Kentucky Pest News Newsletter

HIGHLIGHTS IN THIS ISSUE

Number 1029__________July 12, 2004

CORN

SOYBEAN

VEGETABLES

FRUIT

SHADE TREES AND ORNAMENTALS

PESTS OF HUMANS

MISCELLANEOUS

DIAGNOSTIC LAB HIGHLIGHTS

IPM TRAP COUNTS

CORN

DRY SOILS COULD SPELL TROUBLE IN CORN FIELDS WITH ROOT ROTS

By Paul Vincelli

Many corn fields experienced long periods of wet soils

after planting. When soils are generally wet to saturated

early in the season, the corn plant produces a shallower

root system than in seasons when periods of drying take

place. Compounding this situation is the fact that root rots

have been diagnosed in a number of instances in Kentucky

corn fields, principally root rot caused by the fungus

Fusarium verticillioides (formally known as Fusarium

moniliforme, the same fungus that can produce fumonisins

in the grain). Root rot caused by F. verticillioides is

typically triggered by some stress to the plant, including

herbicide injuries. Pythium root rot is favored by soil

saturation, so fields with poor drainage (either poor

surface drainage or poor internal soil drainage) are prone

to this problem.

Many corn fields experienced long periods of wet soils

after planting. When soils are generally wet to saturated

early in the season, the corn plant produces a shallower

root system than in seasons when periods of drying take

place. Compounding this situation is the fact that root rots

have been diagnosed in a number of instances in Kentucky

corn fields, principally root rot caused by the fungus

Fusarium verticillioides (formally known as Fusarium

moniliforme, the same fungus that can produce fumonisins

in the grain). Root rot caused by F. verticillioides is

typically triggered by some stress to the plant, including

herbicide injuries. Pythium root rot is favored by soil

saturation, so fields with poor drainage (either poor

surface drainage or poor internal soil drainage) are prone

to this problem.

Fields of corn with root systems that are shallow due to

post-planting rains and damaged by root-rotting infections

will have a difficult time filling grain should weather

conditions turn dry. All one can do at this stage is adopt a

wait-and-see attitude. However, for fields that dry down

quickly during harvest, it would be valuable to review the

overall production system for stresses: the

appropriateness of hybrid selection, the weed control

program, degree of soil compaction, fertility, etc. The UK

Extension publication, A Comprehensive Guide to Corn

Management, ID-139, is an excellent resource for such a

purpose.

For information about corn pests, visit

"Insect Management Recommendations".

SOYBEAN

COULD SOYBEAN RUST BE IMPORTED INTO THE UNITED STATES WITH SEED, BULK GRAIN OR MEAL?

By Don Hershman

Few scientists I have talked with, or heard speak, believe

agricultural commerce will be the means by which

soybean rust (SBR) makes its way into the continental

United States. Having said this, everyone I have heard

speak on the topic also feels it is not an impossible

scenario.

Few scientists I have talked with, or heard speak, believe

agricultural commerce will be the means by which

soybean rust (SBR) makes its way into the continental

United States. Having said this, everyone I have heard

speak on the topic also feels it is not an impossible

scenario.

The SBR pathogen, Phakopsora pachyrhizi, is not seed-borne,

but it could infest trash in seed and bulk grain. This,

however, is a remote possibility for a variety of reasons.

First, soybean is harvested AFTER plants drop their leaves.

Thus, the vast majority of rust-infected leaves will be on

the ground when the crop is harvested. Secondly, even if

some dead leaves with rust make there way into harvested

seed/grain, the chances are very high that the fragile

urediniospores of P. pachyrhizi would die soon after

harvest. Finally, it is my understanding that seed and bulk

grain produced in Brazil are almost always processed

through cleaners and dryers following harvest. This

further reduces the chances that viable rust spores will

contaminate those products. Of course, meal is even

further processed, compared to seed and bulk grain.

On the other hand, SBR can be present in all above-ground

plant parts, including pods and stems. Thus, if a seed lot or

bulk grain shipment is contaminated with SBR in pods or

stem pieces, the risk for bringing in P. pachyrhizi with seed

and grain may be increased. I say may, because I really do

not know. This type of information - specifically, the

survival characteristics of urediniospores of P. pachyrhizi -

have been studied very little.

