Subdivisions of the Lexington and Perryville (McFarlan, 1938c.)

HIGH BRIDGE (Campbell, 1898).—Massive, cliff-forming limestone of Chazy and Stones River age. Three formations are recognized:1

Camp Nelson (Miller, 1905).—Limestone composed of irregular patches and ramifications of granular rock of the Oregon type, interpreted as branching fucoids and presumably algal in origin, distributed through a matrix of dense limestone of the Tyrone type. On weathering the surface becomes honeycombed. Fossils are not common. The more characteristic are Maclurites bigsbyi, Escharopora ramosa, Rhinidictya trentonensis, and various cephalopods. Thickness, about 300 feet exposed above drainage.

Oregon.—"Kentucky River Marble" (Miller, 1905).—Grey to cream and buff-colored, granular, magnesian limestone. It is barren of fossils. Thickness, 15 to 35 feet.

Tyrone.—"Birdseye limestone" of Linney (Miller, 1905).—Dense, grey, dove, or cream-colored limestone, breaking with conchoidal fracture, and with small facets of coarsely crystalline calcite. On weathering the surface becomes white, in which the darker facets are conspicuous, giving rise to the name Birdseye. A bed of bentonite, a greenish clay, occurs 15 to 25 feet below the top. This is a consistent horizon marker in deep drilling in the state. (Pencil Cave of southern and western Kentucky. In the eastern part of the state the term is used for a shale break between the Glen Dean and lower Chester.)

The above mentioned bentonite, which is the principal and most consistently developed bed, was first recognized by Ulrich (1888). It ranges in thickness from a few inches to 5 feet.

Two others are known:2

(a) A bentonitic shale has been observed in several localities at the Tyrone-Curdsville contact. At Curdsville Station (abandoned) on the Cincinnati-Southern Railroad in northern Mercer County, it is about 2 feet thick and more coarsely textured than the lower layer. Abundant flakes of biotite are conspicuous. Elsewhere the Curdsville is in contact with the Tyrone, and in places the two are firmly cemented together. This cemented disconformity has been regarded as rather unique. On the basis of position in the section, as well as appearance, it seems to be the same as the ash layer mentioned by Butts (1926) from Birmingham, Alabama, and is Born's (1939) "Mud Cave" of the Cumberland River oil field.

(b) A third and thin seam has been recognized by Young (1940) 10 feet above the base of the Tyrone. It attains a thickness of 1 foot.

All three bentonite layers have been observed in the Tennessee Ordovician (Charles Wilson, personal communication).

The recognition of the "Mud Cave" at the top of the Carters limestone and the "Pencil Cave" within it in Clay County, Tennessee (Born, 1939) in a section where the Tyrone is "absent" would indicate that the upper Carters here is the equivalent of the Tyrone elsewhere. These are the two main bentonite layers of the Kentucky Ordovician mentioned above.

When first known, these bentonites (or metabentonites) seemed to offer a widespread means of precise stratigraphic correlation. The usefulness, though, has somewhat decreased with the increasing number of such layers known. (See Rosenkrans, 1933, 1934, 1936; Whitcomb and Rosenkrans, 1935; Kay, 1929, 1931, 1935; Smith, 1931; Ulrich, 1888; and Stose and Jonas, 1927.) In the Appalachian Valley, New York, and Ontario they have been described from the Chazy, Black River, and Trenton. At least twelve are known in the Ordovician of Pennsylvania. The greatest thickness reported is 96 inches in the lower Martinsburg of southwestern Virginia. The tie-up between these and the Kentucky bentonites has not yet been well established.

Fossils are few and include such forms as Strophomena incurvata, Orthis tricenaria, Rhinidictya nicholsoni, Phyllodictya frondosa, Escharopora ramosa, Leperditia fabulites, Tetradium cellulosum, and the cephalopods Endoceras, Actinoceras, and Cameroceras.

The Leray limestone is recognized in New York as the uppermost member of the Lowville. It is present at least locally in Kentucky at the top of the Tyrone and is characterized by an assemblage of molluscs including species of Ctenodonta, Lophospira, Omospira, Oxydiscus and others (Bassler, 1932).

Decorah Shale.—Bassler (1932) in his geological section at High Bridge, Kentucky, lists the Decorah as a locally-developed thin bed of clay.

TRENTON

LEXINGTON LIMESTONE (Campbell, 1898).—As originally defined by Campbell the Lexington limestone included beds intervening between the Tyrone (Lowville) and his Flanagan chert. In later use by Foerste and Miller it came to include all beds between the Tyrone and Cynthiana. Along with the latter it comprises the Trenton of Kentucky. A number of formations have been recognized.

The divisions are in part faunal units and in part lithologic. They have been described in some detail by Miller and Foerste and more recently by the writer (1931b). The general lithology is that of thin- to medium-bedded grey crystalline limestone and shale. The Brannon with its distinctive lithology, a contorted and "concretionary-like" siliceous limestone yielding a residuum of chert on weathering, has usually been designated as the mid-Lexington. It corresponds with the lower part of Campbell's Flanagan chert. In his type area the Perryville is not present in the section. The same writer called attention to the absence of the Flanagan chert in the region south of the Kentucky River fault, and his observation was in the main correct.

|

|

Subdivisions of the Lexington and Perryville (McFarlan, 1938c.) |

The Perryville is better used as a distinct unit rather than a part of the Lexington (McFarlan, 1938c). This separation is justified by unconformity in spite of close faunal relationship. At the well-known Old Crow Distillery section near Frankfort it rests on Woodburn in apparent conformity. Near Danville in Boyle County, and south of Burdett Knob in Garrard County in the southern Bluegrass, it rests on the Benson.

