Chapter 27

Approach to the Patient with Hypercholesterolemia

Mason W. Freeman

Over the last several years, evidence has accumulated

demonstrating that treatment of hypercholesterolemia can reduce

atherosclerosis and its attendant cardiovascular complications (see Chapter 15).

These findings have heightened physician and patient awareness of the

importance of hypercholesterolemia. The primary care physician needs to

be capable of evaluating hypercholesterolemia and of designing and

implementing a treatment program that effectively uses dietary

treatment, exercise, weight loss, and, when necessary,

cholesterol-lowering drugs.

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY (1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8)

The production of atherogenic lipoproteins and the

induction of atheromatous plaques by those lipoproteins involve

distinct pathways. The presence of an elevated serum cholesterol level

does not, by itself, guarantee the development of atherosclerotic

lesions that will become clinically important any more than a normal

cholesterol concentration ensures plaque-free coronary arteries. The

formation and subsequent rupture of atherosclerotic lesions, leading to

the acute coronary syndromes of

unstable angina and myocardial infarction, depend on complex cellular and metabolic interactions. Serum lipids, inflammatory cells recruited to the sites of lipid deposition, the normal cellular constituents of the artery wall, and components of the blood coagulation system all contribute to the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis and its clinical consequences.

P.191

unstable angina and myocardial infarction, depend on complex cellular and metabolic interactions. Serum lipids, inflammatory cells recruited to the sites of lipid deposition, the normal cellular constituents of the artery wall, and components of the blood coagulation system all contribute to the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis and its clinical consequences.

Lipoproteins

An understanding of lipoproteins and their metabolism

helps to guide physicians in evaluating and treating lipid disorders.

To circulate in the aqueous environment of the blood, nonpolar lipids

such as cholesterol and triglyceride are complexed with proteins and

the more polar phospholipids into spheres called lipoproteins. The protein components of the lipoproteins are known as apoproteins,

which play both structural and functional roles in the metabolism of

lipid particles. Genetically inherited mutations in either the

structure of apoproteins or the receptors that bind them account for

many of the most severe forms of hyperlipidemia. The lipoproteins are

usually divided into four major classes based on particle density,

which is a reflection of their relative protein and lipid content: chylomicrons, very low density lipoproteins (VLDLs), low-density lipoproteins (LDLs), and high-density lipoproteins (HDLs). There are also subdivisions and minor classes of lipoproteins (Table 27.1).

Table 27.1. Lipoprotein Composition | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Chylomicrons

Chylomicrons derive from dietary fat and carry

triglycerides throughout the body. They have the lowest density of all

lipoproteins and will float to the top of a plasma specimen left in the

refrigerator overnight. The chylomicron itself is probably not

atherogenic, but the role of the triglyceride-depleted chylomicron

remnant is uncertain. Triglyceride makes up most of the chylomicron and

is removed by the action of lipoprotein lipase. Patients deficient in

this enzyme or its cofactors (insulin and apolipoprotein CII) have very

high serum triglyceride levels and increased risk of acute pancreatitis.

Very-Low-Density Liproproteins

VLDLs are also triglyceride rich and are acted on by

lipoprotein lipase. Their function is to carry triglycerides

synthesized in the liver and intestines to capillary beds in adipose

tissue and muscle, where they are hydrolyzed. After removal of their

triglyceride, VLDL remnants can be further metabolized to LDL. The

atherogenicity of native VLDL is controversial, but the metabolism of

VLDL to atherogenic lipoproteins is not in doubt. VLDLs serve as

acceptors of cholesterol transferred from HDL, possibly accounting in

part for the inverse relation between HDL cholesterol and VLDL

triglyceride. The serum enzyme cholesterol ester transfer protein

mediates the process.

Low-Density Lipoproteins

LDLs are the major carriers of cholesterol in humans.

They carry cholesterol to tissues and deliver it via receptors on the

cell surface that bind and internalize the LDL particle. LDLs are the

lipoproteins most clearly implicated in atherogenesis. LDL levels are

increased in individuals who consume large amounts of saturated fat

and/or cholesterol. There are also several Mendelian genetic disorders

that result in increased LDL levels. These disorders include mutations

that produce defective LDL receptors (familial hypercholesterolemia) or

mutant proteins that interact with the LDL receptor (autosomomal

recessive hypercholesterolemia). LDL levels can also result from

genetically encoded abnormalities in the structure of LDL apoprotein B.

Finally, there are non-Mendelian, polygenic disorders that cause

increases in LDL.

When serum LDLs exceed a threshold concentration, they

traverse the endothelial wall and can become trapped in the arterial

intima. There, they may undergo oxidation, aggregation, or other

modifications that cause their uptake by macrophages. This process

appears to be an important initiating step in atherogenesis. The

association of serum total cholesterol with coronary heart disease

(CHD) is predominantly a reflection of the role of LDL because LDL

cholesterol constitutes the bulk of serum cholesterol in most humans.

Many well-designed studies demonstrate that lowering the LDL

cholesterol can dramatically reduce subsequent coronary events and

all-cause mortality in hypercholesterolemic patients.

High-Density Lipoproteins

HDLs appear to function in peripheral tissues as an

acceptor of free cholesterol that has been transported out of the

cellular membrane. The cholesterol is esterified and stored in the

central core of the HDL and may be further metabolized. This reverse

transport system may explain why patients with very high HDL levels

have a reduced risk of developing CHD, even if their LDL levels are

elevated.Apolipoprotein AI is the major

apoprotein of HDL, and its level also inversely correlates with the

risk of CHD. Women have higher levels of HDL cholesterol than men, in

part because of their higher estrogen levels. Exercise increases HDL,

whereas obesity, hypertriglyceridemia, and smoking lower HDL. The

HDL-cholesterol concentration is the single most powerful lipid

predictor of CHD risk, but therapies that raise HDL-cholesterol levels

have proven difficult to develop, and the significance of such an

intervention on coronary disease outcomes is uncertain.

P.192

Dietary Influences

Dietary fat and cholesterol have a substantial influence

on serum- and LDL-cholesterol levels. Saturated fat intake has a

greater effect on serum cholesterol than does dietary cholesterol

intake. For each increase in percentage of total calories contributed

by saturated fats, serum cholesterol increases by a factor of 2.16,

whereas the serum cholesterol increase is only 0.068 for each

percentage increase in dietary cholesterol. This relationship is

summarized in the equation of Hegsted:

Change in total cholesterol = 2.16 delta S – 1.65 delta P + 0.068 delta C

where delta S, delta P, and delta C are the changes in

the percentage of total calories contributed by saturated fats,

polyunsaturated fats, and cholesterol, respectively. Fats are

characterized by their constituent fatty acid composition. The fatty

acids are characterized as saturated, polyunsaturated, or

monounsaturated. The state of saturation refers to the number of

carbon–carbon double bonds contained in the fatty acid.

Saturated Fatty Acids

Saturated fatty acids can raise LDL cholesterol, in part

by altering the LDL receptor's catabolic activity. The long-chain

saturated fatty acids common to the American diet—lauric (12 carbons),

myristic (14 carbons), palmitic (16 carbons), and stearic (18

carbons)—have no double bonds and are not essential for human growth

and development. Not all saturated fatty acids trigger rises in LDL

cholesterol. For example, stearic acid and some shorter chain fatty

acids (caproic and caprylic) do not. In the typical American diet,

about one-third of the saturated fat content derives from meat and meat products, whereas another one-third comes from dairy products and eggs, and 10% from baked goods. Vegetable oils also may contain saturated fat (see Appendix I), especially the so-called “tropical oils”

(coconut and palm) and cocoa butter, which are commonly used in

commercial food preparation. Even when unsaturated oils (see later

discussion) are used in processed foods, they usually undergo partial hydrogenation,

which adds back hydrogens to the carbon–carbon double bonds,

eliminating some double bonds and making the fatty acids more

saturated. This saturation process is performed to make these oils more

solid at room temperature, but it also makes them more

hypercholesterolemic.

