Clays are rather widely distributed in the state. Most common are the residual clays from the weathering of limestone and shale, and they are suitable for the manufacture of common brick and cheap tile. Alluvial clays of flood plains and terraces are available along the larger streams. A large fire clay industry centers around the Pottsville clays of Olive Hill, Carter County, and vicinity. In Madison County the Irvine (Tertiary) clays are the basis for a brick, tile, and pottery industry. The ball clays, and associated sagger and wad clays of the Holly Springs (lower Eocene) formation of Graves and Ballard County in the Purchase are outstanding.

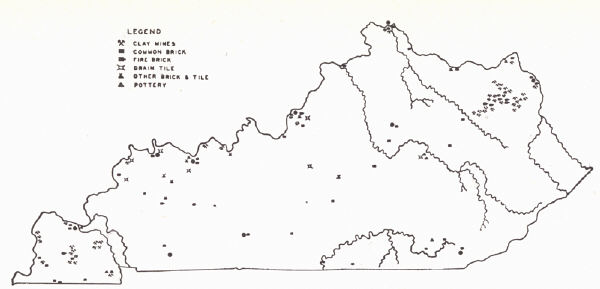

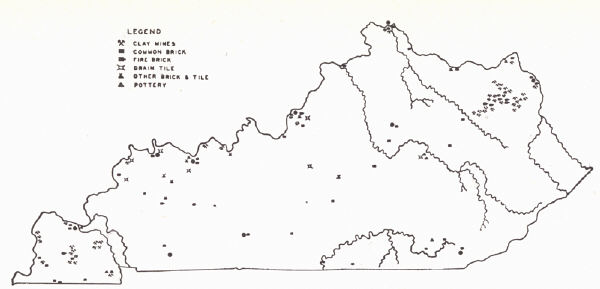

| PLATE CXVI | |

|

|

| FIG. 1. Clay mines and clay products plants in Kentucky. | |

|

|

| FIG. 2. Ball clay production in Kentucky,1921-1938. | FIG. 3. Fire clay production in Kentucky, 1921-1938. |

BLUE GRASS

Available clays include: (a) the Eden shale of northern Kentucky, either fresh or weathered, (b) the widespread residual clay from :many Ordovician limestones and shales and from the Silurian and Devonian limestones and shales around Louisville and vicinity and the eastern Blue Grass, and (c) the alluvial floodplain and Pleistocene terrace clays. The Eden has not been used in Kentucky but has been used in both the fresh and weathered condition at Cincinnati and vicinity. Southward, though, the proportion of limestone in this formation increases. Residual clays from Ordovician limestones are used in Marion, Jessamine, and Fayette counties for common brick. In Jefferson County such clays from the Jeffersonville limestone are used for the manufacture of common brick and drain tile. At Maysville common, pressed, and rough-textured brick is made from Pleistocene terrace clays in the Ohio River valley. Common brick is made from floodplain clays at Covington, and formerly also in Carrol County. Companies manufacturing hollow block, fire brick, and stoneware at Louisville, and floor and wall tile at Covington import their clays from elsewhere.

Clays of the Irvine formation are referred to under the Knobs.

KNOBS

Available and commercialized clays include:

(a) Floodplain and terrace (Pleistocene) clays along the Ohio and other larger rivers. These are used for common brick and drain tile at Salt Lick (Licking River), and similarly Red River clays in Powell County.

(b) Waverly (east side of Arch), New Providence (south and west side of Arch), and Rosewood (Louisville vicinity) shales. These formations out¬crop extensively in the Knobs, are used in places, and constitute a large available supply. The New Providence shale is used in a number of plants near Louisville for common, face, and paving brick, hollow block, drain tile, and red earthenware. (See also under Eastern Coal Field.)

(c) The clay from the weathered Ohio (New Albany-Chattanooga) black shale is used in Nelson County for common brick and drain tile. These shales are not of value when fresh, and when weathered are regarded as less desirable than the associated New Providence shale.

(d) In Madison County high terrace clays of the Irvine formation along the Kentucky River are used at Waco and Bybee for the manufacture of stoneware, blue art pottery, brick, and tile. The deposits (earlier alluvium) are never deep nor of great extent.

(e) The Estill and Lulbegrud shales of the Silurian east of the Arch are smooth, plastic, red-burning shales which can be (but at present are not) used for brick, hollow block, drain tile, and earthenware.