Curdsville (Miller, 1905).-Coarsely crystalline medium- to heavy-bedded grey limestone with much chert. There is locally a basal breccia with Tyrone fragments incorporated in a Curdsville matrix. Characteristic fossils include Orthis tricenaria,3 Dinorthis pectinella,3 Rhyncholrema subtrigonale, Streplelasma profundum3 and Sowerbyella curdsvillensis. The Curdsville fauna is now recognized in the basal Hermitage of central Tennessee (Charles Wilson, unpublished). Thickness, about 20 feet.

Hermitage (Hayes and Ulrich, 1903).-A more or less siliceous and crystalline limestone formerly known as the Logana (Miller, 1905). Dalmanella bassleri and Prasopora falesi are common, and Heterorthis clytie is regarded as characteristic but is not common. The formation is not readily distinguished from the Jessamine on either fauna or lithology. Near the top there is commonly a molluscan horizon where Modiolodon oviformis, Sinuites obesus, S. pervolutus, and Lophospira obliqua are abundant. Thickness, 30 to 35 feet.

|

FIG. 3. Map and sections showing

unconformable relationships of |

Jessamine (Miller, 1919,—replacing the name of Wilmore (Nickles, 1905)).—This is the zone of abundant and typical Prasopora simulatrix (also P. falesi) together with Dalmanella bassleri, Rhinidictya neglecta, Liospira americana, and Hebertella frankfortensis. Over much of Jessamine and Fayette counties, at least, the top of the formation is marked by a hard fine-grained limestone containing a profusion of Lophospira and other molluscs. Sowerbyella rugosus occurs in the lower part of the formation and again in the uppermost beds. In the southern Blue Grass the upper hard beds contain an abundance of ostracods, principally Ceratopsis. Thickness, 75 to 80 feet.

The Jessamine is not recognized in the Trenton of central Tennessee but is probably represented there by the upper Hermitage.

Benson (Foerste, 1913 and 1913a).—The association of Rhynchotrema increbescens and Hebertella frankfortensis in abundance is more or less characteristic, though both occur lower in the section. The uppermost beds are characterized by the additional occurrence of Stromatocerium pustulosum, Dinorthis ulrichi, Strophomena vicina, and Cyphotrypa frankfortensis. Associated with the Stromatocerium reef, and as diagnostic, is a reef composed of the contorted laminae of an undescribed species of Ceramoporella. It occurs usually a few feet above the Stromatocerium horizon and is not known in the recurrent upper Benson fauna of the Cornishville.

| PLATE III | |

|

|

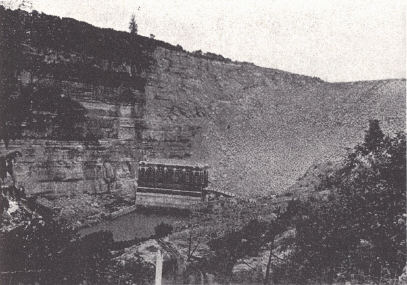

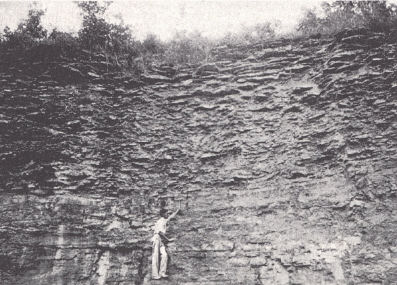

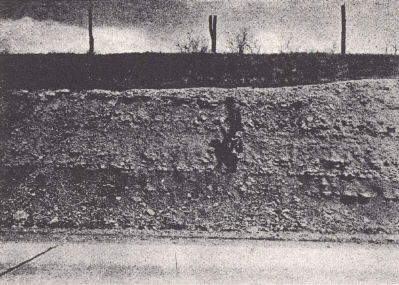

| FIG. 1. High Bridge limestone at Dix River Dam, near Burgin, Mercer County. Some difficulty was encountered in the beginning with leakage by way of solution channels in the limestone. These were plugged by means of asphalt forced in drilled holes above the dam. | FIG. 2. Brannon limestone at Brannon Station on the Southern Railroad, Jessamine County, showing the irregular bedding and bouldery character of the fine-grained siliceous limestone. |

|

|

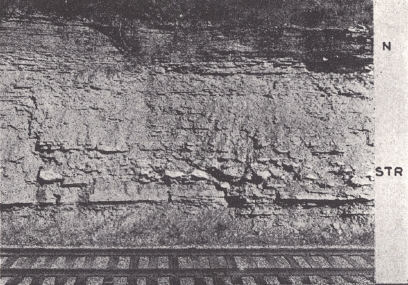

| FIG. 3. Bentonitic clay at the Tyrone-Curdsville contact. Southern Railroad cut about 2 miles south of High Bridge, Mercer County. This is a widespread stratum occurring at a disconformable contact. It is the same contact described by Miller (1919) as locally cemented, with no tendency of the rock to cleave along the line of contact. | FIG. 4. The basal Cynthiana represented by the Crepipora spatiosa zone (Sulphur Well member) rests disconformably on the upper Benson. The characteristic Stromatocerium pustulosum zone is well developed at the level of the hammer. Formations missing are the Brannon, Woodburn, and Perryville. Locality about 2 miles south of Ambrose (Sulphur Well), Jessamine County. |

Two to 4 feet of even-bedded Brannon-like limestone, 15 to 20 feet below the top of the Benson, forms a recognizable member over southern Jessamine and Fayette, and northern Garrard counties. This limestone yields a zone of residual chert similar to that of the Brannon. It can easily be confused with the latter but underlies the Stromatocerium-Ceramoporella horizon.

Thickness, 40 to 75 feet.

