Jason Flahardy

Science Fiction In The Library Environment

Science fiction has gained respectability in academic circles, and research is often hampered by the lack of primary and even secondary source materials. Primary source material for research into science fiction is often woefully deficient, and secondary source materials, in the form of commercially printed works, are also scarce. Mostly the researcher must gather his or her own secondary source materials in the form of novels and short story collections, lurking in the dusty confines of used book shops and acquiring substandard editions.

It is rare when a university archives (or academic or public libraries, for that matter) make it even a dim priority to collect, maintain, or properly preserve a body of science fiction suitable for research purposes. This is compounded by the general disinterest in science fiction and the preservation challenges that science fiction poses for public and academic libraries.

The first, and possibly most damaging blow to science fiction research collections, is the genre bias against science fiction. Science fiction is still perceived as a genre mainly appealing to teenage boys and asthmatic adults dressed as Klingons. This bias plays out in the minds of librarians and archivists by science fiction being considered largely undifferentiated and disposable. Therefore there exists in some public and academic librarian professionals a blasé contempt for science fiction. Unless a genre enthusiast happens to have some input on the selection and collection of science fiction works, this often results in the purchase of popular quasi-forms of science fiction, rather than the small body of "literary" works that would probably hold more interest for researchers.

Another problem driven by genre bias is weeding. Science fiction is often hit hard during weeding projects driven by circulation statistics. The low readership of "literary" science fiction in libraries may be a feedback loop, wherein libraries have never provided material of that nature, therefore interested parties stay away, causing the circulation statistics to be low, prompting little of it to be bought. Also, weeding is occasional done on looks alone, and many science fiction works have garish, cartoonish covers, prompting indifference, if not contempt. Because of the undifferentiated nature of the genre when viewed by people who have little interest in it, an attitude of "this one is as good as the next one," so older work loses out to newer work that seems "fresher."

Preservation Challenges

If science fiction works manage to survive selection and retention in either public or academic library environments, there are other hurdles for them to cross before they become available to future researchers. The genre bias can be said to work in reverse also and this manifests itself in the physical construction of the works themselves. This creates a host of inherent vices.

Few science fiction novels before 1960 were published in hardcover, and even after the practice became widespread, hardcover print runs were small, devoted to mostly a library environment or book club editions. Library hardcover editions are vulnerable to weeding but generally hold up physically. Book club editions often use the same typesetting of the "first" hardcover print run, but are generally on much lower quality (mid to high acid content) paper and given stab stitching, which leaves the binding very susceptible to disintegration.

The most common form of publication, and often the most widely bought, is the paperback. The paperback has a long tradition in science fiction and it (along with mysteries) has survived the recent industry effort to replace the paperback with the larger, more expensive, but cheaper to produce trade paperback. Unfortunately, the paperback is not a durable format. Like manuscripts, insects and rodents can attack them easily. The paper cover leaves it quite vulnerable to water and other fluids. The cover is also glued rather than stitched. Many covers come off paperbacks after just a few decades, a blink of an eye in archival terms.

Quality books can be produced, but often the money is not spent on what is seen as a disposable format and subject field. Paperbacks from the 1950s and 1960s--some of the most important works in terms of the current phase of science fiction studies--often do not have a corresponding hardcover publication. Even oft-reprinted works may never have appeared in any form except high-acid content paperback editions, essentially "pulps."

Due to the fragile nature of the materials, secondhand science fiction is often in a sorry state indeed. The popular bias of the basement dwelling science fiction fan moves from stereotype to reality when a collector is faced with a previously waterlogged paperback swollen to twice its original thickness or the long-sought 1950s-era short story magazine that has had all four corners nibbled by an industrious mouse.

The availability of the texts has a related issue: the research potential of the covers and bindings themselves: how those bindings and manufacturing processes change over the evolution of science fiction and the covers regarded as works of art in their own right. These issues suggest that science fiction may be a type of medium rare binding, which impacts the preservation perspective conservationist should take with them.

Science Fiction Bindings: Art and Advertising

For a popular genre such as science fiction, front cover art and back cover synopsis is an important advertising medium. Almost all books use cover art and back cover (or dust jacket flap copy) to advertise; science fiction existed for years as a genre that is not widely reviewed. Reviews are important to fiction of all types as a way to preview literary works one might wish to purchase. Even now, only hardcore fans make the effort to seek out the few reviewing bodies for advance book publication information.

Therefore, much of science fiction, especially before the 1970s, was an impulse buy. Cover art and copy becomes the only synopsis and review available to the audience. So-called blind purchase of science fiction leads to lively, sometimes strange, and often disastrous results:

Edition inconsistencies: Editions are often changed radically at the

publisher's insistence for the dubious reason of public appeal. Philip K. Dick's

The Unteleported Man (1966) was published in four different reprint editions

with 15,000 words unceremoniously excised by the publisher, Ace. The original

text was restored in a 1983 Berkley edition with four missing pages left blank;

a new first chapter (written by Dick before his death) appeared in a Gollancz

British edition in 1984 under the title Lies, Inc. The four missing pages

were eventually published in an edition of The Philip K. Dick Society Newsletter

in 1985. (Sutin, 304)

In the 1952 Dell mass market paperback editon of Wilson Tucker's The Long, Loud Silence (1952), the protagonist is a veteran of the Korean War. In the 1969 Lancer paperback, he is changed to a Vietnam veteran, but only superficially. The novel is not redacted to the point of placing the entire novel in 1969; only the status of the protagonist in changed. The novel still takes place in 1952, according to the dress, speech patterns, and social climate of the characters.