EASTERN COAL FIELD

The Eastern Coal Field is the region east of the bordering Pottsville-Waverly Escarpment and includes thus a limited area in Lewis and Rowan counties involving older rocks more characteristic of the Knobs. These include Silurian shales, the Ohio shale, and the Waverly. The latter is mined and used at Firebrick in Lewis County for paving block. Considerable thicknesses of shale are available in the Pennington formation in the southern part of the western margin and again along Pine Mountain. Shales are also available in the Pottsville, Allegheny, and Conemaugh series as well as some underclays. Little has been done with them. A brick plant at Woodbine in Whitley County uses a residual clay derived from such shales.

As in other parts of the state floodplain and terrace clays of the Pleistocene are available along the rivers. These are used for the manufacture of brick in Boyd County and near Barbourville.

The Olive Hill fire clay is an outstanding material. This clay region centers in Carter County and extends north into Ohio and occupies an area of about 660 square miles. The clay is lenticular and is thus not consistently present throughout. Development has been in the zone bordering the Chesapeake & Ohio Railroad. The whole area, though, has been pretty thoroughly drilled, and extensive undeveloped areas are held by operating companies either in fee simple or by mineral rights. The clay occurs at the contact between the Pottsville and underlying rocks, so that clay operations are restricted to the area of outcrop of this contact. There are three grades: (a) flint, (b) semi-hard (semi-flint or soft hard), and (c) No. 2 plastic.

The flint clay is very fine grained, usually buff or grey but occasionally black or even red, and has conchoidal fracture. An oolitic variety is locally developed, the oolites consisting of gibbsite or hydrargyllite (Greaves-Walker, 1907 and Galpin, 1912) embedded in a matrix of normal flint clay. Impurities consist of pyrite concretions, veinlets of gypsum and rarely galena. Principal mineral constituents are kaolinite and hydromica. Quartz is present where the clay grades laterally into sandstone.

The semihard clay differs in being slightly softer, in having noticeable plasticity, and in the presence of numerous slickensided surfaces traversing it in all directions. It is usually sharply separated from the flint variety.

The No. 2 plastic clay is softer and has decided plasticity. Slickensides are abundant. It is the least refractory of the three.

The clay rests normally on the Mississippian limestone (St. Louis-Chester), sometimes on the Waverly formation where the former is missing. It is commonly separated from the limestone by a red mottled plastic clay of low refractoriness ("pinkeye"), sometimes sandstone (up to 25 feet) or shale (up to 22 feet). The nature of the floor may vary within the same mine. The clay is overlain by various sediments, coal, shale, sandstone, or conglomerate.

The clays are regarded as Pottsville though Miller (1919) called attention to an occurrence near Blaire Mill, Rowan County, where the clay is overlain by Mississippian limestone. Ries (1922) pointed out that this deposit is not fire clay, nor has limestone been found above fire clay in the hundreds of test holes drilled in the region.

In regard to origin, the clay has commonly been believed to be residual from the Mississippian limestones and formed during the Mississippian-Pennsylvanian interval. The locally intervening sandstone, though, renders this explanation untenable for at least these places, and they are presumably lacustrine and alluvial. Six feet is regarded as a workable thickness, and a thickness of 27 feet is attained at Olive Hill. Occasional pockets occur in the conglomerate (transported).

Mining operations are mainly in Carter County and center around Olive Hill, Aden, Grahn, Enterprise, Hayward, and Soldier. A large part of the clay is burned in the same vicinity, but some is shipped out to Ashland, Louisville, etc.

The Allegheny series has a plastic fire clay associated with the Van Port (ferriferous) limestone 10 to 40 feet above the Homewood sandstone. The clay was formerly mined in the vicinity of Ashland and Catlettsburg and also in Carter County. It is not so refractory as the flint and semi-hard clays of the Olive Hill district, though some is mixed with these clays. There was only one mine in operation at the time of Ries' report (1922) a mile northwest of Ashland where it was used for fire brick. Crider (1913) stated that it has been used for pottery. Apparently there is a general zone of clay at this horizon within which the fire clay occurs, here at one level, elsewhere at another, since it occurs in some places above and in others below the limestone, which itself is not consistently present. Local pockets of flint fire clay occur within it.

MISSISSIPPIAN PLATEAUS

Clays and loams of floodplain and terrace deposits are used. At West Point common and rough-textured brick are manufactured from this material. Available Mississippian rocks of this area include the extensive Buffalo Wallow = Leitchfield shales in the region between Warren and Meade counties. They are used for roofing and floor tile at Cloverport. Other shale zones occur within the Chester. The Meramec and Chester limestones yield residual clays which are widespread and suitable for the manufacture of common brick.