Brannon (Miller, 1913).—A fine-grained siliceous bouldery or "concretionary" limestone with much shale in the lower part. On weathering, it gives rise to a conspicuous zone of chert drift and forms the lower part of Campbell's (1898) Flanagan chert. Fossils are not common except in shaly zones. The Brannon is the horizon where the sponges Brachiospongia digitata and Pattersonia aurita have been found. The writer has found P. aurita in the top of the Benson. Of interest is the early occurrence of Eridotrypa briareus. The bouldery structure seems to be frequently a "mud flow" structure; at other places, an involved cross-bedding. Thickness, 15 to 20 feet.

Woodburn (Miller, 1913).—A crystalline limestone with unusually high phosphorus content. The most useful fossils are Columnaria halli and C. alveolata var., associated with Platystrophia colbiensis, Constellaria teres (locally abundant), Cyclora minuta, and Rhynchotrema increbescens. Thickness, about 40 feet.

The complete section of the Lexington limestone is developed only in the Lexington-Frankfort region. To the north and south there is progressive elimination of the upper beds. Where it goes under cover in the southern Blue Grass, the mid-Benson forms the top; in northern Kentucky, the Jessamine. (See fig. 3.) Whether this means late Lexington or post-Lexington uplift to the north and south is not known.

PERRYVILLE (Nickles, 1905).—The Perryville, as already indicated, rests unconformably on the Lexington and in turn is unconformably overlain by the Cynthiana. It has its best development on the western and southern flanks of the Jessamine dome. Here there are two distinct areas (fig. 3). Throughout, the southern area all three members are developed. In the northern area the Cornishville is not present, and Miller (1914, 1919, and 1925) has found the Faulconer "underlapping" the Salvisa to some extent, extending thus somewhat higher up the Arch.

In the region of maximum development in Boyle and Lincoln counties and vicinity, a thickness of about 40 feet is attained, of which not more than 6 to 8 feet is Cornishville. The maximum known thickness of Faulconer is 20 feet and the Salvisa 15 feet.

Faulconer (Foerste, 1912).—A porous coarsely crystalline light grey massive limestone, in its typical development a crowded mass of gastropod shells, chiefly Bellerophon troosti, Oxydiscus subaeutus, and Lophospira medialis. Silicification of this bed in weathering gives rise to the third conspicuous chert horizon of the Trenton, a fossiliferous chert.

Salvisa (Miller, 1913—the upper Birdseye limestone of Linney).—A compact limestone suggesting the Tyrone, including some of dark grey-black color. Characteristic fossils are Isochilina jonesi, Leperditia (several species), and Orthorhynchula linneyi. Locally it is softer and more argillaceous. Isochilina occurs more abundantly in this type of rock.

Cornishville (Foerste, 1912).—Crystalline fossiliferous grey limestone characterized by the recurrence of the upper Benson fauna. It is restricted to the counties of the southern Blue Grass.

Along the crest of the Arch and to the east two narrow isolated occurrences of Perryville are known, both along the West Hickman fault zone: (a) northern Jessamine County, and (b) two miles north and east of Paris. The Jessamine County occurrence involves both Faulconer and Salvisa and occurs in a graben and the bordering upthrow to the east where the beds dip in toward the down-faulted block. The Paris occurrence involves only Salvisa and is on the downthrow side of a single fault. This local preservation of Perryville between the Woodburn and Cynthiana in a structurally low position may indicate the initiation of this fault zone in the Mid-Ordovician.

An exposure approximately one-half mile south of the Ash Grove Pike in northern Jessamine County seems to indicate that the Faulconer and Salvisa are not entirely distinct stratigraphic units, but lithologic facies, in part contemporary. At this place 17½ feet of Faulconer underly the Cynthiana. The thickness exceeds slightly the combined thickness of the two a mile to the north. Eight feet above the base 2 feet of rock occur, Salvisa-like in appearance, and containing numerous specimens of Orthorhynchula linneyi, which is rather characteristic of that member. Certainly in the southern area around Danville, where the Salvisa has its best development, the Faulconer is not so well developed as farther north.

Another exposure having a bearing on this point is a small quarry at Braxton, a mile and a half southwest of Mundy's Landing in northern Mercer County. Here a breccia or intraformational conglomerate occurs in the upper 2 feet of the exposed Faulconer. The matrix is coarsely crystalline limestone, while the fragments are of “Salvisa” rock. Apparently the deposition of "dove" limestone had already begun in the Faulconer.

As to the general absence of Perryville over much of the Blue Grass, it is not certain whether this is to be interpreted as non-deposition or pre-Cynthiana removal.

CYNTHIANA (Foerste, 1906).—Fossiliferous limestone and shale. The unconformity at the base of the Cynthiana is a marked one and involves variation in the basal Cynthiana as well as the upper Lexington. In different places the Cynthiana rests on all formations from the Cornishville to Jessamine. The variation in thickness from 38 to 125 feet is primarily a matter of elimination of lower beds in a basal overlap onto a central area involving western Fayette, northern Jessamine, Franklin and Owen counties. The Cynthiana of the well-known Old Crow Distillery section in northern Woodford County and the section in the vicinity of Lexington include only the upper half and less of the section found elsewhere.

A number of attempts have been made to subdivide the Cynthiana. The relationships of these divisions as recently revised (McFarlan, 1938c) are given in figure 4. The divisions are more or less lenticular lithologic units with corresponding differences in fauna, and the upper and lower boundaries are not at the same stratigraphic level over wide areas.