Monounsaturated Fatty Acids

Monounsaturated fatty acids are present in all animal and vegetable fats. The most common dietary form is oleic acid,

plentiful in peanuts, almonds, olives, and avocados. Oils derived from

these sources neither raise nor lower LDL cholesterol by themselves,

although cholesterol and CHD risk fall if they are used as substitutes

for saturated fat. Mediterranean diets rich in olive oil and other sources of monounsaturated fatty acids appear to be relatively nonatherogenic, even though they are not low in fat.

Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids

Unlike saturated and monounsaturated fatty acids,

polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) are not synthesized by the body.

They must be present in the diet and are referred to as essential fatty acids.

The location of the first double bond from the methyl end of the

molecule determines the nomenclature of the PUFAs. The major dietary

fatty acids contain either an n-6 or n-3 first double bond. Linoleic and arachidonic acids are the common Ω-6 PUFAs, found in considerable quantities in liquid vegetable oils

(sunflower, safflower, corn, and soybean). The Ω-3 fatty acids are

represented by linoleic acid (found in canola oil and leafy vegetables)

and the Ω-3 fish oils (eicosapentanoic and

docosahexanoic acids). The latter attracted considerable interest when

epidemiologic studies found a link between their consumption and

reduced rates of CHD mortality.

When vegetable oils rich in PUFAs are subjected to partial hydrogenation in commercial food processing, not only do some of their double bonds get converted to single bonds, but others shift from the cis configuration to the trans

configuration, which increases their atherogenicity and associated CHD

risk. Intake of such substances increases LDL cholesterol,

lipoprotein(a) (LPa), and triglycerides and reduces HDL cholesterol.

Data from the Nurses' Health Study suggest that replacing trans

unsaturated fats in the diet with polyunsaturated fats can reduce CHD

risk by nearly 60%, a much greater reduction than even that achieved by

reducing overall fat intake.

Cholesterol

As the Hegsted formula indicates, dietary cholesterol

has a much smaller effect than saturated fatty acids on raising total

cholesterol. For every additional 100 mg of dietary cholesterol

consumed per day, the serum cholesterol will rise by about 8 to 10

mg/dL. However, organ meats (e.g., brain, kidney, heart, sweetbreads) and egg yolks are concentrated sources of dietary cholesterol (see Appendix II) and can have a substantial effect on serum cholesterol levels. Although shellfish

contain moderate amounts of cholesterol, they have relatively small

amounts of saturated fat and are sources of Ω-3 PUFAs. Cholesterol is

absent from food derived from plants. Plant stanols and sterols can

actually block cholesterol absorption in the intestine, and a

commercially available margarine containing the plant stanol sitostanol

is available as a cholesterol-lowering agent. It reduces serum

cholesterol levels by 10% to 15%. Recently released National

Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) guidelines (Adult Treatment Panel

[ATP] III) encourage the use of these plant stanols in dietary programs

aimed at reducing blood cholesterol levels.

Other Dietary Factors

Low-fat, high-carbohydrate diets

can reduce HDL cholesterol and increase triglycerides. Especially in

obese persons, increased total caloric intake may induce overproduction

of VLDL triglycerides while reducing HDL cholesterol levels. Data from

the Nurses' Health Study suggest that substituting carbohydrate for saturated fat in the diet may reduce CHD risk by about 15%, but substituting carbohydrate for polyunsaturated fat

may increase CHD risk by greater than 50%. There is no evidence that

either dietary carbohydrate (whether simple sugars or complex ones) or

protein significantly affects LDL cholesterol.

The fiber content of food has generated much interest. Insoluble fiber

(typically cellulose found in wheat bran) has no cholesterol-lowering

effect, although it is beneficial for lowering the risk of diverticular

disease and colon cancer (see Chapter 65). Soluble fiber (pectins, certain gums, psyllium) has received much attention in the lay press stimulated by claims about oat bran,

which contains the gum beta-glycan. Initial studies were encouraging,

but subsequent data suggested the cholesterol decreases observed were

no greater than those found with use of insoluble fiber and probably

resulted from replacement of dietary fat in the diet rather than from a

direct effect on lipid metabolism. When studied in patients already

taking a low-fat

diet, high-soluble-fiber intake appeared to lower serum cholesterol by a modest amount (3% to 7%).

P.193

diet, high-soluble-fiber intake appeared to lower serum cholesterol by a modest amount (3% to 7%).

WORKUP (2,9,10,11,12,13,14)

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of hypercholesterolemia (see also Chapter 15) should always be based on repeat measurements

of serum lipids because combined analytic and biologic variations in

serum lipids range from 10% to 20%. A single measurement should never

be viewed as sufficient for a diagnosis of hypercholesterolemia. A venous sample processed in a laboratory meeting Centers for Disease Control and Prevention standards for cholesterol determination (see Chapter 15) is recommended.

Although earlier guidelines often recommended a stepped

approach to performing lipid analyses in patients, the ATP III

guidelines now suggest that a fasting lipid profile be done at the

initial assessment, whenever possible (Table 27.2). A fasting venous sample for determination of serum cholesterol, HDL cholesterol, and triglycerides

(with calculation of LDL cholesterol derived from these determinations;

see later discussion) constitutes the traditional lipid profile and the

basis for estimating VLDL cholesterol and calculation of LDL

cholesterol. The results characterize the lipid disorder and guide

treatment decisions. If a fasting lipid profile cannot be readily

arranged, then a practical alternative in persons at low CHD risk is to

obtain nonfasting determinations of total cholesterol and HDL

cholesterol and reserve for a full lipid profile only those persons

with a nonfasting total cholesterol greater than 200 mg/dL or an HDL

cholesterol less than 40 mg/dL (see Chapter 15).

|

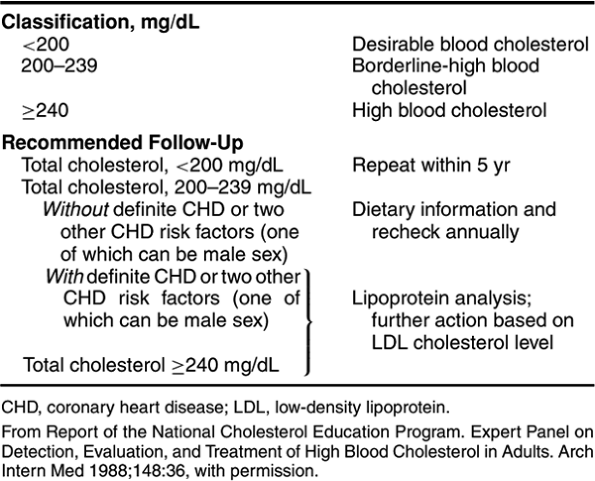

Table 27.2. Initial Classification and Recommended Follow-Up Based on Total Cholesterol |

Estimation of VLDL cholesterol and calculation of LDL cholesterol

are derived from measurements of total- and HDL-cholesterol levels and

the triglyceride concentration using the following formula:

LDL cholesterol = total cholesterol – (HDL cholesterol + triglyceride/5)

The triglyceride/5 factor represents a close estimate of

VLDL cholesterol and derives from the observation that VLDL cholesterol

is usually 20% of the serum triglyceride value. The validity of this

formula for estimating LDL cholesterol has been confirmed by direct

LDL-cholesterol measurement and remains fairly accurate so long as the

total triglyceride is less than 400 mg/dL. A fasting

sample is required for accurate results because chylomicrons appearing

in the blood after a meal do not contain the same ratio of triglyceride

to cholesterol found in VLDL. If the triglyceride level is greater than

400 mg/dL, the LDL cholesterol can be determined accurately only by

more sophisticated and expensive methods. These methods include

immunologic and nuclear magnetic resonance quantitation of LDL, gel

filtration techniques, and ultracentrifugation. The added cost of these

measures generally mitigates against their routine use, but they can be

useful in patients with elevated triglycerides or unusual clinical

presentations.