Deposits of fire clay, regarded as Lafayette were at one time (1899-1902) worked near Smithland for fire brick. The clay is overlain by the Lafayette sands or gravels and is either a Mississippian limestone residuum or Tertiary transported clay. Another former operation of interest was the Stephens fire clay mine southeast of Salem on the Livingston-Crittenden county line. It is said to have been a residual (?) clay occupying a fault fissure between limestone and quartzite (Ries and Leighton, 1909).

WESTERN COAL FIELD

Available commercial clays include:

(a) Surface clays and loams of floodplain and terrace deposits found bordering streams. These are suitable for the manufacture of common brick, less often face brick, and sometimes drain tile, and are used at Henderson, Sturgis, Uniontown, and Sebree for the manufacture of these products.

(b) Pottsville and Allegheny shales, either fresh or weathered. Many are underclays, but none so far as known are fire clay. An Allegheny underclay from Lamkin, Hancock County, is used for flue linings. A similar clay (Pottsville) found in Hawesville is used for small size sewer pipe. At Madisonville weathered shale is used for the manufacture of common, face, and low grade fire brick, hollow block, and drain tile.

(c) Pockets of white clay occur immediately beneath the Caseyville conglomerate in Hart, Edmonson, and Taylor counties. Some pockets contain partially disintegrated pebbles from the conglomerate.

PURCHASE REGION

Commercial clays of the region include ball, sagger, wad, and brick clays of which the common brick variety is widespread and the ball, sagger, and wad clays more restricted. The latter are mined only in Graves and Ballard counties from the Holly Springs formation and on a small scale from the Ripley in Marshall County. Clay producing formations include:

Quaternary.—Recent and Pleistocene surficial and alluvial clays are widespread in the Purchase and have been used for brick in a number of places. A large plant using these materials is located at Mayfield. Pleistocene loess is not used in Kentucky, though large deposits occur along the Mississippi River bluffs in the western counties. A large brick plant at Memphis, Tennessee, uses it.

Tertiary:

(d) Jackson formation—not used.

(c) Grenada (gypsiferous)—not used.

(b) Holly Springs.—This is the all-important zone of ball, sagger, and wad clays both in Kentucky and Tennessee. The No. 4 pit near Pryor was the first operation and is the largest of the region including Tennessee. Operations are mainly in Graves County in the vicinity of Mayfield and in Ballard County near Wickliffe. Manufactured articles include sanitary wares, floor and wall tile, potters supplies, table ware, terra cotta, porcelain, abrasives, etc.

The clay occurs as lenses in the sand and is in places too sandy for use. It varies from light grey to buff to lignitic, depending on the quantity of organic matter present. Color has little to do with the value and some of the very dark clays are high grade. The section at the old No. 4 pit northeast of Pryor is given below (Roberts and Meacham, Kentucky Geol. Survey, unpublished manuscript):

Section in Clay Pit

(Old Number 4)

Northeast of Pryor, Graves County

(largest clay pit in Kentucky)

Soil from reworked loam with some sand and gravel............. 1-2 ft.

Loam, and probably some loess, light yellowish brown when

dry, porous, few

gravels, uniform texture, grades downward

into

gravels.......................................................................... 3-8 ft.

Plio-Pleistocene deposits: gravels bedded, and some

oriented, all are rounded or

flattened, composed of chert,

quartz, and a few of quartzite and jasper, average

from ¼

to ½ inch major diameter, and some attain as much as 5

inches diameter.

Sand is orange colored, cross bedded, coarse to medium

texture, not highly

consolidated except for a few thin

layers near the base. About the same

composition as the

gravels. Some of the sand is more highly iron stained than

other, and some grains coated with a film of iron oxides.

The gravels contain fragments of Lithostrotion corals,

bryozoa, brachiopods,

gastropods, and pelecypods.

Gravel and sand

exposed..................................................... 20-32 ft.

————Unconformity————

Holly Springs formation:

12.—Lignitic clay, dark brown to black, fragments of

stumps and limbs all turned

into lignite; well laminated,

little plasticity, few sand layers, numerous plant

stems but

not identifiable; this is left on the clay by the steam shovel

to

protect it, and removed to the dumps as clay is

mined................................................................................ 10-14 in.

11.—Sagger clay, light gray color, frequent stems

lignitized, carbonized leaves,

carries small amount

of silica................................................................................ 3½-4 ft.

10.—Lignitic clay, very dark to black, high in

organic matter.................................................................... . 1-1 ¼ ft.

9.—Ball clay, light to medium gray, rather streaked,

frequent

plant stems badly preserved; this was known as

Old Mine No.