At present, there are no published data indicating how

long Phakopsora pachyrhizi urediniospores could survive in

a shipment of soybean seed, grain or meal. At a conference

in St. Louis hosted by the American Soybean Association

this past January, I heard that it takes a minimum of 60

days for a bulk grain shipment of soybean to make its way

into a U.S. port following harvest. The period for seed

could be significantly shorter. Under normal

circumstances, the SBR fungus would not be expected to

survive in trash for this length of time. A concern was

raised at the meeting that urediniospores might remain

viable in containment longer than we think because of the

higher moisture level and lack of light in the hull of a

cargo ship. There is a great need for research to be

conducted in this area.

In the meantime, officials with the Animal and Plant

Health Inspection Service (APHIS) are on high alert and

are closely scrutinizing each shipment of soybean whose

port of origin is a county with known infestation of SBR.

When I searched the World Wide Web on this topic, it

became clear that there is a great deal of unrest and

concern by all parties involved that we do everything

possible to keep SBR from being imported with moving

seed, grain, and meal shipments.

Most scientists at this time are still convinced that SBR will

naturally make its way into this country as a result of

wind-blown urediniospores from South America, or

perhaps in the winds of a hurricane system originating

over Africa.

I will conclude with a statement made in a February 23,

2004 USDA-APHIS report entitled "Status of Scientific

Evidence on Risks Associated with the Introduction into

the Continental United States of Phakopsora pachyrhizi With

Imported Soybean Grain, Seed, and Meal":

"Soybean leaf debris associated with "foreign material" found in

soybean grain presents a theoretical pathway for the

introduction of SBR. However, normal commercial practices

minimize the presence of "foreign material" to less than 2%.

Moreover, as it is a normal commercial practice to harvest

soybeans after the plants have been defoliated, leaf debris should

compose only a fraction of the "foreign material"; therefore,

making "foreign material" found in grain an unlikely pathway

for introduction of SBR."

For more information about soybean pests, visit

"Insect Management Recommendations".

FRUIT

GREEN JUNE BEETLE AND FRUIT CROPS

By Ric Bessin

As fruit crops begin to ripen across the state, one insect

pest is almost certain to cause problems, the green June

beetle. Unlike the Japanese beetle that is primarily a leaf

feeder, although it will attack damaged fruit and sound

fruit on occasion, the green June beetle almost exclusively

feeds on the fruit. It may be easier to list fruit that this pest

does not attack as most of the fruit crops are vulnerable.

Growers of peaches, apples, grapes, blueberries, and

blackberries have regular battles with this pest.

As fruit crops begin to ripen across the state, one insect

pest is almost certain to cause problems, the green June

beetle. Unlike the Japanese beetle that is primarily a leaf

feeder, although it will attack damaged fruit and sound

fruit on occasion, the green June beetle almost exclusively

feeds on the fruit. It may be easier to list fruit that this pest

does not attack as most of the fruit crops are vulnerable.

Growers of peaches, apples, grapes, blueberries, and

blackberries have regular battles with this pest.

Green June beetle is attracted to ripening fruit often in the

last few days before maturity. This is when the sugar

content of the fruit begins to peak. Damage by green June

beetle often attracts other insect harvest pests including

sap beetle, Japanese beetles, fruit flies, wasps and bees.

Control of green June beetle is not easy. Although we have

very effective sprays that can eliminate the pest, the

difficulty is timing. They typically arrive in the last few

days before harvest begins. The required pre-harvest

interval (PHI) of the more effective sprays is longer than

period before harvest will begin, so they cannot be used

when the beetles arrive. Growers often will substitute a

less effective material with a short pre-harvest interval in

order to comply with the required waiting period.

Sanitation is also very important, not only for green June

beetle, but the other pests that are attracted to the

damaged fruit and the scent of the fermenting plant juices.

To the extent the practical and possible, the damaged fruit

needs to be removed from the orchard/vineyard. In

intense situations or where organic-certification precludes

the use of synthetic insecticides, netting can be used over

small plants and vines as a barrier to the beetles.

VEGETABLES

FUNGICIDE FAILURES IN COMMERCIAL VEGETABLE CROPS

By William Nesmith

When I started my professional career with commercial

vegetable producers 34 years ago, a long-standing,

successful Virginia vegetable grower told me this. "Teach

them that water is critical to vegetable production. In dry

seasons they need timely irrigation, but when Mother

Nature supplies it in wet seasons, they will need timely

fungicide sprays ahead of the rains." In my opinion, that

advice is as fitting today as it was in 1970.