Greendale (Foerste, 1906).—The name is from a railroad cut near Greendale Station on the Southern Railroad a few miles north of Lexington. There has been little precision in its use. It has in general been used for the rather fossiliferous crystalline limestones and shales typically shown in the Old Crow Distillery section and exposures around Lexington. The fauna includes such forms as Cyclonema varicosum, Eridotrypa briareus, E. aedilis, Orthorhynchula linneyi, Hebertella occidentalis, H. sinuata, H. subjugata, Constellaria emaciata, C. florida, C. fischeri, Dekayella foliacea,4 Escharopora falciformis, E. maculata, Rafinesquina winchesterensis, R. alternata and Platystrophia colbiensis.

At the type locality the upper 10 feet of the 15 feet exposed is more or less massive limestone of the Nicholas type and is regarded as belonging to that member. (See below.) Five feet of thinner bedded limestones and shales are exposed below. As commonly used, it included the fossiliferous layers below the Nicholas, and where the latter was not developed, it included the equivalent thinner bedded limestones and shales. The usage is thus not in keeping with the type exposure.

|

| FIG. 4. Correlation of the

named divisions of the Cynthiana formation showing basal overlap (MacFarlan, 1938c). |

Beds older than the Greendale of the Lexington-Frankfort region are well developed in the southern and southwestern Blue Grass along the outer margin of the belt of Cynthiana outcrop. They are equivalent in age to the lower Millersburg (Allonychia zone, etc.) and are characterized by a bryozoan assemblage including Crepipora spatiosa, Batostoma minnesotense, B. winchelli, a large species of Prasopora and Cyphotrypa, both undescribed, associated with an abundance of Eridotrypa aedilis and Peronopora milleri. This Crepipora zone is distinctive and widespread. For these beds, referred to above as pre-Greendale, the name Sulphur Well member is proposed from exposures along the Kentucky River fault in that vicinity in southeastern Jessamine County.

Millersburg (Foerste, 1914a).—The name was proposed for richly fossiliferous argillaceous rubbly limestone beginning with a lower zone rich in Allonychia flanaganensis and limited above by the Nicholas limestone. It is developed on the eastern side of the Arch and has been regarded as a more fossiliferous equivalent of the Greendale. More recent work has indicated, though, that the lower part of the Millersburg is pre-Greendale in age, only the upper part correlating with that member. Many precursors of Fairmount species are developed.

Nicholas limestone (Foerste, 1909a).—This is a comparatively heavy bedded medium- to coarse-grained limestone overlying the Millersburg in Nicholas County and vicinity. It is the quarry rock of that region and is overlain by the Rogers Gap. It is the equivalent of the quarry rock at Cynthiana and the River Quarry beds at Cincinnati. Similar beds are developed near Lexington and in Franklin County beneath the Rogers Gap. This phase, though widespread, is not persistent throughout the area of outcrop and, where not developed, the thinner limestones and shales have been referred to as Greendale or Millersburg. As indicated above, the exposed section at Greendale Station is mainly this Nicholas rock.

Rogers Gap (Foerste, 1912,1914a) .—Thin- to medium-bedded fossiliferous crystalline limestones and shales. It is the most consistently developed division of the Cynthiana and is known throughout the area of Cynthiana-Eden outcrop in Kentucky. At Carlisle (Nicholas County) and near Gratz (Owen and Henry counties) these beds consist of barren shales with intercalated fine-grained siliceous limestones. Eridorthis nicklesi, Clitambonites rogersensis, Leptaena gibbosa var. invenusta associated with Eridotrypa aedilis and a limited number of Merocrinus stem plates are characteristic. Hallopora onealli and also the varieties sigillaroides and communis are often present in limited numbers in the central and southern counties and are locally even more common. The characteristic assemblage, other than the forms mentioned, includes:

| Dalmanella multisecta D. emacerata Sowerbyella rugosus Platystrophia colbiensis |

Arthropora cleavelandi Escharopora acuminata E. falciformis Rhinidictya parallela |

| Bellerophon rogersensis Cyclonema varicosum Fusispira sulcata Lophospira bicincta |

Bollia unguloidea Ceratopsis chambersi Primitia centralis Ulrichia nodosa |

While given in the literature as post-Greendale in age, it underlies the Greendale at Butler (Pendleton County) and at Clay's Ferry in northern Madison County (fig. 4). At Cynthiana these beds underlie the well-developed Nicholas limestone. A conspicuous feature is the development of beds with a "bouldery" or "mud flow" structure. Similar beds in Owen County, though, are apparently higher in the section and more or less of Greendale age.

Gratz (Ulrich—undescribed in the literature).—This is a more or less barren shale and fine-grained impure limestone succession overlying the fossiliferous "Bromley" of Owen County (see above). It has been shown (McFarlan and Freeman, 1935) that the upper part of this zone is Rogers Gap and the rest a barren phase of the "Bromley."

EDEN

EDEN (Orton, 1873).—A series of blue shales and interbedded, fossiliferous limestones in its typical development.

At Cincinnati four members are recognized:

Fulton (Foerste, 1905).—Shales and fossiliferous limestones characterized by Merocrinus curtus, Eridorthis nicklesi, Sowerbyella plicatellus, Leptobolis insignis, Primitiella unicornis, and Triarthrus becki. Bassler (1932) regarded the Fulton as the overlapping south-westward extension of a phase of the Utica shale of New York. The fauna is much like that of the Rogers Gap except in the characteristic development of Hallopora onealli and the abundance of Merocrinus stem plates. The latter are particularly useful in the recognition of the Fulton and it may be referred to as the Merocrinus zone.

A maximum known thickness of 22 feet is found in the vicinity of Butler, Pendleton County.

Economy (Bassler, 1906).—The Aspidopora newberryi zone of Nickles, consisting of interbedded shales and fossiliferous limestone. Characteristic elements of the fauna include Coeloclema commune, Crepipora venusta, Amplexopora petasiformis, Monotrypa subglobosa, Hemiphragma whitfieldi, and several species of Aspidopora (Bassler, 1903, 1932). Thickness, 50 to 60 feet.