2 clay. ............................................................ 3 ft:

8.—Ball clay, dark to black...................................................... 1½ ft.

7.—Ball clay, light gray, rather massive and no trace

of plants,

no lamination, highest grade of ball clay, and

Old Mine No. 3..................................................................... 3½-4 ft.

6.—Clay, lignitic, dark to black, ball variety of fairly

high grade.

..............................................................................l¼ ft.

5.—Lignitic clay, dark to black, not used due to too

high content

of lignite............................................................... l¼ ft.

4.—Clay, yellowish gray in places, very massive, and

shows little

tendency towards lamination, rather uniform;

known as Oliver

No. 4..... ............... ....... .............................. 4 ft.

3.—Clay, dark gray, massive, and shows no trace of plants;

known as Oliver No. 5......................................................... 4½-5 ft.

2.—Clay, dark gray, massive, uniform, known as

Old No. 6.......................................................................... 5½-6½ ft.

1.—Sand, reported from many test holes.

Local potteries have been operated in the past at Lynnville, Hickman, and Paducah. Roberts and Meacham2 listed only one active in 1929 in southeastern Graves County. It was not in operation the year round.

(a) Porters Creek.—The Porters Creek formation is not a source of ceramic clays but is mentioned by Whitlatch (1940) as the most promising undeveloped ceramic material in Tennessee. Tests made on it a decade ago indicate its possible use as a substitute for Fullers earth. Although apparently effective in removing much of the color from oils, it is not a true Fullers earth. It is the only clay of marine origin in the Tertiary of western Kentucky.

Cretaceous.—The Ripley formation carries a white-burning laminated clay, varying from light colored to drab to dark grey (organic matter) in its original color. It has been extensively used for brick and pottery and 40 years ago was used at Pottertown, Galloway County, for the manufacture of crocks, churns, jugs, and sanitary wares.

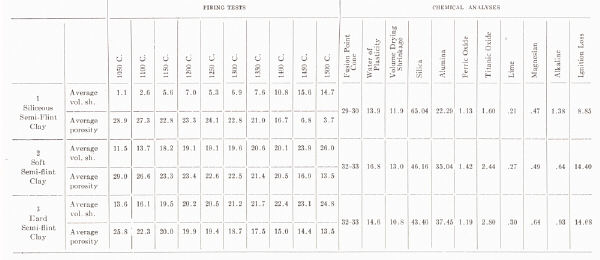

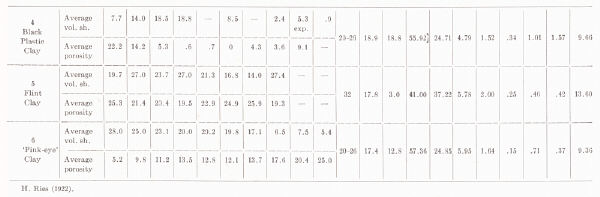

| REPRESENTATIVE TESTS AND ANALYSES OF OLIVE HILL FIRE CLAY |

|

|

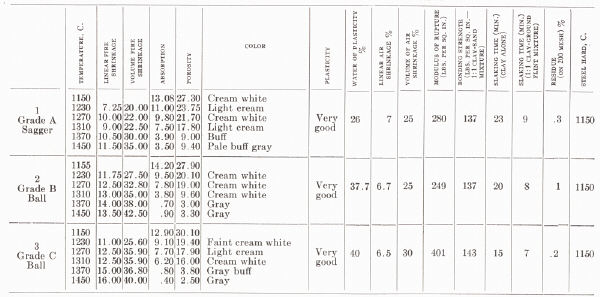

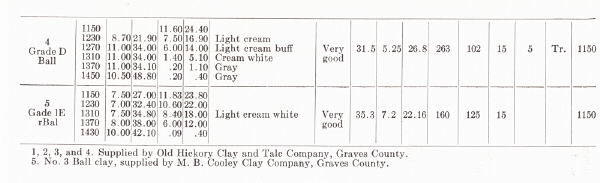

| REPRESENTATIVE TESTS OF HOLLY SPRINGS CLAY |

|

|

Footnotes

1 These notes are taken mainly from: (a) Ries (1922), (b) Crider (1913), (c) a

short unpublished manuscript dealing with Kentucky clays by the late R. P.

Meacham, and (d) an unpublished manuscript on the geology of the Jackson

Purchase by Roberts and Meacham, Kentucky Geology Survey.

2 Geology of the Jackson Purchase Region, Kentucky, unpublished manuscript,

Kentucky Geol. Survey.