The protracted periods of rainy weather this spring have

led to a number of serious disease outbreaks in

commercial vegetable crops. Even growers with much past

success are having serious problems in disease

management. On most new vegetable farms, the inoculum

load has been low previously, allowing some to escape

serious disease in recent years and get by with less than

good spray programs for a few years. Such, have not

learned earlier of the need to incorporate a strong disease

management program in their operation. At a recent field

day, I reminded the audience that one must always give

luck its due credit in assessing management issues - until a

disease is critical, the critical value of controlling it is not

visible! A poor spray program in situations of low disease

pressures can be adequate. Such luck can guide one to

decide that recommended spray programs are not as

important as others have advised, leading to inadequate

equipment, omitted or reduced sprays, and lack of needed

products in the supply system. Some experienced sages

have even been hurt by relying too heavily on newer

products and extending spray intervals rather a using

them in a rotational pattern with proven preventive

products and closer spray intervals. Long spray intervals

look real good to the bottom-line in dry weather, but some

are seeing a very different bottom line (in red) from those

same programs in this wet season.

Vine crops are especially hard hit on some farms from

outbreaks of anthracnose, gummy stem blight, Alternaria

leaf spots, and scab even before we enter the season for

Phytophthora blight, powdery mildews and downy

mildews. By the way, expect an earlier than normal season

for all three diseases and at much higher levels than

normal.

Although a number of other issues are involved, such as

site selection, rotation, and infested transplants, with the

operations I have reviewed, fungicide application

difficulties seem central to the problems. Some growers

just have not used much fungicide. Some were waiting to

see if the disease would become serious enough to warrant

spraying. Others have not used them often enough,

mainly relying on the schedules used in drier seasons then

trying to "chase" the outbreak rather than preventing it.

Some have been waiting for it to stop raining so they could

get into the field; those need to realize that heavy grass-

sod spray-strips have a place in our soils. Some have

abandoned wet areas of the field and left it unsprayed for

the pathogens to use as a staging area; those could have

helped themselves with either prompt destruction or some

spot spraying with back-pack equipment. Abandoning a

portion of the field is leaving it for the pest to colonize.

Others that apply a tank mixture of fungicides and

insecticides have been afraid to spray during the day time

for fear of killing their bees (a major concern) so they have

been waiting for dark, yet by late in the day and at dark

thunderstorms have moved in, often night after night.

Separate the fungicide and insecticide application in such

weather, because you need that fungicide on and dried

before the rain, with morning applications often being the

best options to insure drying for the wet event. Some have

selected the wrong fungicides for the problems present.

Fungicides are important tools for controlling infectious

diseases in commercial vegetable crops. Chemical

fungicides work mainly as preventives but some newer

eradicants (curatives) have moved into the system.

However, where curatives are available they need to be

used in a preventive manner, rather than always relying

on that curative potential, by either applying in a tank

mixture or a rotation pattern with other effective products.

Plan to control by inhibiting subsequent infections of the

pathogen rather than by curing the diseased plant, because

the pathogens have very short reproductive cycles and

build their numbers very rapidly, in a matter of days.

Application timing is very important relative to when the

infection and sporulation events are occurring in disease

development. For most fungicides, applications should be

made before the disease even begins, or no later than when

the first few lesions appear. Why? Because these materials

stop the pathogens by preventing spore germination and

preventing subsequent infections and not by

killing/eradication of the pathogen after it is already

inside the plant. Most infections occur while the leaf is wet,

so the fungicide needs to be on target tissue and dried

before the moisture event. Failure to appreciate this

concept has been central to most of the decision making in

problem fields that I have encountered. Yes, there is a lot

to do in a day, and it is difficult to find time to do it, but

disease prevention measures must take a higher priority in

some seasons than others. Wet seasons are disease

seasons!

Good spray coverage is a critical issue with fungicide use.

Protective fungicides should be applied to achieve good

coverage for the best protection under strong disease

pressure. Although some products are formulated to be

less sensitive to coverage issues than others, the goal for all

should be good coverage put in place and dried before the

wet events.

Spray adjuvants or surfactants should be used if the

product label recommends them to ensure uniform

coverage. Do not use these materials unless the label

indicates they are needed.