Southgate (Bassler, 1906).—Similar lithologically to the Economy. This is the zone of Batostoma jamesi, Ctenobolbina ciliata, and Aspidopora eccentrica. Cumings and Galloway (Tanner's Creek section, 1913) regarded Climacograptus typicalis and Bythocypris cylindrica as characteristic. Thickness, about 120 feet.

McMicken (Bassler, 1906).—The zone of Dekayella ulrichi of Nickles. Limestone is a more conspicuous element than in the lower members. The typical fauna includes D. ulrichi, and Coeloclema alternatum in great abundance, along with Batostoma jamesi and B. implicatum, Thickness, about 60 feet.

The Eden is the zone of Hallopora onealli, which is just as characteristic as Eridotrypa aedilis and E. briareus are of the Trenton. The larger varieties, communis and sigillaroides, of Hallopora onealli are more characteristic of the upper Eden. H. onealli does occur in limited numbers, associated with Eridotrypa aedilis in the Rogers Gap in central Kentucky, and Eridotrypa aedilis has more recently been identified in considerable numbers in the Fulton (McFarlan and Freeman, 1935) in the same region.

The divisions given above are those recognized at Cincinnati. Here the Fulton marks the introduction of Hallopora onealli and the contact with the Eridotrypa zone is sharp. In the southern Blue Grass the Fulton is not so readily differentiated from the underlying Rogers Gap. There is an association of Eridotrypa and Hallopora. Main reliance is placed on a well-marked Merocrinus zone (Fulton), in which this species occurs in profusion. It is present but not abundantly so in the Rogers Gap. Recent work (McFarlan and Freeman, 1935) has shown this member of the Eden to be present throughout the area of outcrop with the exception of an area involving parts of Bourbon, Harrison, and Scott counties.

In central Kentucky divisions recognized include the Fulton, Million (Nickles, 1905), and the Paint Lick (Foerste, 1909f). The latter constitutes the lower and massive part of the Garrard sandstone of Campbell (1898) and is quite barren of fossils. The Million has a thickness of 100 feet or more; the Garrard 50 to 80 feet, of which about two-thirds is Eden.

The Fulton here is the same well-marked Merocrinus zone, immediately above which Sowerbyella rugosus occurs in great profusion. This is a well-marked, easily recognized horizon. This species continues in abundance through the lower Eden, and is succeeded above by Dalmanella multisecta as the dominant brachiopod. Sowerbyella rugosus occurs also in the Fulton and Rogers Gap in considerable numbers. Where the Garrard is developed, it rests on this Sowerbyella zone and replaces the Dalmanella zone of the western and northern Blue Grass.

The central Kentucky members have not been accurately correlated with the Cincinnati divisions. West of Frankfort at the Shelby County line the lower Eden above the Fulton is represented by a zone containing H. onealli, Crepipora venusta, Coeloclema commune, Sowerbyella rugosus, Dalmanella multisecta, D. emacerata, and Cryptolithus tessellatus. With this rather typical Economy assemblage Dekayella ulrichi (or relative) and H. onealli var. sigillaroides occur in abundance. The assemblage is unusual for either Economy or basal Million.

The W. B. Perkins No. 11 well in Hart County is of interest as the log and samples do not show this shale zone above the Trenton; nor is it shown in logs for Cumberland County and vicinity of southern Kentucky.

There has been some difference in opinion as to the equivalent of the Eden in the New York section. (See Cumings, 1922; Ulrich and Schuchert, 1902; Ulrich, 1904, 1911; Bassler, 1915; Raymond, 1916; and Foerste, 1916.) It is usually regarded as equivalent to the Utica and Frankfort shales of New York and is represented in the upper Martinsburg of the Appalachians.

MAYSVILLE

FAIR VIEW (Bassler, 1906).—This is the Plectorthis plicatella zone of Cumings and Galloway (1913). It includes Nickles' (1902) Mt. Hope or Amplexopora septosa beds and his Fairmount or Dekayia aspera beds. The faunal change from the McMicken is not abrupt. Common forms are Plectorthis plicatella, Platystrophia laticosta, Amplexopora septosa, Batostoma implicatum, Dekayia aspera, Escharopora falciformis, E. pavonia, Hallopora andrewsi, H. dalei, Heterotrypa subfrondosa, Homotrypa curvata, Constellaria florida, and Peronopora vera.

Mt. Hope (Nickles, 1902).—Thin-bedded fossiliferous limestone and shale. It overlies the Dekayella ulrichi zone of the Eden and is characterized by the introduction of Platystrophia, Constellaria florida, Zygospira cincinnatiensis, Hallopora dalei, and many other bryozoa. Plectorthis neglecta is regarded as characteristic. In central Kentucky this horizon is represented in the upper Garrard. Strophomena maysvillensis occurs in moderate numbers. Locally, in the Cincinnati region the base is characterized by a massive limestone crowded with Dalmanella multisecta. Thickness, 40 to 50 feet.

Fairmount (Nickles, 1902).—Fossiliferous limestones and shale constituting the "Hill Quarry beds" of Cincinnati and vicinity. Here the Fairmount is marked at its base by the Strophomena planoconvexa zone, a restricted horizon of about 5 feet where this species occurs in great numbers. The occurrence of several species of Plectorthis—P. plicatella, P. fissicosta, and P. aequivalvis—associated with Constellaria florida, Hallopora dalei, and Platystrophia laticosta is characteristic. In the central and southern Blue Grass the fauna is referred to by Foerste (1912) as the Maury phase. The rock is often a rubbly limestone. The base is marked by a profusion of Strophomena maysvillensis and Constellaria florida. Other characteristic forms are Orthorhynchula linneyi (upper Fairmount), Escharopora hilli, Platystrophia ponderosa (lowest occurrence), Hallopora dalei, and Monticulipora mammulata. The topmost beds of the Garrard sandstone contain Strophomena maysvillensis in abundance, thus placing them in the basal Fairmount. Thickness, about 50 feet at Cincinnati and 75 feet in the southern Blue Grass.

