46) It was Ker's mature judgment, then, that the Beowulf manuscript might well have been written during or even after the reign of Cnut. The relative rarity of manuscripts in which Square minuscule occurs alongside the new eleventh-century minuscule opens some intriguing possibilities about the provenance of the Beowulf manuscript. Another case is the Blickling Homilies manuscript (Princeton, Scheide Library MS 71), which Ker assigns the same date for the same reasons.8 It is clear that neither manuscript comes from a scriptorium where uniformity of script was enforced or even encouraged, for in both manuscripts scribes with old-fashioned, Square scripts are paired with scribes with more up-to-date, Caroline tendencies. Scholars have known for over a century about the case of literary borrowing between the description of Grendel's mere in Beowulf and St. Paul's vision of Hell in Homily 16, and Rowland Collins has now shown in a convincing analysis of the parallel phrasing that the passages in Beowulf are based on the homily.9 The closely related texts and the coincidental use of late Square minuscule in the early eleventh century, if as rare as Dumville maintains, would be most easily explained if the two manuscripts derive from the same scriptorium. There are paleographical and codicological reasons to suspect that they do have a common provenance. In his discussion of the date of [p. xix] the manuscript, Max Förster observed that "The hand of the second Beowulf scribe displays in overall appearance a striking resemblance to the first scribe of the Blickling Homilies, so that both must belong to approximately the same period."10 Förster undoubtedly recognized the many significant differences in specific letterforms, and Ker rightly omits the two manuscripts from his tally listing closely similar hands (lvii). Another difference is that the Blickling scribe was calligraphic, paying attention to the details of his letterforms, whereas the Beowulf scribe was almost crudely utilitarian. Their differences notwithstanding, anyone who has used both manuscripts cannot fail to be impressed by what Förster calls the "overall appearance" — the general proportions, the striking resemblance in the duct, the similarity in angle and width of the quill. Indeed, the similarities in general aspect are more immediately evident than the specific differences. At a glance one gets the uncanny impression of what the second scribe's part of the Beowulf manuscript looked like before the fire. Greatly contributing to the broad paleographical resemblance between the first hand of the Blickling Homilies and the second hand of Beowulf is the virtually identical size of the writing grids. The grids of the Homilies were ruled for 21 lines of text (some pages contain 22 lines, the extra line added without rulings); those of the first Beowulf scribe were ruled for 20 lines (with one gathering ruled for 22 lines, and another containing four consecutive pages with 21 lines of text); and those of the second scribe were ruled for 21 lines, like the Homilies. Even including three gatherings from the Homilies that have slightly longer grids (the 12th, 13th, and 14th), and two gatherings from Beowulf that have slightly wider ones (the last two), the approximate numbers Ker gives for the Beowulf manuscript (ca. 175 x 105 mm) and for the Blickling manuscript (180 x 108 mm) would serve both manuscripts equally well.11 In fact, no other manuscript in the more than 400 described in Ker's entire Catalogue comes as close to Beowulf as the Blickling Homilies manuscript in the combination of line numbers [p. xx] and grid size. If both manuscripts derive from the same scriptorium, its one telling uniformity was that it produced books with text faces of the same relative size, even when the rulings vary from 20-22 lines per page. A more subtle codicological similarity between the two manuscripts is that all four of the scribes are quite inconsistent in the way they arrange the hair and flesh sides of the vellum sheets within gatherings. Ker regards sheet arrangement as a criterion of both date and provenance (xxv). Hair and flesh sides often contrast noticeably in color and texture, and the normal insular practice for manuscripts of this period was to place hair sides against hair sides, and flesh sides against flesh sides, to obscure the contrast on facing pages.12 Our scribes ignore this trend. The same odd mixture of format occurs in the Blickling Homilies manuscript as in the Beowulf manuscript: sometimes the contrast of hair and flesh sides is carefully obscured, while sometimes it is deliberately displayed, with flesh on the outside of all leaves in a gathering in the Homilies, and hair on the outside of all leaves in Beowulf (second scribe, and first scribe, first gathering). This shared lack of uniformity, also evident in the ill-matched script, begins to look like a distinctive feature of a particular provincial scriptorium. While all of the evidence is circumstantial, it seems rash to ignore these textual, paleographical, and codicological coincidences. If we admit the possibility that the two manuscripts were