It is important to maintain proper application intervals

with fungicides, especially in wet weather. If it rains before

the material is dry on the foliage, most of the fungicide

will wash off. Yet infection occurs while the plants are

wet-when the protective chemical is most needed! If it

seems likely that the fungicide can remain on the foliage

for two hours or more before a rain, it is best to go ahead

and make an application. This is particularly true if the

spray interval has been long and/or a protracted weather

event is involved. In addition, regular applications are

needed to keep up with new plant growth and loss of the

applied material due to weathering. With the fast growth

rates experienced this season, it is not uncommon to have

one or two feet of new growth that has no fungicide

between applications. If inoculum is in the field, that

foliage has probably already become infected.

SHADE TREES AND ORNAMENTALS

PINE WILT NEMATODE ACTIVE IN KENTUCKY

By John Hartman

Scots and Austrian pines in Kentucky landscapes and

along highways are now showing symptoms of pine wilt

disease caused by the pine wood nematode

(Bursaphelenchus xylophilus). Although we see the disease

mainly on Scots pines, Austrian pines are also susceptible,

and on rare occasions white pines show the disease. In

some cases, the disease completes the demise of trees

already infected with pine tip blight disease.

Symptoms. The first visible symptom is discoloration of

needles from green to yellow to brown. These symptoms

are accompanied by a marked decrease in resin flow that is

apparent when a branch is cut and resin does not seep

readily from the wound. Wilt and death of affected trees

may occur gradually or very rapidly. Brown trees can be

seen now within groups of pines and they contrast

markedly with nearby heathy green trees. Trees infected

in the spring may wilt and die by late summer.

Spread. Long-horned cerambycid beetles carry the

nematodes on and in their bodies as they emerge from

infected (usually dead) trees. Beetles then migrate to

nearby pines where nematodes enter healthy shoots

through feeding wounds left by the beetles. They migrate

into resin canals where they rapidly multiply and cause

the pines to wilt and die. Dying pines are attractive to the

beetles for breeding; the cycle then repeats.

Sampling for diagnosis. Positive diagnosis of this disease

requires microscopic identification of the nematode. A

recently wilted or killed pine can be sampled by collecting

the portion of an affected branch closest to the trunk. A

good sample might consist of a branch section 1/2 inch or

more in diameter, and about a foot long. Alternatively,

samples consisting of sapwood can be taken from the

trunk or main branches using a hatchet or an increment

borer. It is best to collect several samples from various

parts of the tree. Put the wood samples in a plastic bag

and submit them to the Plant Disease Diagnostic Lab via

the County Extension Office.

Disease management. If pine wilt nematode disease is

confirmed in a planting of pines, remove and destroy the

affected trees. This measure will help prevent spread of

the disease to nearby healthy pines. Control of the insect

vector with insecticide treatments has not proven to be a

useful tool for managing pine wilt disease. Under unusual

experimental conditions, the pinewood nematode was

shown to move from fresh infected pine wood chips to

young Scots pines. Thus, it is probably a good idea to

compost fresh chips from pine wilt-infested trees for at

least one month before using them as mulch around

susceptible pine species.

Category

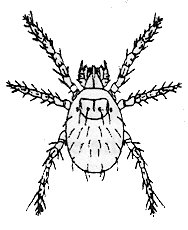

CHIGGERS- JUST SCRATCHING THE SURFACE

By Lee Townsend

Chigger bites, a sure sign of summer, can be the "souvenir"

of a blackberry-picking trip, working, or playing in

overgrown brushy or grassy areas. Chiggers usually feed

where clothing fits tightly against the skin - waistbands,

etc. Digestive juices used by the mites to dissolve skin cells

cause bite sites to become red and swollen. Later, angry

red welts will form that itch intensely for several days. As

if that were not enough, bite sites can become infected if

they are scratched incessantly.

Chigger bites, a sure sign of summer, can be the "souvenir"

of a blackberry-picking trip, working, or playing in

overgrown brushy or grassy areas. Chiggers usually feed

where clothing fits tightly against the skin - waistbands,

etc. Digestive juices used by the mites to dissolve skin cells

cause bite sites to become red and swollen. Later, angry

red welts will form that itch intensely for several days. As

if that were not enough, bite sites can become infected if

they are scratched incessantly.