MCMILLAN (Bassler, 1906).—This group includes the Bellevue, Corryville, and Mt. Auburn formations as exposed in the region around Cincinnati. In the southern Blue Grass the Tate, Gilbert, and Mt. Auburn occupy the same interval.

Bellevue.—The Monticulipora molesta beds of Nickles (1902) and the Rafinesquina alternata var. ponderosa zone of Cumings and Galloway (1913). This highly fossiliferous zone of thin and often cross-bedded and rubbly limestone extends south into Montgomery County on the east and Shelby County on the west. Thickness, 15 to 40 feet.

Corryville.—The Chiloporella flabellata zone of Nickles (1902). Other more or less characteristic fossils are Bythopora gracilis and Rafinesquina alternata var. fracta in abundance, together with Amplexopora filiasa, Hallopora andrewsi, Dekayia appressa, and Heterotrypa paupera.

The formation consists of thin-bedded fossiliferous limestone and shale. It has been regarded as missing in the section in Jefferson, Henry, and Shelby counties (p. 27) and may be traced south of the Ohio River for only a few miles. Whether the horizon is represented in the Tate or is unconformably out is not known. Thickness, 35 to 60 feet.

Mt. Auburn.5—The Platystrophia lynx beds of Nickles (1902). Platystrophia ponderosa var. auburnensis is characteristic around Cincinnati. Associated forms are Coeloclema oweni and Homotrypa pulchra in a limestone rubble. In the northern area of exposure along the eastern side of the Arch in Fleming and Mason counties the Mt. Auburn is most readily recognized by the presence of Monticulipora cf. mammulata which occurs in large numbers. Platystrophia ponderosa var. auburnensis is present but not as abundant as the species itself.

In the southern Blue Grass it is a similarly highly fossiliferous rubbly limestone with Platystrophia ponderosa, Heterospongia subramosa, and Amplexopora robusta common. Lithologically it is well marked, resting on the dense limestone of the Gilbert, and beneath the nonfossiliferous Sunset member of the Arnheim. It is position rather than anything in the fauna that seems to indicate its Mt. Auburn affiliation. Thickness, 10 to 35 feet.

Tate (Foerste, 1912).—Comparatively nonfossiliferous grey shale and fine-grained argillaceous limestone of the southern Blue Grass occupying the interval between the Fairmount and Gilbert. Northward on the eastern flank of the Arch normal Bellevue with Monticulipora molesta wedges in at the base in Montgomery County. Here and as far south as northern Clark County the formation has become abundantly fossiliferous with Platystrophia ponderosa, Amplexopora robusta, and Cyphotrypa clarksvillensis common. In Fleming County Monticulipora molesta is present as well as in the underlying Bellevue. Thickness, 60 to 80 feet.

Gilbert (Foerste, 1912).—This is a zone of dove to grey fine-grained to dense hard limestone restricted to the southern Blue Grass. It grades into the Mt. Auburn. Platystrophia ponderosa and Lophospira bowdeni are common. The Tate and Gilbert of Lincoln, Garrard, etc., counties together fill the interval occupied by the Bellevue and Corryville to the north. Ostracods are abundant in some layers and are similar to those found in the Sunset member of the Arnheim. Thickness, 0 to 20 feet.

In the western area of outcrop further work is also needed. According to Butts (1915) the Arnehim rests disconformably on the Bellevue at Sulphur in Henry County and at Madison, Indiana. McEwan (1920), however, has since shown the presence of both Corryville and Mt. Auburn in the latter section and the whole of the McMillan may well be present throughout this western area but with faunal expression and divisions unlike those of the Cincinnati area. In Shelby County there is a considerable section of McMillan overlying the normal Bellevue.

RICHMOND

The Richmond has customarily been recognized as beginning with the Arnheim, though the latter was originally classified with the Maysville and was again referred to it in 1913 by Cumings and Galloway. Although the Richmond has also been customarily regarded as latest Cincinnatian, it has been referred to the Silurian by Ulrich, Bassler, and others.

Arnheim (Foerste, 1905—the Warren beds of Nickles 1902).—At the type locality in Brown County, Ohio, Foerste placed the top at the lumpy limestone containing Strophomena concordensis. In Ohio the Arnheim succeeds the uppermost Mt. Auburn; in Tennessee it rests by overlap on rocks of various ages, usually the Leipers in the Central Basin and the Hermitage in western Tennessee along the Tennessee River. In the eastern and southern area of outcrop in Kentucky two divisions are recognized:

Sunset (Foerste, 1910).—A relatively nonfossiliferous shale and fine-grained argillaceous limestone series comparable to the Tate and Waynesville in character, sometimes dolomitic and frequently wave marked and sun cracked. Throughout the region of Garrard, Lincoln, Clark, and Montgomery counties it is capped by 2 to 4 feet of fine-grained hard limestone of the Gilbert type, in some layers of which ostracods are exceedingly abundant. This ostracod fauna is quite similar (Shideler, personal communication) to that of the Gilbert. Northward toward the Ohio River in the eastern area of outcrop the Sunset becomes fossiliferous and has Amplexopora robusta, which is so characteristic of the fossiliferous Tate and the "Mt. Auburn" of the southern Blue Grass. Thickness, 10 to 25 feet.