copied at different times in the same scriptorium, the Blickling manuscript provides a specific literary source for Grendel's mere as well as a specific locale for the composition of Beowulf. The Blickling manuscript has ties going back to the Middle Ages to Lincoln,13 in the heart of Danish Mercia, where Scandinavian traditions would be strong and where the dialect of Old English would be influenced by its Anglo-Danish speakers. The Blickling Homilies manuscript is a composite codex, put together to some extent in coherent booklets, presumably so that one section might be used apart from or at the same time as other sections. [p. xxi] For example, Homily 4 is self-contained in the fourth and fifth gatherings, whereas Homilies 5 and 6 are inseparable in the next two gatherings. To create these coherent booklets, the scribe had to abandon his normal practice of using four-sheet gatherings. He used a single folded sheet for gathering five, all that he needed to finish the homily.14 Similarly, the scribe added a sheet to gathering seven in order to make a separate unit for the two following homilies. The first scribe of the Beowulf manuscript seems to have made a separate booklet of Beowulf by taking a sheet from the preceding four-sheet gathering and using this bifolium as the first gathering of the poem. Previous descriptions of the Nowell Codex assumed that the first two folios of Beowulf were the last two folios of the preceding prose collection. A variety of evidence, including the worn appearance of its first page and an account of the codex before the fire of 1731, persuaded me instead that the scribe took pains to start Beowulf with a fresh gathering.15 The most compelling evidence was that both scribes carefully corrected copying errors in Beowulf, while no one even seemed to notice egregious errors in the prose part of the codex. Because both scribes treated Beowulf as if it were a separate book, I looked for ways in the collation of the vellum sheets that the first scribe might have separated the poem from Alexander's Letter to Aristotle, the last prose text. A collation of the hair and flesh patterns showed that the prose codex, not counting the last controversial gathering, was constructed of five, three, four, and four sheets. Both of the four-sheet gatherings, however, had nonconjugate leaves at the third and sixth positions, showing that the scribe had in both cases augmented original three-sheet gatherings. In this light three-sheet gatherings were the norm, making it natural for the scribe to end the prose codex with a [p. xxii] three-sheet gathering if that was all that was needed to finish Alexander's Letter. Collation of the following ten leaves indicated that, if Beowulf began a new codex, the scribe most likely augmented an original four-sheet gathering (the norm in the Beowulf manuscript) to a five-sheet gathering by adding nonconjugate leaves at the fourth and seventh positions. Based on a careful measurement and collation of all the rulings on these and surrounding folios, however, I revised this view in 1982. As I reported that year at a special session on my book at the Modern Language Association, The first two sheets of the three-sheet gathering, fols. 123 + 128 the outside sheet and fols. 124 + 127 next, were almost certainly ruled one on top of the other, since the top sheet has strong, primary rulings, while the second sheet has virtually invisible ones. The third, or inside sheet (fols. 125 + 126) was ruled separately, since its rulings are again strong. The leftover sheet used for the first four pages of Beowulf (fo1s. 129 +130) was also ruled separately, as its unusually heavy rulings, perhaps the heaviest in the codex, clearly reveal. The rulings showed that the scribe apparently pulled a sheet from a four-sheet group already pricked but not yet ruled for the last prose gathering and used the single bifolium for the first gathering of Beowulf. The revised view explains why the measurements of the rulings on fols. 129 and 130 are closer to the measurements of the preceding pages than they are to the following pages. It also accounts for the uniquely heavy ruling on folios 129 verso and 130 recto, the facing pages of the proposed bifolium.16 These rulings do not match up with the first two leaves of the last prose gathering. Nor do indentations from the heavy rulings on folio 129 verso carry through to 128 verso, the last page of the prose codex, as they should have done if the first two leaves of Beowulf were part of a four-sheet gathering at the end of the prose codex. On the contrary, folio 128 was independently ruled, as the faulty ruling extending beyond the margin at the end of line 10 unequivocally reveals. [p. xxiii] Whether or not Beowulf was copied as a separate codex, we should not lose sight of the more important fact that both scribes treated the poem, unlike the prose texts that precede it, as an important text worthy of their special attention. Both scribes carefully and repeatedly proofread their work and the second scribe even made corrections in the first scribe's section of the poem. Neither scribe proofread the prose codex. The