Here are some ways to protect yourself-

Wear long pants tucked into boots or socks to keep

chiggers on the outside of your clothing Wear loose fitting

clothing and avoiding sitting or lying directly on the

ground.

Avoid walking through overgrown fields and brush,

especially from July through early September. Instead,

walk in the center of mowed trails to avoid vegetation

where chiggers (and ticks) congregate.

Use an insect/ tick repellent. Products containing diethyl

toluamide (DEET) or permethrin (clothing only) are most

effective. Be sure to read and follow directions for use on

the container. A hot, soapy shower immediately after

coming indoors will remove chiggers that have not yet

attached.

Chigger management

Control of chigger infestations in large yards, parks,

camps, picnic sites, and other recreational areas is often

impractical. However, chiggers in play and picnic areas

and around trails can be reduced by vegetation

management. Regular mowing and brush removal creates

a less favorable habitat for chiggers and the rodents and

other small animals on which they feed. This is the way to

a long-term solution.

Insecticide sprays may provide some temporary reduction

of chiggers. They are most effective when directed into

areas where chiggers and their animal hosts are likely to

frequent. Options include bifenthrin (Ortho Lawn Insect

Killer), carbaryl, (Sevin), cyfluthrin (Bayer Advanced Lawn

and Garden Multi-Insect Killer, and any of a number of

products containing permethrin. Be sure to read the

product label carefully to be sure the site you are planning

to treat is on the label. Also, look for specific instructions

for applications against chiggers that can increase control.

DIAGNOSTIC LAB HIGHLIGHTS

DIAGNOSTIC LAB - HIGHLIGHTS

By Julie Beale and Paul Bachi

Recent samples in the Diagnostic lab have included

stinkbug injury, zinc deficiency, and Fusarium stalk rot on

corn; black shank, blue mold, frogeye leaf spot; soreshin,

Fusarium basal stem canker, black root rot, Rhizoctonia

leaf blight, Fusarium wilt; tomato spotted wilt virus,

manganese toxicity, hollow stalk and weather fleck

(ozone) on tobacco.

On fruits and vegetables, we have diagnosed Fusicoccum

canker on blueberry; anthracnose, bitter rot, black rot and

potash deficiency on grape; bitter rot, cedar-apple rust,

fireblight, frogeye, Pythium root rot on apple; brown rot

on peach; Entomosporium leaf spot on pear; Blumeriella

leaf spot on cherry; anthracnose on walnut; anthracnose

and Rhizoctonia stem rot on bean; and Fusarium wilt,

early blight, bacterial speck and spot; Septoria leaf spot

and Cladosporium leaf mold on tomato.

On ornamentals and turf, we have seen southern blight on

hosta; Pythium root rot and manganese deficiency on

chrysanthemum; Rhizoctonia stem rot and Pythium root

rot on petunia; powdery mildew on dogwood; scab on

crabapple; Actinopelte leaf spot on oak; Phomopsis twig

blight on juniper; Verticillium wilt on smoketree;

Cercospora leaf spot on willow; and summer patch on turf.

IPM TRAP COUNTS:

By Patty Lucas, University of Kentucky Research Center

UKREC-Princeton, KY, July 2-9, 2004

| Black Cutworm

| 0

|

| True Armyworm

| 18

|

| Corn Earworm

| 21

|

| European Corn Borer

| 1

|

| Southwestern Corn Borer

| 27

|

|

To view previous trap counts for Fulton County, Kentucky

go to - http://ces.ca.uky.edu/fulton/anr/

and click on "Insect Trap Counts".

For information on trap counts in southern Illinois visit the

Hines Report at -

http://www.ipm.uiuc.edu/pubs/hines_report/index.html.

The Hines Report is posted weekly by Ron Hines, Senior

Research Specialist, at the University of Illinois Dixon

Springs Agricultural Center

MISCELLANEOUS

LARGE "BUGS OF SUMMER"

By Lee Townsend

Several of Kentucky's largest or most unusual insects will

be active over the next few weeks. A few species that are

most likely to appear and at least arouse curiosity are:

The eastern Hercules beetle (Dynastes tityus) has a large

(2" to 2-1/2" long) greenish-gray to black body. Males have

a large distinctive horn on the head and are sometimes

called rhinoceros beetles. The adults are attracted to lights

during mid- to late summer. The larvae are large white

grubs that feed in the center of decaying logs and stumps.