Excluding Secondary Causes

Before embarking on a treatment plan, one must exclude

conditions that might secondarily lead to hyperlipidemia. The most

important are hypothyroidism, nephrotic syndrome, and diabetes (Table 27.3), best screened for by a serum thyroid-stimulating hormone, urine dipstick for protein, and serum glucose, respectively (see Chapters 93, 104, and 130). Drugs can affect lipid levels as well, with LDL elevations occurring with thiazide use and triglyceride levels rising with beta-blockers. Postmenopausal estrogen replacement

lowers LDL and increases HDL and triglycerides. Antiviral protease

inhibitors used in the treatment of AIDS often cause hyperlipidemia as

well.

Table 27.3. Classification of Lipoprotein Disorders | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Classification

The original Fredrickson classification

scheme is of limited utility now that a better understanding of the

genetics of these diseases has emerged. However, no unified

classification of comparable simplicity has replaced it. For most

clinical purposes, it is probably simplest to separate patients into

three broad categories: those with elevated cholesterol, elevated cholesterol and triglyceride, and elevated triglyceride only. Table 27.3

summarizes the likely diagnoses under these broad categories. The

possibility of a genetic disorder should be considered if extremes of

any lipid level are encountered or if there is a history of premature

CHD in the patient or the family.

Risk Stratification

Risk stratification can be of considerable help to both

patient and physician, helping to provide an evidence-based rationale

for choice and intensity of treatment (see Tables 27.4 and 27.5).

Benefit from treatment of hypercholesterolemia is closely linked to the

degree of pretreatment CHD risk, making a careful assessment of that

risk essential.

Table 27.4. Coronary Heart Disease Risk Associated with Lipoprotein Cholesterol Abnormalities | |||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||

Table 27.5. Coronary Heart Disease Risk Factors and Coronary Heart Disease Risk Status | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

Role of Established CHD Risk Factors in Risk Stratification

The CHD risk assessment should be a comprehensive one,

including but also extending beyond lipid levels to consideration of

all major established risk factors, including hypertension,

smoking, diabetes, family history of premature CHD, age, gender, and

presence of established CHD or other atherosclerotic disease (e.g., peripheral arterial insufficiency, symptomatic carotid disease; see Appendix of Chapter 26 for calculation of risk). The increasing awareness of elevated HDL cholesterol as a factor in reducing CHD risk has led to its designation as a “negative risk factor”; conversely, a low HDL cholesterol

enters the list of positive risk factors (Table 27.5 and Appendix of Chapter 26).

P.194

enters the list of positive risk factors (Table 27.5 and Appendix of Chapter 26).

A gradient of CHD risk has been defined by the NCEP

expert panel, taking into account degree of LDL elevation and presence

of other CHD risk factors (Tables 27.4 and 27.5 and Appendix of Chapter 26). For a given elevation in LDL cholesterol level, patients can be additionally classified according to total CHD risk:

- Very high risk: acute coronary insufficiency or CHD plus multiple severe risk factors.

- High risk: established CHD or CHD risk equivalents (e.g., diabetes mellitus, peripheral or carotid atherosclerotic disease, multiple CHD risk factors with a 10-year CHD risk of >20%).

- Moderately high risk: no established CHD, but two or more CHD risk factors giving a 10-year CHD risk of 10% to 20%).

- Moderate risk: no CHD, but two or more CHD risk factors and 10-year risk less than 10%.

- Lowest risk: no CHD risk factors

Risk stratification by use of the established risk

factors does not fully account for all observed CHD risk. Efforts to

identify other independent risk factors are ongoing, with C-reactive

protein and homocysteine receiving the most attention.

Role of C-Reactive Protein in Risk Stratification

Epidemiologic evidence supports C-reactive protein (CRP) as an

independent risk factor for CHD events, particularly in women. However, the association between CHD risk and CRP elevation appears less pronounced than originally proposed (relative risk on the order of 1.5 vs previous estimates of 2 to 2.5) and weaker than that for the more established CHD risk factors. Moreover, there are no definitive data yet from long-term randomized clinical trials proving that lowering of CRP by itself reduces risk of CHD events, nor is it clear how to reduce CRP. Nonetheless, CRP determination may be helpful in selective instances where the results will change management of established treatable CHD risk factors (e.g., motivate the patient to make substantive lifestyle changes or trigger more aggressive pharmacologic treatment of modifiable CHD risk factors). If measured, the high-sensitivity assay for CRP should be used.

P.195

independent risk factor for CHD events, particularly in women. However, the association between CHD risk and CRP elevation appears less pronounced than originally proposed (relative risk on the order of 1.5 vs previous estimates of 2 to 2.5) and weaker than that for the more established CHD risk factors. Moreover, there are no definitive data yet from long-term randomized clinical trials proving that lowering of CRP by itself reduces risk of CHD events, nor is it clear how to reduce CRP. Nonetheless, CRP determination may be helpful in selective instances where the results will change management of established treatable CHD risk factors (e.g., motivate the patient to make substantive lifestyle changes or trigger more aggressive pharmacologic treatment of modifiable CHD risk factors). If measured, the high-sensitivity assay for CRP should be used.

Role of Homocysteine in Risk Stratification

Elevations in homocysteine are associated with statistically significant but modest increases in risk of CHD events (see Chapter 15).

Folic acid supplementation is capable of reducing elevations in

homocysteine, but there is no evidence yet from prospective, randomized

trials that reduction in homocysteine elevation reduces CHD risk.

Routine measurement of homocysteine levels is not warranted at this

time, but selective testing may be worth consideration when there is a

strong family history of CHD, onset of CHD is premature, or in the case

of a patient with CHD but no identifiable risk factors.

PRINCIPLES OF MANAGEMENT

Overall Approach (2,7,8,9,15,16,17)

The goals are to reduce coronary morbidity and mortality. Both primary prevention (reducing risk of having a first coronary event) and secondary prevention

(reducing risk of a new coronary event in a person with established

CHD) are sought. The most impressive reductions in risk are achieved in

patients at greatest risk (see later discussion), and the greatest

reductions are being increasingly realized with intensive lipid-lowering therapy in such persons.

The growing appreciation of the importance of lipid

abnormalities and the benefits of treating them have stimulated the

National Institutes of Health to sponsor the third formulation of the

ATP guidelines of the NCEP. Many of the treatment recommendations

generated by that expert panel are included here.

As noted earlier, the approach to treatment of hyperlipidemia is guided by an assessment of total CHD risk,

not just the lipid abnormality. For a given degree of LDL-cholesterol

elevation, the threshold for initiation of therapy decreases, and the

intensity of therapy increases with increasing CHD risk.

The NCEP treatment recommendations follow directly from

the degree of estimated CHD risk. Dietary modification is the sole mode

of therapy for patients at the lower end of the CHD risk spectrum,

whereas pharmacologic measures are reserved for patients at higher risk

or for those who fail dietary intervention (Table 27.6).

Additional considerations include possible adverse effects of long-term

pharmacologic therapy (an issue when dealing with young persons) and

appropriateness of the patient for treatment (an issue in the frail

elderly and seriously ill).

Table 27.6. Treatment Recommendations | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Dietary modification, complemented by exercise and

weight reduction, is the core of the lipid treatment program, with

pharmacologic therapy reserved for those at higher risk and for persons

failing behavioral therapies.

Dietary Modification, Exercise, And Weight Loss (4,6,9,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25)

Dietary modification remains the cornerstone of

treatment, effective for both treatment and prevention of

hypercholesterolemia. As suggested by the Hegsted equation (see earlier

discussion), the greatest contributor to hypercholesterolemia is

the consumption of saturated fat, with excess cholesterol contributing to a lesser extent. Reductions in total fat, saturated fat, partially hydrogenated unsaturated fatty acids, and dietary cholesterol are recommended for all adults. Not only is it important to reduce total fat in the diet, but perhaps it is even more critical to substitute foods that provide polyunsaturated and monounsaturated fats for those rich in saturated and trans unsaturated fat.