Oregonia (Foerste, 1910).—A highly fossiliferous, often rubbly limestone in which the characteristic Richmond brachiopods, Rhynchotrema dentatum var. arnheimensis, Leptaena richmondensis var. precursor, and Dinorthis carleyi (rare in Kentucky) are introduced. The association of any one of these species with Platystrophia ponderosa (upper limit of range) is regarded as diagnostic. Heterospongia knotti is rather characteristic in the area between Lincoln and Marion counties, but it has been found in the Mt. Auburn. Over much of this area the top is marked by about 2 feet of light-colored shale full of slender bryozoa, including a form resembling Hallopora dalei and a species of Homotrypa related to H. cylindrica. The contact with the Sunset is sharp. The Oregonia is in some places dolomitic, as occasionally in eastern Clark County and western Lincoln County. Thickness, 10 to 25 feet.

In Jefferson County, which may be regarded as typical of the western area, Butts (1915) recognized three divisions with a total thickness of 80 to, 100 feet:

(a) Platystrophia ponderosa zone (lowermost). Bluish lumpy clay rock and shale with much interbedded irregular knotty limestones. The zone is capped with a coarse-grained, locally cross-bedded limestone. Butts correlated this zone with the Sunset division.

(b) Rhynchotrema dentatum zone (associated with Leptaena richmondensis). Shale and interbedded thin limestones.

(c) Constellaria polystomella zone. Fossiliferous limestone and shale weathering into a more or less rubbly mass. Other common fossils are Anomalodonta gigantea, Homotrypa bassleri, Hallopora subnodosa, and Platystrophia cypha. Platystrophia ponderosa ranges through all these zones, Dinorthis carleyi is rare in both (a) and (c), and Cyclonema bilix var. fluctuatum occurs in all three. The rock is a limestone rubble.

In Shelby County and vicinity the interval between the typical Bellevue and the first occurrence of Leptaena richmondensis and Rhynchotrema dentatum is a zone of fossiliferous limestone carrying an abundance of Platystrophia ponderosa. How much of this zone belongs in Butts' zone (a) of the Arnheim and how much may be McMillan has not been determined.

In central Tennessee the Arnheim is restricted to the northern and western sides of the Nashville dome. It is a fossiliferous blue nodular limestone and shale characterized by an abundance of Rhynchotrema dentatum, Leptaena richmondensis, and Dinorthis carleyi. In addition to these characteristic forms Streptelasma rusticum, Rhynchotrema capax, Sowerbyella rugosus var. clarksvillensis, Protaraea richmondensis, Columnaria alveolata, Rhombotrypa quadrata, Strophomena planumbona, Hebertella insculpta, and Dinorthis subquadrata are found. These forms do not occur at this level in the Kentucky Richmond and are, all of them, rather characteristic of the Liberty.

Accurate measurements of the thickness of the Arnheim in the western area in Kentucky are not available. The Constellaria zone ranges from 18 to 27 feet, the R. dentatum zone, 8 to 40 feet, and the P. ponderosa zone, 32 feet with the base unexposed (Butts, 1915, pl. 5). The discrimination of this last-named zone is a part of the general McMillan problem mentioned above.

| PLATE IV | |

|

|

| FIG. 1. Camp Nelson limestone

showing the characteristic honeycombed weathered surface, near Boonesboro. |

FIG. 2. Jessamine limestone,

Marble Creek, southeastern Jessamine County. |

|

|

| FIG. 3). Undifferentiated

Tate-Mt. Auburn, and Arnheim section in quarry on the Clay City road just west of Howards Creek, 9 miles southeast of Winchester. The Sunset member of the Arnheim is composed of 14 feet of more or less barren shale and clay rock capped by a 3½-foot zone of hard, fine-grained limestone, (man with hammer). Near the top of this is a layer bearing a profusion of ostracods. This ostracod, hard limestone zone is rather characteristic of the lower Arnheim from Clark County to Boyle County. |

FIG. 4). Nicholas limestone,

the quarry rock member of the upper Cynthiana. Quarry at North Middleton, southeastern Bourbon County. Its upper limit is rather consistently marked by the Rogers Gap beds, but the horizon of the base varies. |

Waynesville (Nickles, 1903).—Cumings (1901) used the term Dalmanella meeki zone. Three members are recognized (Foerste, 1909) in Ohio:

Fort Ancient.—Characterized by the abundance of Dalmanella meeki and absence of other characteristic Richmond brachiopods and corals. Anomalodonta gigantea, Modiolopsis concentrica, Whiteavesia pholadiformis, Opisthoptera fissicosta, and Pterinea demissa are common. The top is marked by the Orthoceras duseri bed.

Clarksville.—This member includes all strata on up to the lower Hebertella insculpta zone (Austin, 1927, included the Hebertella insculpta zone in the Clarksville). Streptelasma rusticum, Sowerbyella rugosus, Strophomena planumbona, S. sulcata, Rhynchotrema capax, and Leptaena richmondensis are common. It may be traced southward into Fleming County, Kentucky (Foerste, 1935) but is not recognized in the western area of outcrop.

Blanchester.—Terminated by the upper Hebertella insculpta zone, which has commonly been recognized as marking the base of the Liberty but has more recently been included in the Waynesville (Foerste, 1909f). It has the richest fauna of the Waynesville and may be traced south into Bath County, Kentucky. Strophomena nutans, S. neglecta, and S. vetusta form a well-marked zone in the middle. Leptaena richmondensis, Rhynchotrema capax, Platystrophia clarksvillensis, and P. cumingsi are common.

In Jefferson and adjoining counties the Waynesville is a succession of shales and fine-grained earthy limestones, the base marked by the occurrence of Columndria alveolata and Tetradium minus (Fisherville coral reef of Foerste, 1909f). Above is a zone of shale with Cyphotrypa clarksvillensis common. The rest of the formation is sparingly fossiliferous with C. clarksvillensis (also in Arnheim) and Zygospira kentuckiensis characteristic. The thickness here is about 40 feet.