intelligence and thoroughness of the scribal proofreading disproves the old notion that the language of Beowulf was somehow incomprehensible to the people copying the text in the early eleventh century. Linguistic tests for early dating seemed unassailable in the late 1970s, when a well-known medieval journal turned down the advice of three referees to publish a version of my first chapter on linguistic dating. Yet if any consensus on time-honored Beowulf controversies has formed over the past sixteen years, it is that the language of the poem can no longer be used to date the poem early rather than late. The turning point was achieved in 1980 and 1981 by editors of the Dictionary of Old English project, who did not take a stand on whether the composition of Beowulf was early or late, but only insisted that the linguistic tests were inconclusive and that the mixture of forms in the manuscript was not in fact unnatural in a late Anglo-Saxon scriptorium.17 Although some metrists in particular remain unconvinced, most published accounts now seem to agree that the language of the poem cannot be used to rule out a late dating. Old English metrical theory is historically tied to an early dating. Its practitioners have argued from the heyday of nineteenth-century philology that metrical analysis can recover, or reconstruct, the ancient text supposedly ruined by the scribes of the Beowulf manuscript and their equally inept precursors in the intervening centuries. The argument in a nutshell is that reconstructed early linguistic forms fit the meter of Beowulf better than the words that actually appear in the late Anglo-Saxon manuscript. Nineteenth-century philologists were thus devoted to the reconstruction of presumed earlier stages of the language, not to the examination of an existing language surviving in [p. xxiv] manuscripts. In a sustained effort to revitalize this approach, R. D. Fulk has recently reaffirmed all the old dating arguments in A History of Old English Meter.18 He even reformulates a neogrammarian sound law he calls Kaluza's Law,19 which he uses as a criterion of early date, even though it applies uniquely to Beowulf. Adopting the "presumed chronology" of the nineteenth-century philologists who established the dating arguments, Fulk seemingly eliminates the possibility of seeing alternative interpretations of the impressive amount of data he usefully assembles. The importance of metrical studies is that they can provide detailed linguistic insights otherwise hidden from us. It is unfortunate that in Anglo-Saxon studies these insights have always been channeled away from the manuscripts and the times that furnish them. The important observations made by metrists from the time of Sievers onward are not incompatible with late dating. It is widely if not universally agreed that most of our extant manuscripts, including Beowulf, are written in a standard Late-West-Saxon literary dialect used throughout Anglo-Saxon England in the early eleventh century. This literary dialect thus conceals in its standard spellings dialectal features of non-West-Saxon areas, just as our own standard literary dialect conceals, say, various pronunciations among British dialects. Late-West-Saxon spellings, in other words, do not reflect late non-West-Saxon pronunciations, just as the same spellings do not reflect early phonology. Close attention to meter can reveal some of these late pronunciations. For example, although the standard Late-West-Saxon literary dialect did not include uncontracted spellings of the infinitives for "do" and "go" (don and gan), we can be confident that these words had disyllabic pronunciations in Beowulf because the meter requires it. Similarly, the meter of Beowulf shows that some words spelled with two syllables were in all likelihood pronounced monosyllabically, despite their spellings. The nineteenth-century philologists interpreted this evidence as proof that the poem predated a sound change known as West Germanic parasiting, or epenthesis, the intrusion of a vowel before some resonant consonants like r. Another explanation, however, is that the pronunciation reflects a North Germanic, or Anglo-Danish, dialect of Old English [p. xxv] spoken in eastern England in the early eleventh century.20 Such a dialect of Old English would account as well for the continued alliteration of palatal and velar g ([y] and [g]) long after palatalization of g before front vowels took effect in West Saxon dialects. Historical linguists must begin to explore areas like the Danelaw for evidence of late non-West-Saxon phonology in late manuscripts. The name "Beowulf" itself may show the same Scandinavian influence on the Old English dialect of the poem . The spelling "Biowulf," which occurs fourteen out of seventeen times in the second scribe's part of the manuscript, may attest a late North Germanic pronunciation with a palatal glide, as the modern Danish spelling "Bjowulf" still does. In any case, the spelling provides previously unnoticed support for the thesis that the version of Beowulf that has come down to us was first put together from two different sources in the surviving manuscript. Close scrutiny of the three remaining eo-spellings of the name reveals that at least two of the cases, and probably all three, were later altered from original io spellings. The first eo spelling occurs on folio 173r14, the first time the second scribe uses the name after taking over from the first scribe. The eo is a correction, however, of a previous reading:

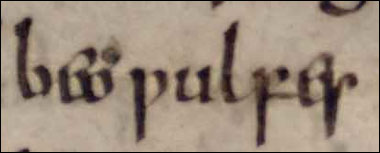

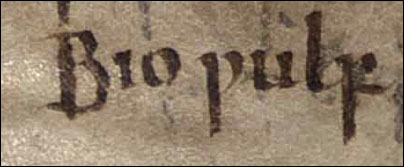

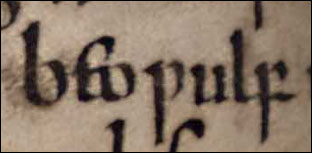

The stages of this "correction" are revealing. The scribe first wrote io, and then in attempting to change it to eo mistakenly drew the high e-head from the first side of the o instead of from the top of the i. While [p. xxvi] the ink was still wet, the scribe blotted out the mistake and correctly redrew the e-head where it belongs. The io spelling was not a mistake, as the fourteen additional examples testify. The scribe apparently made the change to conform with the first scribe's practice. However, when the name next appears on the following page (173v20), the scribe has not only used the io spelling, but also a capital B for the first and only time, as if to assure us that the spelling "Biowulf" in this section of the manuscript is no mistake:  The scribe also changes an original io spelling of the name on folio 185v13 by imperfectly drawing an e over the original i — the e-head sits particularly uneasily on the underlying io.  The only doubtful example comes from folio 179, where, according to Julius Zupitza, "all that is distinct ... was freshened up by a later hand." Farther down the page, however, there is a very clear example of an alteration of biorn to beorn (179rl2). An Anglo-Dane would no doubt be more comfortable with the first spelling. While the triumph of nineteenth-century philology was its reconstruction of early linguistic forms not found in extant manuscripts, twentieth-century technology — in particular, fiber-optics, electronic photography, and digital image processing — are enabling us to reconstruct linguistic forms that are damaged or otherwise illegible in our surviving manuscripts.21 Fiber-optic light provides a cold, bright light [p. xxvii] source that can be safely used for many purposes in reading manuscripts. By holding it behind the nineteenth-century frames that protect the burnt edges of the manuscript, for example, one can easily see whatever is covered by the frames. For ease of reference, the appendix in this edition provides a list of the hundreds of letters and parts of letters first revealed by this method.22 Until the advent of digital technology, there was no practical way to reproduce the hundreds of backlit readings. With the aid of a digital camera and digital image processing, however, I am now preparing digital facsimiles of all of these covered readings as part of the Electronic Beowulf project. Manuscript studies will benefit in many ways from the development of digital technology. Unique manuscripts are by definition relatively inaccessible, sometimes as hard to get hold of as they must have been in Anglo-Saxon times, and curators are properly reluctant to subject them to unnecessary use. The most important recent development for scholars of manuscripts is the advent of inexpensive, high-resolution, full-color, electronic facsimiles. These new facsimiles are beginning to provide unprecedented access to manuscript resources for teaching and research. They will soon make it possible to undertake serious and reliable manuscript research — even to investigate the construction of gatherings, for example, or to study parts of a text that are not visible under ordinary circumstances — without using and without needing to use the actual manuscript. They can let us see at high magnification dry-point rulings and glosses, the color and texture of vellum, changes in ink, scribal erasures and alterations, and countless other things without traveling to a distant library. The versatility of high-resolution electronic facsimiles in full color has surprisingly mitigated my closing caveat in the preface to the first edition that "paleographical and codicological facts must ultimately be evaluated, as they can only have been gathered, by direct and prolonged access to the MS ... " (xiii). While the unique Beowulf manuscript will always have the last word, extraordinary digital facsimiles may give us the first clear glimpse of important aspects of it in a thousand years. [p. xxviii] |