P.196

the consumption of saturated fat, with excess cholesterol contributing to a lesser extent. Reductions in total fat, saturated fat, partially hydrogenated unsaturated fatty acids, and dietary cholesterol are recommended for all adults. Not only is it important to reduce total fat in the diet, but perhaps it is even more critical to substitute foods that provide polyunsaturated and monounsaturated fats for those rich in saturated and trans unsaturated fat.

In conjunction with exercise and weight loss

(which contribute to reductions in lipid levels and ameliorate other

cardiac risk factors), dietary modification provides an excellent

nonpharmacologic means of improving the patient's lipid profile and

reducing CHD risk. The adverse effects are nil, making it the safest of

treatments for hypercholesterolemia and especially well suited for

persons with only a modest increase in CHD risk (e.g.,

hypercholesterolemic young men and premenopausal women with no other

CHD risk factors). Even for high-risk patients, diet is central to the

treatment program, having an additive effect when combined with drug

therapy.

Efficacy

Decreases in intake of cholesterol and saturated fat in

controlled settings can reduce total and LDL cholesterol by 15% to 30%,

but the reductions average about 10% when similarly intensive dietary

programs are prescribed for outpatient use. Although reductions in

total and saturated fat are important, substituting polyunsaturates and

monounsaturates for saturated and unsaturated fats appears to be as or

even more important in reducing CHD risk by dietary intervention. Data

from the Nurses' Health Study provide very encouraging estimates of

expected changes in CHD risk from various dietary substitutions:

- Substituting polyunsaturated fat for saturated fat: 42% decrease in CHD risk (for every 5% of total calories)

- Substituting polyunsaturated fat for trans unsaturated fat: 57% decrease in CHD risk (for every 2% of total calories)

- Substituting carbohydrate for saturated fat: 17% decrease in CHD risk

- Substituting carbohydrate for polyunsaturated fat and monounsaturated fat: 20% to 60% increase in CHD risk

Note that not all substitutions are beneficial. Simply

substituting carbohydrate for all fat might not be the best dietary

strategy for reducing CHD because beneficial polyunsaturates would also

be eliminated.

The net effects of various dietary substitutions are

related in part to their effects on CHD risk factors, including HDL

cholesterol, LDL cholesterol, triglycerides, lipoproteins, and

platelets and clotting factors. For example, substituting total fat

intake with carbohydrate may produce a small (approximately 5%)

reduction in HDL cholesterol, although the overall total-to-HDL

cholesterol ratio typically still improves. Caloric and fat

restrictions are also effective in lowering triglyceride levels, an

effect enhanced by prohibition of alcohol. Reductions in CHD risk

parallel the degree of cholesterol lowering and reduction of other risk

factors.

Response to dietary modification is determined to some

extent by the etiology of the hypercholesterolemia. When the phase I

diet (see later discussion) is prescribed for outpatient use in

patients other than those with monogenic hypercholesterolemia, the

total and LDL-cholesterol levels fall by 5% to 15%. Typically, the

total serum cholesterol level will fall to 140 to 160 mg/dL in normal

individuals consuming a very low fat (5% to 10% of total calories)

diet. More modest but still useful reductions can be expected from less

stringent diets. In the setting of a metabolic ward study, there is

wide variability in the magnitude of LDL-cholesterol reductions

achieved by lowering saturated fat intake, ranging from less than 5% to

greater than 50%. Patients with severe monogenic hypercholesterolemias

rarely respond to diet alone, whereas other individuals consuming a

high-fat diet may demonstrate marked benefit.

Phased Approach to Dietary Modification

The phased approach, as exemplified by the American

Heart Association's three-phase dietary plan, maximizes adherence.

Total fat, saturated fat, and cholesterol intake are gradually reduced

with partial replacement by polyunsaturated fats (which by the Hegsted

equation have a modest cholesterol-lowering effect). Excess dietary

saturated and trans unsaturated fats are

supplanted by use of polyunsaturated and monounsaturated fats and by

complex carbohydrates (fruits, vegetables, cereals, pasta, grains, and

legumes).

Phase I Diet

Given the high prevalence of undesirable cholesterol

levels in the U.S. population, it is recommended that all Americans

adopt the phase I diet (Table 27.7):

Table 27.7. American Heart Association Three-Phase Dietary Plan | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

- Total fat as a percentage of total calories is reduced to 30% from an average 40% to 45%

- Saturated fat is reduced to 10% of total calories

- Polyunsaturated fat is increased to 10% of calories

- Dietary cholesterol intake is reduced from 500 to 300 mg/d

- Protein is held constant

- The Ω-6 PUFAs found in vegetable oils should not exceed 10% of calories because they may lower HDL cholesterol

The phase I diet usually does not require a dramatic

alteration in eating habits and can be readily adopted by most persons.

It is important to note that much of the polyunsaturated fat found in

“low-cholesterol, low-fat” processed food products is usually partially

hydrogenated, converting otherwise beneficial vegetable oils into the

undesirable trans unsaturated

configuration. Such processed food products should not be considered a

substitute for saturated fat, but neither should saturated fat be

considered a healthier alternative to such products and trigger

reverting back to lard-based or tropical oil–based processed foods.

Phase II Diet

The phase II diet (Table 27.7)

entails more effort because it goes beyond eliminating the obvious

sources of fat and cholesterol. It is indicated for patients who do not

achieve adequate results with a phase I diet and for patients at

highest CHD risk (e.g., established CHD).

If just the phase I dietary interventions were widely

implemented, the overall incidence of CHD in the population would

probably drop significantly. The recommended percentages of fat intake

in the diet must be translated into real menus and food recommendations

if good compliance with these recommendations is to be realized. The

counsel of a dietitian is often beneficial, particularly if a phase II

diet is indicated. A good working knowledge of the fat content of

common foods is essential for patient, family, and health care team

(see Appendix III). A number of

“heart-healthy” cookbooks are on the market to help patients in their

food choices and preparation. The use of faddish cholesterol cookbooks

should be discouraged because these often do not promote sustainable

healthy eating habits. Increasingly, restaurants are offering low-fat

menu choices, and patients should be encouraged to select them.

P.197

Low-Carbohydrate Diets

The observation that high-carbohydrate intake can

stimulate weight gain and raise LDL cholesterol and triglyceride levels

has led to interest in low-carbohydrate diets. Unfortunately, the most

popular low-carbohydrate diets (e.g., the Atkin's diet) substitute

liberal amounts of saturated fat for carbohydrates. Although short-term

(6- to 12-month) studies of obese persons using such diets demonstrate

weight loss, reduction in triglycerides, and improved glucose tolerance

without a significant increase in LDL cholesterol, there remain

concerns about the long-term durability and cardiovascular safety of

the low-carbohydrate/liberal saturated-fat approach. More studies are

needed, including long-term trials and examination of modest

carbohydrate restriction in conjunction with limitations on saturated

fat.

Nonprescription Dietary Supplements

Nonprescription dietary supplements are no substitute

for dietary reduction in total fat, saturated fat, and cholesterol.

Nonetheless, they are popular with patients, even though they can be

expensive.

Omega-3 Fish Oils

Preliminary data from prospective studies of omega-3

fish oil supplements are encouraging, but they are too limited to serve

as the basis for dietary recommendations. Impairment of clotting has

been noted with use of high doses.

“Antioxidant” Vitamins

Vitamins C, E, and beta-carotene

(the so-called “antioxidant vitamins”) do not lower cholesterol levels,

but they are capable of increasing LDL resistance to oxidative change

and theoretically might reduce the risk of arterial wall injury. Data

from small-scale human studies of vitamin E suggested a possible

reduction in CHD risk, but early prospective, large-scale, randomized

trials have so far failed to confirm a significant benefit; the same

pertains to vitamin C. The typical dose of vitamin E used in these

studies is 400 to 800 IU/d. There is no evidence that beta-carotene

reduces CHD events, and some data suggest an association with lung

neoplasms; its use for CHD prevention is not recommended. More data on

vitamin E and C will be forthcoming and should further clarify their

value, if any, in preventing coronary events.