It is the largest beetle in Kentucky and is harmless. These

beetles occur throughout the southeastern United States.

The eastern Hercules beetle (Dynastes tityus) has a large

(2" to 2-1/2" long) greenish-gray to black body. Males have

a large distinctive horn on the head and are sometimes

called rhinoceros beetles. The adults are attracted to lights

during mid- to late summer. The larvae are large white

grubs that feed in the center of decaying logs and stumps.

It is the largest beetle in Kentucky and is harmless. These

beetles occur throughout the southeastern United States.

Dobsonflies are large, prehistoric-looking insects. They

have soft gray bodies and two pair of wings with a

network of veins. These fluttery-flying insects are usually

found near creeks or streams. The male has an impressive

pair of long, slender mouthparts. Females have the same

body shape but very small mouthparts.

Dobsonflies are large, prehistoric-looking insects. They

have soft gray bodies and two pair of wings with a

network of veins. These fluttery-flying insects are usually

found near creeks or streams. The male has an impressive

pair of long, slender mouthparts. Females have the same

body shape but very small mouthparts.

The female dobsonflies lay their eggs on overhanging

branches or structures over streams. The larvae called

"hellgrammites" usually occur under stone in streams

where they feed on insects that live in the water. The

larvae live for several years in the water and are used as

bait by fishermen. The adults only live a few days to

reproduce, then die.

- Giant water bugs have a variety of common manes as

"toe biters", "fish killers", and "electric-light bugs". They are

large (about 2.5 inches long) with flat, brown, oval bodies,

large eyes and a pair of grabbing front legs. These insects

are good fliers and can show up as uninvited guests in

swimming pools. These water bugs live in quiet standing

water of ponds, lakes, and stream pools, where they feed

on aquatic insects, snails, tadpoles, and even minnows.

While not dangerous, they can inflict painful bite if

handled.

- The European hornet, about 1.5 inches long, is an

impressive and fearsome-looking insect. It is brown with

yellow markings, particularly at the end of the abdomen.

European hornets generally nest in cavities in trees or

other protected sites. They will fly at night and are

attracted to lights. More information is available in Entfact

600 - The European Hornet in Kentucky.

http://www.uky.edu/Agriculture/Entomology/entfacts/struct/ef600.htm

The cicada killer wasp (about 2 inches long) can be seen

cruising over grassy areas during July and August. They

are black with yellow markings and rusty-colored wings.

These wasps burrow into sandy or well-drained soil with

sparse grass color. They live in individual burrows but

where conditions are right, large groups can build up over

time. They are curious but not aggressive. The females can

sting and will if handled but do not respond like

yellowjackets or other common social wasps.

The cicada killer wasp (about 2 inches long) can be seen

cruising over grassy areas during July and August. They

are black with yellow markings and rusty-colored wings.

These wasps burrow into sandy or well-drained soil with

sparse grass color. They live in individual burrows but

where conditions are right, large groups can build up over

time. They are curious but not aggressive. The females can

sting and will if handled but do not respond like

yellowjackets or other common social wasps.

NOTE: Trade names are used to simplify the information presented in

this newsletter. No endorsement by the Cooperative Extension Service

is intended, nor is criticism implied of similar products that are not

named.

Lee Townsend

Extension Entomologist

BACK

TO KY PEST NEWS HOME

Many corn fields experienced long periods of wet soils

after planting. When soils are generally wet to saturated

early in the season, the corn plant produces a shallower

root system than in seasons when periods of drying take

place. Compounding this situation is the fact that root rots

have been diagnosed in a number of instances in Kentucky

corn fields, principally root rot caused by the fungus

Fusarium verticillioides (formally known as Fusarium

moniliforme, the same fungus that can produce fumonisins

in the grain). Root rot caused by F. verticillioides is

typically triggered by some stress to the plant, including

herbicide injuries. Pythium root rot is favored by soil

saturation, so fields with poor drainage (either poor

surface drainage or poor internal soil drainage) are prone

to this problem.

Many corn fields experienced long periods of wet soils

after planting. When soils are generally wet to saturated

early in the season, the corn plant produces a shallower

root system than in seasons when periods of drying take

place. Compounding this situation is the fact that root rots

have been diagnosed in a number of instances in Kentucky

corn fields, principally root rot caused by the fungus

Fusarium verticillioides (formally known as Fusarium

moniliforme, the same fungus that can produce fumonisins

in the grain). Root rot caused by F. verticillioides is

typically triggered by some stress to the plant, including

herbicide injuries. Pythium root rot is favored by soil

saturation, so fields with poor drainage (either poor

surface drainage or poor internal soil drainage) are prone

to this problem.