Notes1. Archiv für das Studium der neueren Sprachen und Literaturen 225 (1988): 49-63. 2. The span from 975 to 1025 is a conservative interpretation of his dating notation. "All my dates are certainly not right within the limits of a quarter-century," Ker says. "I can only hope," he adds, "that not too many of them are wrong within the limits of a half-century." Catalogue of Manuscripts containing Anglo-Saxon (Oxford,1990), xx. 3. Beowulf 3150-55: Textkritik und Editionsgeschichte (Munich, 1967), 58-69. The foliation best used for citations to Beowulf is the one written on the manuscript itself. For an explanation of the inaccurate official BL foliation, see the excellent article by Andrew Prescott, "'Their Present Miserable State of Cremation': The Restoration of the Cotton Library," forthcoming in Sir Robert Cotton as Collector, ed. C. J. Wright (British Library Publications). 4. "English Square minuscule script: the background and earliest phases," Anglo-Saxon England 16 ( 1987): 153. 5. British Library Additional Charter 19,797 (Sawyer 1399). Its authenticity is not in doubt. There is a facsimile in Wolfgang Keller, Angelsächsische Palaeographie (Berlin, 1906). 6. On chirographs see H. D. Hazeltine, "General Preface," Anglo-Saxon Wills, ed. Dorothy Whitelock (Cambridge, 1930), xxiii-xxvi. 7. The Will of Æthelgifu (Oxford, 1968), 45-46. I added a reference to this in the reprint of "The Legacy of Wiglaf: Saving a Wounded Beowulf," Beowulf: Basic Readings, ed. Peter S. Baker (New York, 1995), 218 n. 66. 8. Catalogue, 454. There is a facsimile edited by Rudolph Willard, The Blickling Homilies, Early English Manuscripts in Facsimile 10 (Copenhagen, 1960). 9. See Richard Morris, The Blickling Homilies of the Tenth Century, Early English Text Society o.s. 58, 63, 73 (1880), vi-vii; and Rowland L. Collins, "Blickling Homily XVI and the Dating of Beowulf," Bamberger Beiträge zur Englischen Sprachwissenschaft 15 (1983): 61-69. 10. Die Beowulf-Handschrift, Berichte über die Verhandlungen der Sächsischen Akademie der Wissenschaften zu Leipzig, philologisch-historische Klasse 71 (1919) : 43 (my translation). 11. The shrinkage of the vellum from fire damage in the Beowulf manuscript is negligible, except along the right margin. There is, of course, considerable variation in the hand-drawn rulings in both manuscripts, but sometimes the rulings between manuscripts are identical in measurement. 12. See Rowland L. Collins, "The Blickling Homilies," Anglo-Saxon Vernacular Manuscripts in America (New York, 1976), 52-57; and D. G. Scragg, "The homilies of the Blickling manuscript," Learning and Literature in Anglo-Saxon England, ed. Michael Lapidge and Helmut Gneuss (Cambridge, 1985), 299-316. 13. Lincoln officials recorded their nominations and elections in its margins for several centuries, beginning in 1304. See J. W. F. Hill, Medieval Lincoln (Cambridge, 1965), 291-92, 400-401; and Willard (48). 14. Willard's collation is authoritative, because he studied the gatherings with the binding removed in the mid-1950s, when the facsimile was in preparation. Scragg (1985) nonetheless rejects his description of the fifth gathering, asserting that it is two nonconjugate leaves rather than a bifolium. My own collation (1980, 1983) corroborates Willard's description, a single folded sheet (with flesh on the outside) . 15. The clear "Vi" at the bottom of the page is possibly in the same early modern hand and ink as "Laurence Nouell 1563" on folio 91(93) recto; if so, it predates Cotton's ownership and may be a quire signature supplied by Nowell himself. In any case, having failed with special lighting and image processing to read anything following "Vi," I no longer believe that "V[tellius] A 15" was once there (133-34). 16. While proofreading in 1980, I mistakenly revised a comment that "primary rulings were made on the recto, not the verso of fol. 130." My notes from the manuscript confirmed that the description was accurate, but in the context I thought I must have meant folio 129, the first folio of Beowulf. On what eventually became page 134, I therefore "corrected" 130 to 129 and added some seemingly relevant comments about the heavy ruling of folio 129 instead of 130. 17. See Ashley Amos, Linguistic Means of Determining the Dates of Old English Literary Texts (The Medieval Academy, 1980); and Angus Cameron, Amos et al., "A Reconsideration of the Language of Beowulf," The Dating of Beowulf, ed. Colin Chase (Toronto, 1981), 33-75. 18. (Philadelphia, 1992). 19. Max Kaluza's work on Old English meter is conveniently translated by A. C. Dunstan, A Short History of English Versification (London, 1911) . 20. There are other possible explanations. As Geoffrey Russom says in a section on "Dating Paradoxes," "The relatively large number of examples requiring archaic forms ... may suggest that vowel contraction and epenthesis began to occur just before the composition of the poem. Such appearances may be deceptive. The Beowulf poet employed a formulaic diction with a vocabulary and syntax characteristic in many respects of a much earlier period.... Underlying representations in a synchronic grammar of a given period sometimes correspond to forms that disappeared from speech hundreds of years previously." Old English Meter and Linguistic Theory (Cambridge, 1987), 43. 21. For an overview of techniques applied to Old English manuscripts, see my "Old Manuscripts / New Technologies," Anglo-Saxon Manuscripts: Basic Readings, ed. Mary P. Richards (New York, 1994), 37-54; and "Digital Image-Processing and the Beowulf Manuscript," Computers and Medieval Studies, ed. Marilyn Deegan with Andrew Armour and Mark Infusio, Literary and Linguistic Computing 6, no. 1 (1991): 20-27. 22. "The state of the Beowulf manuscript, 1882-1983," Anglo-Saxon England 13 (1983): 23-42. |