Garlic, Fiber, and Yeast Supplements

One-half to one clove of garlic

a day may produce a modest (5%) reduction in serum cholesterol, but

powder and oil preparations have not demonstrated consistent

significant benefit. Use of fiber preparations such as psyllium (10 g/d) also provides modest benefit, as does the soluble fiber in oat-containing cereals. Red yeast extracts

contain a cholesterol synthesis inhibitor that is a member of the

statin family and can lower LDL 10% to 15%. Alcohols contained in sugar

cane (policanosols) can reduce LDL cholesterol by 20% to 30%, but data

are needed on their safety and long-term efficacy.

Exercise and Weight Loss

ATP III emphasizes exercise and weight reduction as

complements to dietary therapy and essential components of a

comprehensive nonpharmacologic program. They are helpful not only in

correcting lipid abnormalities, but also in reducing other CHD risk

factors and total CHD risk. For example, exercise will raise the level

of HDL cholesterol, decrease blood pressure, and increase efficiency of

peripheral oxygen extraction (see Chapter 18). Weight loss efforts can lower fat intake, reduce risk of diabetes mellitus, and decrease myocardial work.

Pharmacologic Therapy: Principles (2,9,15,16,17,20,26)

Dietary modification is not uniformly effective in

achieving target reductions in LDL cholesterol or desired increases in

HDL cholesterol. Addition of drug therapy to a diet and exercise

program should be considered in high-risk patients whose lipid

abnormalities remain inadequately controlled despite intensive dietary

efforts. Use of lipid-lowering therapy in patients at lower levels of

risk has become increasingly common due to the publication of

large-scale trials showing impressive reductions in CHD morbidity and

mortality in patients without established coronary disease (i.e.,

primary prevention studies) and modest levels of hypercholesterolemia.

Many lipid experts are treating more aggressively than is recommended

by the ATPIII guidelines, using outcomes of studies published after the

guidelines were generated to justify this approach.

Effectiveness and Safety

The addition of drug therapy to a diet and exercise

program can greatly enhance lipid-lowering results and lead to

significant reductions in nonfatal and fatal cardiac events (i.e., myocardial infarction, revascularization, cardiac death). Reductions in all-cause mortality

have also been demonstrated in lipid-lowering drug trials, particularly

in higher-risk populations. With intensive drug therapy, the rate of

plaque progression falls, and modest plaque regression

can be demonstrated in major coronary vessels and systemic arteries.

There is now evidence that lipid-lowering medication (statins) also can

reduce risk of stroke in persons with atherosclerotic carotid disease.

The reductions in CHD events have been noted in patients with established atherosclerotic disease (secondary prevention),

who experience 30% to 40% reductions in coronary morbidity and

mortality. In addition, benefit also accrues to persons with no

clinical CHD and only moderate increases in CHD risk, whose reductions

in rates of fatal and nonfatal coronary events with use of

pharmacologic therapy (primary prevention) are on the order of 20% to 30%.

P.198

An early concern about an increased risk of cancer and

violent deaths with use of some lipid-lowering agents has failed to

materialize in major prospective, randomized, placebo-controlled

studies. In four of the largest such trials conducted to date, using

several different members of the statin class of drugs and collectively

involving tens of thousands of patients (the Scandinavian Simvastatin

Survival Study and West of Scotland, AFCAPS/TexCAPS, and LIPID

studies), no increase in rates of cancer or noncardiac deaths has been

reproducibly observed. However, each class of drug therapies has

important adverse effects that need to be taken into account when

considering pharmacologic intervention (see later discussion). With the

trend toward more aggressive lowering of LDL cholesterol comes an

increase in risk of drug side effects as larger drug doses are

prescribed.

Candidacy for Pharmacologic Therapy

The risk-to-benefit ratio for pharmacologic therapy

appears most favorable in patients at greatest CHD risk and least

favorable in those at lowest risk. Because most data derive from

studies involving middle-aged men and postmenopausal women with established CHD or multiple CHD risk factors,

one must extrapolate to estimate effects in other populations.

Treatment recommendations by NCEP are based on total CHD risk that

includes lipid profile and associated cardiac risk factors.

In the elderly, high CHD

risk is common. One might reasonably expect the benefit noted in

high-risk, middle-aged patients to accrue also to elderly persons at

similar risk. These expectations have largely been borne out in the

studies that have included large numbers of older individuals (Heart

Protection Study). Duration of therapy is less likely to be very

prolonged, lessening risk of an adverse effect from long-term use.

Young men (age <35 years) and premenopausal women

with no CHD risk factors other than hypercholesterolemia are best

considered for nonpharmacologic therapy because their short-term risk

of CHD is quite low, and the safety of very-long-term drug therapy is

not established. Because the first statin was approved for clinical use

more than 20 years ago, the concern over potential adverse long-term

treatment effects is rapidly diminishing. For young persons at greater

CHD risk (e.g., LDL cholesterol >220 mg/dL, potent CHD risk factors

such as diabetes mellitus, or strong family history of premature CHD),

the potential gain from use of lipid-lowering medication almost

certainly outweighs the speculative long-term risks, but there are no

outcomes data yet available to confirm this. However, in women of

childbearing age, the potential teratogenicity of statin therapy must

always be kept in mind when prescribing that class of lipid-lowering

agent. The exercise of good clinical judgment is essential in these

circumstances.

Pharmacologic Therapy: Available Agents (2,9,18,20,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41)

Design of a pharmacologic regimen must take into account the patient's degree of CHD risk, the nature of the lipoprotein abnormality, and a drug's mechanisms of action and side effects.

The best program is one that addresses and fits well into the patient's

overall clinical state. A large degree of individualization is

necessary. The range of available drugs is extensive, varying greatly

in cost, effect on cholesterol fractions, efficacy, and side effects (Table 27.8).

Table 27.8. Drugs Used to Treat Hyperlipidemia | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

3-Hydroxy-3-Methylglutaryl Coenzyme A Reductase Inhibitors (Statins)

These agents have become first-line drug therapy because of their effectiveness, patient acceptability, and

increasingly favorable safety record. They block the rate-limiting enzyme for cholesterol synthesis, 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme A (HMG-CoA) reductase. This inhibition decreases intracellular cholesterol and increases clearance of LDL. Serum LDL levels fall by 20% to 60%, depending on dose and preparation. They affect plaque regression, even when used alone. HDL levels generally stay the same or increase slightly (2% to 10%). Statins also influence thrombotic and inflammatory mechanisms, effects whose importance remains to be proven but may account for some of the surprising CHD prevention efficacy seen in persons with lower LDL-cholesterol levels (see later discussion).

P.199

increasingly favorable safety record. They block the rate-limiting enzyme for cholesterol synthesis, 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme A (HMG-CoA) reductase. This inhibition decreases intracellular cholesterol and increases clearance of LDL. Serum LDL levels fall by 20% to 60%, depending on dose and preparation. They affect plaque regression, even when used alone. HDL levels generally stay the same or increase slightly (2% to 10%). Statins also influence thrombotic and inflammatory mechanisms, effects whose importance remains to be proven but may account for some of the surprising CHD prevention efficacy seen in persons with lower LDL-cholesterol levels (see later discussion).

Cost and Cost-Effectiveness

Cost and cost-effectiveness are important considerations

in selecting statin therapy because all these agents are expensive and

use is likely to be measured in years. Although fluvastatin has usually

been the least expensive and pravastatin and simvastatin the most

expensive of the statins, cost often depends on specific pricing

contracts with large payers, making generalizations difficult.

Lovastatin is now available as a generic agent, and simvastatin will

transition to that status in 2006, making it likely that some downward

cost pressure will be imposed on the whole class. The statins differ

principally in cost and potency, which often parallel one another. Cerivastatin

was removed from the market in the summer of 2001 because of high

adverse event report rates of myositis and rhabdomyolysis, particularly

when used in combination with gemfibrozil. Simvastatin, atorvastatin, and rosuvastatin

are the statins that give the greatest LDL-cholesterol reduction at

U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA)–approved dosing levels. Within

this group of three, the rank order of LDL-cholesterol–reducing

activity is simva < atorva < rosuva. LDL reductions of 50% to 65%

can be achieved with these drugs.