As fruit crops begin to ripen across the state, one insect

pest is almost certain to cause problems, the green June

beetle. Unlike the Japanese beetle that is primarily a leaf

feeder, although it will attack damaged fruit and sound

fruit on occasion, the green June beetle almost exclusively

feeds on the fruit. It may be easier to list fruit that this pest

does not attack as most of the fruit crops are vulnerable.

Growers of peaches, apples, grapes, blueberries, and

blackberries have regular battles with this pest.

As fruit crops begin to ripen across the state, one insect

pest is almost certain to cause problems, the green June

beetle. Unlike the Japanese beetle that is primarily a leaf

feeder, although it will attack damaged fruit and sound

fruit on occasion, the green June beetle almost exclusively

feeds on the fruit. It may be easier to list fruit that this pest

does not attack as most of the fruit crops are vulnerable.

Growers of peaches, apples, grapes, blueberries, and

blackberries have regular battles with this pest.

Chigger bites, a sure sign of summer, can be the "souvenir"

of a blackberry-picking trip, working, or playing in

overgrown brushy or grassy areas. Chiggers usually feed

where clothing fits tightly against the skin - waistbands,

etc. Digestive juices used by the mites to dissolve skin cells

cause bite sites to become red and swollen. Later, angry

red welts will form that itch intensely for several days. As

if that were not enough, bite sites can become infected if

they are scratched incessantly.

Chigger bites, a sure sign of summer, can be the "souvenir"

of a blackberry-picking trip, working, or playing in

overgrown brushy or grassy areas. Chiggers usually feed

where clothing fits tightly against the skin - waistbands,

etc. Digestive juices used by the mites to dissolve skin cells

cause bite sites to become red and swollen. Later, angry

red welts will form that itch intensely for several days. As

if that were not enough, bite sites can become infected if

they are scratched incessantly.

The eastern Hercules beetle (Dynastes tityus) has a large

(2" to 2-1/2" long) greenish-gray to black body. Males have

a large distinctive horn on the head and are sometimes

called rhinoceros beetles. The adults are attracted to lights

during mid- to late summer. The larvae are large white

grubs that feed in the center of decaying logs and stumps.

It is the largest beetle in Kentucky and is harmless. These

beetles occur throughout the southeastern United States.

The eastern Hercules beetle (Dynastes tityus) has a large

(2" to 2-1/2" long) greenish-gray to black body. Males have

a large distinctive horn on the head and are sometimes

called rhinoceros beetles. The adults are attracted to lights

during mid- to late summer. The larvae are large white

grubs that feed in the center of decaying logs and stumps.

It is the largest beetle in Kentucky and is harmless. These

beetles occur throughout the southeastern United States.

Dobsonflies are large, prehistoric-looking insects. They

have soft gray bodies and two pair of wings with a

network of veins. These fluttery-flying insects are usually

found near creeks or streams. The male has an impressive

pair of long, slender mouthparts. Females have the same

body shape but very small mouthparts.

Dobsonflies are large, prehistoric-looking insects. They

have soft gray bodies and two pair of wings with a

network of veins. These fluttery-flying insects are usually

found near creeks or streams. The male has an impressive

pair of long, slender mouthparts. Females have the same

body shape but very small mouthparts.

The cicada killer wasp (about 2 inches long) can be seen

cruising over grassy areas during July and August. They

are black with yellow markings and rusty-colored wings.

These wasps burrow into sandy or well-drained soil with

sparse grass color. They live in individual burrows but

where conditions are right, large groups can build up over

time. They are curious but not aggressive. The females can

sting and will if handled but do not respond like

yellowjackets or other common social wasps.

The cicada killer wasp (about 2 inches long) can be seen

cruising over grassy areas during July and August. They

are black with yellow markings and rusty-colored wings.

These wasps burrow into sandy or well-drained soil with

sparse grass color. They live in individual burrows but

where conditions are right, large groups can build up over

time. They are curious but not aggressive. The females can

sting and will if handled but do not respond like

yellowjackets or other common social wasps.