Across the southern Blue Grass the Waynesville is almost devoid of fossils but becomes again fossiliferous with Cyphotrypa at the base to the north in Montgomery County. The thickness throughout this region ranges from about 40 to 60 feet.

Liberty7 (Nickles, 1903).—The Strophomena-Rhynchotrema bed of Cumings (1901) and Strophomena planumbona zone of Cumings and Galloway (1913). Over most of its area of outcrop in Kentucky the base is marked by a coral reef, the Bardstown reef of Foerste (1909f) composed of Columnaria alveolata, C. vacua, Tetradium minus, Calapoecia cribriformis, and the associated Beatricia undulata, and B. nodulifera. It may be traced southward into Lincoln County on the one side and Marion County on the other. The Liberty is frequently missing along the axis of the Arch. The more characteristic species include Dinorthis subquadrata, Sowerbyella rugosus, Rhynchotrema capax, Strophomena planumbona, Streptelasma rusticum, Rhombotrypa quadrata, R. subquadrata, Protaraea, richmondensis, and Homotrypa austini. In the region between Lincoln and Montgomery counties, at least, the basal reef is often not developed and the bottom of the formation is marked by a massive dolomitic limestone. Hebertella insculpta, however, is present, associated in place with an occasional Columnaria. The rest of the limestone over this same region is more or less dolomitic, associated with much shale, and fossils are few and not well preserved. Strophomena sulcata, Bythopora meeki, B. delicatula, and occasionally Rhynchotrema capax are present. The upper part of these beds referred to as Liberty may include the Whitewater.

At Louisville the thickness is 35 to 50 feet; across the southern Blue Grass, up to 65 or 70 feet. At Agawam Station in Clark County 90 feet of beds intervene between the Waynesville and Brassfield. The Whitewater is probably represented in the upper part.

|

PLATE V |

|

|

|

| FIG. 1. Upper Waynesville and lower Liberty formations. Columnaria-Tetradium reef (hammer) marking the base of the Liberty, U. S. Highway 60 between Shelbyville and Louisville, 1 mile east of the Shelby-Jefferson county line. | FIG. 2. Cynthiana section at Renick Station, 6 miles northwest of Winchester, Clark County. The persistent Stromatocerium zone is shown a few feet above track level and the Nicholas limestone at the top of the cut. At the Stones Road cut on the Southern Railroad a few miles south of Lexington where the lower Cynthiana is missing, the Stromatocerium forms the base of the formation. |

|

|

| FIG. 3. Garrard sandstone, Agawam Station section, Clark County, just south of the tunnel. | FIG. 4. Rubbly Millersburg phase of the Cynthiana a few feet above the zone of Allonychia flanaganensis, 6 miles west of Winchester on U. S. Highway 60. |

Saluda (Foerste, 1902).—A heavy dolomitic limestone, scantily fossiliferous in Kentucky except for an upper member, the Hitz limestone (Foerste, 1903). The latter was earlier designated as the Lophospira hammelli bed (Foerste, 1897) and contains a Whitewater fauna. In the lower part of the formation a few feet above the base, a reef of Columnaria and Tetradium, similar to the lower reefs, is a characteristic horizon marker. This is the Madison coral reef of Foerste (1909f). Some layers of the Hitz limestone member are full of ostracods, including Eurychilina striatomarginata, Leperditella ? glabra, and Leperditia caecigena.

In Jefferson County the Saluda is 40 feet thick, of which up to 6 feet is the Hitz member.

The Whitewater (Nickles, 1903) of Ohio and Indiana and the Saluda of Kentucky and southern Indiana are contemporaneous phases of sedimentation, the former wedging out and overlapping the Saluda to the south where it is represented by the Hitz member. The Saluda correspondingly thins northward. The Whitewater may be represented in the upper part of the "Liberty" on the eastern flank. The beds here, though, are without fossils.

The fauna is much like that of the Liberty, the bryozoa Batostoma variable and Homotrypa nicklesi being restricted to it. Other common forms include Bythopora delicatula, Homotrypa cylindrica, H. ramulosa, H. wortheni, Homotrypella rustica, Monticulipora epidermata, Rhynchotrema dentatum, R. capax, Strophomena sulcata and Platystrophia acutilirata and varieties.

Elkhorn. Unknown in Kentucky.

Footnotes

1

In the 1941 edition of Schuchert and Dunbar's Historical Geology (John

Wiley and Sons) the correlations of the several formations of the High Bridge

have been materially changed. The Tyrone was removed from the Lowville and

placed at the base of the Trenton. The Camp Nelson was removed from the Stones

River and along with the Oregon placed in the upper Black River and correlated

with the Lowville and Chaumont of the New York section. This changes the

subsurface picture somewhat.

2 A fourth has been observed (Young, 1940) about 25 feet above the top of the

Tyrone in the upper Curdsville or lower Hermitage. There are others.

3 Occurs also in the Tyrone.

4 This species has been commonly identified and listed as Heterotrypa

parvulipora.

5 Harmon (Cumings and Galloway, 1913).—Referred to as the Rafinesquina

alternata var. fracta zone. It included the Corryville, Mt. Auburn, and Arnheim

formations of Indiana. The most common fossils are R. alternata var. fracta and

Hallopora ramosa. Characteristic forms, according to Cumings and Galloway, are

Atactoporella ortoni, Coeloclema oweni, Homotrypa pulchra, and Dinorthis

retrorsa (carleyi.) The name was introduced due to difficulty in differentiating

the three.

6 Orton, 1873.

7 Because of close faunal relationship between the Waynesville and Liberty, Foerste (1912) used the name Laughery formation for the whole succession.