Although the major drawback to statin use is cost, cost

savings from reduced rates of cardiac events, time lost from productive

work, and premature death at least partly offset the high cost of

treatment. Formal cost-effectiveness analyses are appearing in the

literature. Data from the Scandinavian Simvastatin Survival Study

examined cost per year of life gained and found statin therapy

cost-effective in men and women over a broad spectrum of ages and

cholesterol ranges. The cost per year of life gained was less than half

of that for other cost-effective preventive measures such as

mammography.

Dosing

Starting dose for these agents is typically 10 to 20

mg/d, with the more potent drugs started at the lower dose. The maximum

dose is currently 80 mg/d for lovastatin, simvastatin, fluvastatin,

atorvastatin, and pravastatin. The maximum dose of rosuvastatin is 40

mg/d. The shorter-acting agents are best taken at night, the time of

peak cholesterol synthesis, but all drugs work satisfactorily even if

taken once daily in the morning.

Adverse Effects

Asymptomatic hepatocellular dysfunction

manifested by an increase in serum levels of hepatocellular enzymes

(e.g., aspartate and alanine aminotranferases) is among the most common

adverse effects. Incidence ranges from about 3% for any elevation to

less than 1% for elevations greater than three times the upper limit of

normal. All such increases are reversible with cessation of therapy,

which should be considered when liver enzyme levels continue to rise or

reach more than three times the upper limit of normal. Transaminase

monitoring is strongly recommended, with initial measurements made

after 1 to 2 months of therapy, and follow-up measurements made at 6

months and 1 year. The lack of new onset of liver toxicity after 1 year

of therapy has led many to advocate limited monitoring after 1 year.

Harmless elevations in muscle enzymes

(e.g., creatine phosphokinase <10 times the upper limit of normal)

occur in about 0.6% of cases and require no action in an asymptomatic

patient. Myalgias without creatine phosphokinase elevations also occur

with statin use, making routine monitoring of creatine phosphokinase of

limited value. Myalgias are probably underreported in patients on

statins, particularly in the elderly, because the symptom is frequently

attributed to arthritis or muscle stiffness associated with the aging

process. Patients should be questioned about increased muscle

discomfort when placed on statins, and drug holidays may need to be

instituted to clarify complaints. Symptomatic myositis

with demonstrable muscle breakdown is much less common, but the risk is

increased with high-dose therapy and when other lipid-lowering agents

are used in conjunction with statin therapy. Statin monotherapy has

been reported to cause rhabdomyolysis and renal failure, but it is more common in the setting of concurrent gemfibrozil

use. Dual therapy with niacin can also increase myositis. Joint use of

a statin and a fibrate (either gemfibrozil or fenofibrate) should be

done only with great caution and probably only by a lipid specialist.

Because of an FDA warning against this combination, pharmacists will

often not fill a prescription that places a patient on both drugs

without first calling the physician. The withdrawal of cerivastatin

from the market in 2001 was prompted by many reports of rhabdomyolysis

when the drug was used alone or, more commonly, in combination with a

fibrate. This event will likely increase the vigilance of pharmacists

in responding to combination-therapy prescriptions.

As noted earlier, initial concerns about an increase in

non-CHD mortality (e.g., from cancer, suicide, or violence) were raised

by early meta-analyses, but large-scale prospective studies of statins

show no evidence for such adverse effects.

Choice of Agent

Although most experts believe that all of the statins

will reduce coronary events in proportion to their efficacy in lowering

LDL cholesterol, not all statins have been proven to do so. The best

studies of clinical outcomes have been performed using simvastatin,

pravastatin, and lovastatin, but atorvastatin also has been found to

reduce cardiovascular event rates. Prospective studies with statins

have not only demonstrated a reduction in coronary events, but they

have also been shown to lower all-cause mortality. Patients who require

modest reductions in LDL cholesterol (25% or less) can be started on

any of the statins with the expectation that the reduction will be

achieved. Those with marked LDL elevations and high overall CHD risk

require more intensive therapy (>40% reductions) and are better

served if started on the more potent statins.

Niacin

This B vitamin contributes to dyslipidemia therapy by virtue of its unique ability to markedly raise HDL cholesterol

(on the order of 15% to 35%). Its purported mechanism of action

involves inhibiting mobilization of free fatty acids from fat tissue to

the liver. The substance also lowers triglycerides (by 20% to 50%) and LDL cholesterol

(by 5% to 25%), converting small LDL-cholesterol particles to more

bouyant less atherogenic forms. Use in high-risk persons (e.g., prior

myocardial infarction) has been associated with significant reductions

in new myocardial infarction (26%), stroke (24%), and death (11%).

Niacin in combination with colestipol or a statin has produced documented regression of atheromatous plaque in coronary

arteries. Although effective, niacin therapy often requires high doses (1.5 to 3.0 g/d) to achieve the desired results. Use in combination with a statin (which can also raise HDL cholesterol) may allow for somewhat lower doses.

P.200

arteries. Although effective, niacin therapy often requires high doses (1.5 to 3.0 g/d) to achieve the desired results. Use in combination with a statin (which can also raise HDL cholesterol) may allow for somewhat lower doses.

Adverse Effects

A high-capacity, early route of niacin metabolism involves conjugation with glycine to produce nicotinuric acid, which produces flushing,

the immediate and principle side effect that limits clinical use.

Tolerance to flushing develops over time and allows slow advancement of

dose. The bothersome side effect can also be lessened by starting with

a low dose (e.g., 100 mg thrice daily), using an extended-release

preparation (see later discussion), taking once-daily pretreatment with

a nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drug (e.g., aspirin 325 mg, or

ibuprofen 200 mg, 30 to 30 minutes before first dose), and taking

niacin with meals.

Hepatotoxicity is the other

major concern, related to nonconjugative metabolism of the drug to

nicotinamide and pyrimidines. Risk of hepatotoxicity is greatest with

use of sustained-release preparations (18

to 24 hours' duration), which are metabolized predominantly by the

nonconjugative route. Risk is minimized by taking an intermediate

(“extended”)-release formulation (8 to 10 hours' duration), which

optimizes metabolism through both pathways. Periodic monitoring of

liver function (e.g., aspartate aminotransferase determination) is

required with niacin use.

Other adverse effects include exacerbation of gout and slight worsening of glucose intolerance, necessitating an occasional check of uric acid and glucose. Rashes, dry skin, and occasionally acanthosis nigricans

may accompany niacin use. Lanolin cream helps the former, and prompt

cessation clears the latter. Some patients experience gastrointestinal

upset.

Preparations

As a B-complex vitamin (nicotinic acid), niacin is available without prescription in immediate-release and sustained-release

forms. Although least costly, these are associated with the highest

frequency of flushing and hepatotoxicity, respectively. A prescription

is required for the intermediate-release preparation (also referred to as extended-release

niacin [e.g., Niaspan]), which is the best tolerated but most expensive

formulation. Its use should be considered in persons who cannot

tolerate the immediate-release preparation or in whom there is concern

about risk of hepatoxicity. If an inexpensive, well-tolerated,

immediate-release brand of niacin is found, the patient should stay

with it; changing brands might not be as well tolerated.

Bile Acid Sequestrants (Cholestyramine, Colestipol, Colsevelam)

These nonabsorbable agents have been first-line

pharmacologic therapy for many years, with an established record of

safety. They are very useful for patients who are not at great CHD risk

but in whom diet alone fails to lower LDL cholesterol to target levels.

They are also of benefit in individuals who are statin intolerant.

Though not as cost-effective as the statins or niacin, they are very

effective when used in combination with them to treat high-risk

patients with severe hypercholesterolemia. The sequestrants bind bile

acids in the gut and interrupt their normal enterohepatic circulation.

The resultant shunting of cholesterol in the liver to bile acid

production leads to a fall in total- and LDL-cholesterol levels.

However, triglyceride levels often rise with this class of drugs,

particularly if moderate hypertriglyceridemia antedates the initiation

of the therapy. Cholestyramine and colestipol are prescribed as powders

that are dissolved in liquid. Colesevelam, which comes as a 625-mg

pill, also binds biliary lipids in the gastrointestinal tract and has

comparable effects on the serum cholesterol.

Adverse Effects

The bile sequestrants are nonabsorbable resins whose major side effects are gastrointestinal—constipation, bloating, heartburn, and nausea.

A high-fiber diet or psyllium supplement and use of these agents just

before a meal will usually ameliorate the gastrointestinal upset. The

potential to impede absorption of certain drugs

(e.g., digoxin, thyroxin, warfarin, tetracycline, phenobarbital)

necessitates that bile sequestrants not be taken until at least 1 hour

after or 4 hours before these other drugs. In rare instances,

steatorrhea and malabsorption of the fat-soluble vitamins (A, D, E, and

K) can occur. The usual starting dose is one scoop of the powdered form

of the drug (4 g of cholestyramine, 5 g of colestipol) in a large glass

of water twice a day. Dose can be increased to a total of three scoops

twice daily. A newer formulation of cholestyramine, which is

significantly less gritty (Lo-Cholest), can be tried if the texture of

the generic drug formulation should prove unacceptable. Colesevelam is

given as six 625-mg tablets a day, given in once-a-day or twice-daily

dosing.

Ezetimibe

Ezetimibe is a new agent that, like the bile acid

sequestrants, blocks cholesterol absorption from the gut. Unlike the

sequestrants, however, ezetimibe is postulated to inhibit cholesterol

transport by interfering with a specific transporter protein required

for this activity rather than interfering with micellar solubization of

lipid. This difference permits ezetimibe to be given in milligram doses

rather than gram doses, and it does not interfere with the absorption

of other drugs and fat-soluble vitamins. The ease of use and

tolerability of ezetimibe have led to its use in many of the

circumstances where bile acid sequestrants were formerly used. As a

single agent, ezetimibe lowers LDL cholesterol by 15% to 20%. When used

in conjunction with a statin, it typically provides an additional 15%

reduction in the LDL-cholesterol level.

Estrogens

In postmenopausal women, estrogen replacement therapy is effective in lowering the levels of LDL cholesterol and raising those of HDL cholesterol.

These changes would be expected to reduce coronary events, and

retrospective analyses of hormonal replacement therapy initially

confirmed this expectation, but several large-scale, prospective,

randomized trials of estrogen therapy or estrogen plus progestin failed

to demonstrate any benefit in reducing cardiovascular morbidity or

mortality. The Women's Health Initiative study was prematurely ended in

2002 when the rate of invasive breast cancer in the

estrogen–progestin-treated group exceeded the stopping boundary for

this condition. No benefit on cardiovascular status was seen in the

hormone-treated cohort. The estrogen-only arm of the same trial was

terminated in 2004, again with no benefit on CHD morbidity or mortality

detected. Thus, despite the beneficial impact on serum lipids, hormone

replacement therapy has failed to produce improved cardiovascular

outcomes and can no longer be recommended as a standard therapy for the

prevention of CHD.

Fibrates (Gemfibrozil and Fenofibrate)

Because these drugs lower LDL cholesterol much less

effectively than the statins, they are not considered first-line drugs

for the treatment of hypercholesterolemia. Nonetheless, they do have

specific uses. They decrease VLDL synthesis and enhance its clearance. They also raise HDL cholesterol, most prominently in

those who have concomitant triglyceride elevations. The effect on LDL cholesterol is variable, although an 8% to 15% reduction can be seen in patients who do not have markedly elevated VLDL levels.

P.201

those who have concomitant triglyceride elevations. The effect on LDL cholesterol is variable, although an 8% to 15% reduction can be seen in patients who do not have markedly elevated VLDL levels.

Both fibrate agents are generally well tolerated, but

they can increase bile cholesterol content, raising the risk of

gallstone formation and potentiating the effect of warfarin. The FDA

has issued a warning about their use in combination with statins

because rhabdomyolysis has occurred when

gemfibrozil and a statin are used concurrently. An earlier drug in this

class, clofibrate, was taken off the market because of reports of increased mortality

associated with its use. Although the FDA has approved both fibrates,

these agents have yet to demonstrate a reduction in all-cause

mortality. A Veterans Administration gemfibrozil study of men with low

HDL cholesterol did show improvement in coronary outcomes; HDL

cholesterol rose, triglycerides fell, and LDL cholesterol stayed the

same.

Pharmacologic Therapy: Treatment Thresholds, Goals, and Monitoring (2,5,9,17,20,26,35)

Treatment Thresholds

Current guidelines derive from the evidence-based

consensus recommendations of the NCEP panel and reflect the trend

toward lower LDL-cholesterol thresholds for treatment in persons at

increased risk. Recent major clinical trials have shown improved

outcomes using low LDL cut-points.

For Those at Very High Risk (e.g., Acute Coronary Insufficiency or CHD plus Multiple Severe Risk Factors)

The newest revisions recommend an optional LDL-cholesterol treatment threshold of 100 mg/dL, with a goal of less than 70 mg/dL.

For Those at Moderately High Risk (No CHD, but Multiple Risk Factors and 10-Year CHD Risk of 10% to 20%)

The LDL-cholesterol treatment threshold has been lowered to 130 mg/dL, with a treatment goal of less than 100 mg/dL.

For Those at Moderate Risk with Two or More CHD Risk Factors (Two or More Risk Factors, 10-Year Risk Probability Is <10%)

The threshold for persons in the lower-risk categories

remains unchanged from previous recommendations. For this group the

LDL-cholesterol cut-point continues to be 160 mg/dL.

For Those with Fewer Than Two CHD Risk Factors

Drug therapy is definitively recommended for LDL-cholesterol levels above 190 mg/dL and considered optional for those with values between 160 and 190 mg/dL.

For Those with Isolated Low HDL Cholesterol

Although epidemiologic data show a strong inverse

relation between HDL level and CHD risk, there are no data yet from

large-scale, randomized, prospective clinical trials showing that

raising HDL cholesterol alone significantly reduces CHD mortality.

However, treatment of patients with low HDL levels with statins does

seem to lower CHD morbidity. Generally, healthy middle-aged and elderly

persons with low HDL cholesterol and “normal” LDL cholesterol

demonstrate a significant reduction in risk of a first acute major

coronary event (e.g., myocardial infarction, unstable angina) when

treated with a statin drug (e.g., the AFCAPS/TexCAPS trial). Such

findings suggest that even persons with modest increases in CHD risk—as

manifested by advancing age and an isolated low HDL cholesterol—might

benefit from pharmacologic therapy. The mechanism of the benefit may be

other than the effect on HDL cholesterol because in the AFCAPS/TexCAPS

study, HDL cholesterol rose only 6%.

Effect of Threshold on Cost-Effectiveness

Lowering the threshold for drug therapy below that

recommended by the new NCEP guidelines could be justified on the basis

of recent outcome studies, but the cost-effectiveness of such an

approach remains to be established. Because results are typically

reported in terms of reduction in relative risk, the magnitude of the

benefit to lower-risk patients may sometimes appear inflated. Absolute

risk certainly becomes an issue in younger patient populations, where a

20% to 30% reduction in relative risk may represent only a modest

clinical achievement (i.e., if the absolute risk of having a CHD event

over the next 10 years is only 2%, a 20% reduction results in the

absolute risk falling to 1.6%).

Treatment Goals

The ultimate treatment goal is reduction in CHD risk; the immediate one is reduction of LDL cholesterol. Target levels have been lowered, reflecting the improvement in outcomes associated with lower LDL-cholesterol levels. For primary prevention (no established CHD), the NCEP target is an LDL-cholesterol level less than 130 mg/dL, although ATP III now defines an optimal LDL cholesterol as less than 100 mg/dL and sets an optional LDL cholesterol target of less than 100 mg/dL for persons with moderately high CHD risk (estimated 10-year risk 10% to 20%). For secondary prevention (established CHD), the goal is an LDL-cholesterol level less than 100 mg/dL with an optional goal of less than 70 mg/dL for persons at very high risk.

The latest NCEP guidelines introduced the concept of elevated non-HDL-cholesterol

levels. Non-HDL cholesterol is determined by subtracting the

HDL-cholesterol value from the total-cholesterol value. Patients with

high triglyceride levels will have elevations in their VLDL

cholesterol, which in turn contributes to a higher non-HDL cholesterol

level. ATP III suggests for patients with high triglyceride levels

substituting a non-HDL-cholesterol goal in place of the LDL-cholesterol

goal and setting the cut-point 30 mg/dL higher than the LDL cut-point.

The rationale is that the calculated LDL may not be accurate in

patients with high triglycerides. This 30-point differential derives

from the Friedewald formula, where VLDL cholesterol is represented by

the triglyceride value divided by 5 (i.e., 150/5 = 30). So, as the

triglyceride level rises above 150 mg/dL, the VLDL contribution to the

non-HDL cholesterol will rise above 30 mg/dL.

Monitoring

This is performed by measurement of the LDL-cholesterol

level, beginning about 6 to 8 weeks after initiation of therapy and

then every 3 to 4 months until control is established. Afterward, every

6 to 12 months is usually sufficient. More-frequent monitoring for

development of abnormalities in serum chemistries (e.g., liver enzymes)

is indicated when using certain pharmacologic agents (see prior

discussion).

Treatment in the Elderly (9,16)

Prevalence of hypercholesterolemia is greatest in those

older than 65 years of age. As in other age groups, elevations in total

and LDL cholesterol are predictive of increased cardiovascular risk.

However, the statistical risk relationship is not as strong as in

younger patients due in part to the frequent occurrence of other

important risk factors in the elderly (e.g., diabetes, hypertension).

Elderly patients may have other advanced diseases, making prevention of

coronary disease appear irrelevant to their overall quality of life. In

those who are vigorous and have a considerable life expectancy,

however, primary and secondary prevention of CHD can be very important.

P.202

Several factors favor treatment. Life expectancy

continues to lengthen, and the quality of life in the elderly also has

steadily improved. Treating individuals in their late 60s and 70s with

statins has been shown to reduce CHD and stroke, two of the major

causes of mortality in that age group. The elderly are more likely to

have preexisting CHD, and the benefits on secondary prevention of

coronary disease by lowering cholesterol exceed the benefits of primary

prevention. With the advent of better tolerated cholesterol-lowering

medications, the risks of adverse effects and their negative impact on

quality of life have declined. All these factors combine to make the

recommendation to treat hypercholesterolemia in the elderly quite

appropriate.

Dietary Measures

Dietary therapy of hypercholesterolemia in the elderly

is similar to that for all adults and should be carried out as the

first step in treatment, though dietary measures do not always suffice

by themselves. Carbohydrate should not replace most fat in the diet,

rather polyunsaturates and monounsaturates should be increased. The Ω-6

polyunsaturated fatty acids found in vegetable oils should not exceed

10% of calories. For the elderly, modifications of the usual

low-saturated-fat diet are needed to ensure adequate calcium intake for

prevention of osteoporosis. Use of skim milk and low-fat and nonfat

yogurts are examples of ways to maintain calcium intake while cutting down on saturated fat. Maintaining adequate protein intake

is also essential, meaning that lean cuts of red meat ought to be

allowed in addition to fish and skinless chicken to ensure palatability

of the diet. High fiber is essential for good bowel function and cannot hurt the cholesterol-lowering effort.

Pharmacologic Therapy

Because dietary therapy alone frequently fails to

achieve the goal of an LDL cholesterol lower than 130 mg/dL, drug

treatment must often be considered.

Statin therapy is indicated

when aggressive lowering of LDL cholesterol is needed. The statins have

also proven useful for primary prevention in elderly persons with low

HDL cholesterol and average LDL cholesterol. These drugs are well

tolerated in the elderly, with minor diarrhea, myalgias, and occasional

sleep disturbances being the most common problems. Minor transaminase

elevations are common; they are usually asymptomatic and not a cause

for discontinuation unless they exceed three-times normal. However,

regular transaminase monitoring is required throughout the course of

therapy. As noted earlier, initial concerns about an increased risk of

malignancy have proven unfounded in large-scale, prospective, long-term

follow-up studies. Statins are recommended as first-line drug therapy

for hypercholesterolemia in the elderly.

The bile sequestrants are

safe but can cause considerable gastrointestinal upset, especially

constipation. Increasing dietary fiber helps. Because sequestrants can

impair drug absorption, their use in elderly patients must include

instruction to take other medications at least 1 hour before or 4 hours

after sequestrant use. Among the drugs that might be affected by

sequestrants are warfarin, propranolol, digitalis preparations,

thyroxin, and antibiotics. Although low-dose sequestrants are a

reasonable first choice for pharmacologic therapy, the availability of

ezetimibe has provided a better tolerated alternative to statins.

Niacin is effective,

although not always well tolerated. Its advantages over statins are its

ability to also raise HDL cholesterol and its low cost. The incidence

of side effects in the elderly is high, with flushing, gastrointestinal

upset, dry mouth, and dry eyes being particularly annoying. The drug

may exacerbate peptic ulcer disease, elevate transaminases, and trigger

arrhythmias and hypotension. Multiple daily doses are usually required

if the nonprescription forms are used. The once-daily formulation of

niacin, Niaspan, has some distinct advantages but is associated with a

higher cost than the nonprescription formulations.

PATIENT EDUCATION (6,9,25)

Regarding Diet and Exercise

The importance of patient education in the management of

hyperlipidemia cannot be overemphasized because treatment starts with

alterations in the patient's eating and exercise habits (see Chapters 18 and 233).

The first step in therapy should be a careful review of the rationale

for treating hypercholesterolemia, followed by a discussion of basic

dietary principles for lowering cholesterol. Consultation with a

dietitian can be very helpful. Many patients are surprised to learn

that dietary fat is more atherogenic than dietary cholesterol itself

(witness the patient who eats cholesterol-free potato chips with

abandon). Reviewing the saturated fat and trans

fat content of foods regularly consumed by the patient is quite

worthwhile. At times, simply removing a few grossly offending foods

from the diet (e.g., processed snack foods, cheese, grossly fatty

meats, cold cuts, fried food) will ensure a good start to a change in

eating habits. More comprehensive diet planning can be aided by

discussion with the nurse or dietitian, facilitated by written material

such as that produced by the American Heart Association. Periodic

visits to check diet, weight, and cholesterol are excellent, although

often overlooked, means of facilitating compliance and providing

reinforcement.

Regarding Medications

Patients need to understand the rationale for their

medical program and the details of its proper use and side effects.

Some mistakenly believe their drug program is curative and stop

treatment after a few months of therapy. Others harbor exaggerated

concerns about adverse drug effects and stop medication prematurely.

Cost is another factor that often limits compliance, necessitating a

strategy that takes into account the patient's insurance coverage for

medication. However, careful studies find that adequacy of insurance

does not by itself explain the nearly 40% fall-off in compliance that

occurs over 5 years among patients prescribed lipid-lowering

medication. Choice of agent, comorbidity, and socioeconomic status also

play important roles, underscoring the importance of comprehensive and

ongoing patient education.

INDICATIONS FOR REFERRAL

To the Dietician

Patients prescribed a dietary program should have a consultation with a dietitian

if they are unclear about the food choices they should make or if

compliance with the diet is problematic. Dieticians can provide

educational materials, food preparation advice, and the periodic

feedback that patients often need to permanently change their eating

habits.

To the Lipid Specialist

Patients with high-risk lipid profiles who do not

respond to diet plus one or two first-line drugs, those with extremes

of any lipoprotein level, or a family history of premature coronary

disease (before age 55 years) should be considered for referral to a

physician expert in diagnosis