The popularity of the paperback format: A time-proven way to encourage impulse buying is by keeping the unit price low. A reader is much more likely to blind purchase a book with little or no review or preview if the financial risk is minimal. The best way for the publishers to minimize unit price and maximize profit is to construct books in the cheapest manner possible. This leads to the science fiction paperback. Most are burst or hot glue bound and printed on cheap, high-acid paper. Mass market paperbacks are very unsuited for a circulating library environment. The spines crack easily, shedding pages like fall leaves. The covers scuff and are very water sensitive. Tight margins keep printing costs low, but hamper rebinding. Even double fan adhesive rebinding and casing into buckram covers is often ineffective due to poor paper quality. And unless the covers are carefully preserved, the character and flavor of the cover art can be lost.

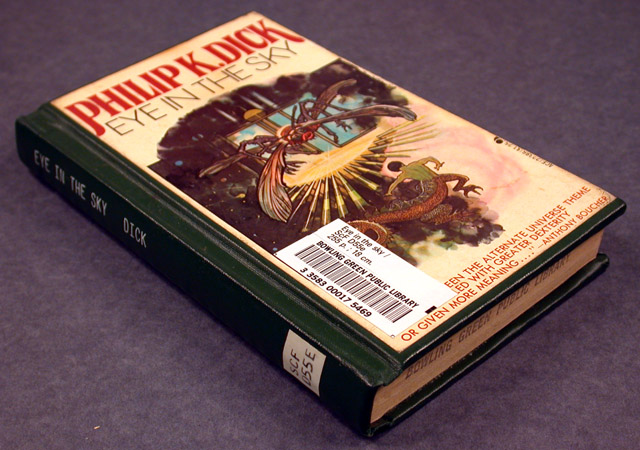

Philip K. Dick, original and library bound editions of Eye

in the Sky, Ace Books, 1975.

The text on the back cover was not preserved on the bound edition.

Changing cover art: One of the most powerful arguments for viewing science fiction paperbacks as a medium rare binding is the ever rotating cover art of reprint editions. Very rarely do editions, sometimes only a few years apart, carry the same cover art. And as all art reflects the culture that created it, even and sometimes especially commercial art, it is quite revealing. Science fiction cover art can tell the tale of how science fiction is viewed by the people who produce it, consume it, dismiss it, and misunderstand it.

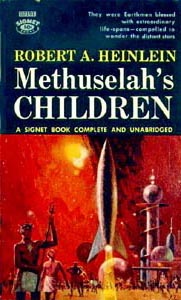

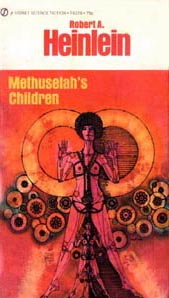

Robert A. Heinlein was at the forefront of science fiction writers in 1955 when Methuselah's Children appeared collected in paperback. All of his available work was selling well, and many of those works were fitting into a cogent fictional universe eventually to be called his "Future History" series (1), but the keystone of the series, Methuselah's Children, had only seen a serialization in Astounding Science Fiction in 1941. The story is set in 2136 and concerns the Howard Families, a group of long-lived human beings facing prejudice on Earth. Humans with normal lifespans assume that the "Howards" have a technological secret they are refusing to share, when really their longevity is a result of careful, scientific intermarriage. The Howards, with Lazarus Long as their leader, decide to escape persecution and eventual vivisection on Earth by stealing the only interstellar ship in the solar system. Methuselah's Children was expanded and issued in 1958 in paperback by Gnome Press and then widely distributed in 1962 by Signet in mass market paperback.

Signet, 1962: This cover is fairly typical of the period. Only the rocket is highlighted and it is set among a vague, stylized "spaceport." There is little attempt to visualize what a real interstellar vehicle might look like (even at the time, engineers realized that such a vehicle could only be constructed in the weightless environment of high orbit and could never land or take off of a planetary surface) and the artist basically renders a Nazi V2 rocket painted silver.

Signet, 1970: Mostly likely reprinted in the wake of the popularity of Heinlein's Stranger in a Strange Land (1961). Stranger was a bestseller and a cult hit with the youth counter culture movement starting in 1968, and the Signet reprint reflects that market, with its psychedelic nude woman.

Baen, 1986: Published just two years before Heinlein's death, this edition presents Lazarus Long on the cover, in his trademark kilt. The central facts or images from the story do not make it onto the cover. Lazarus Long is selling the book all by himself. (2)

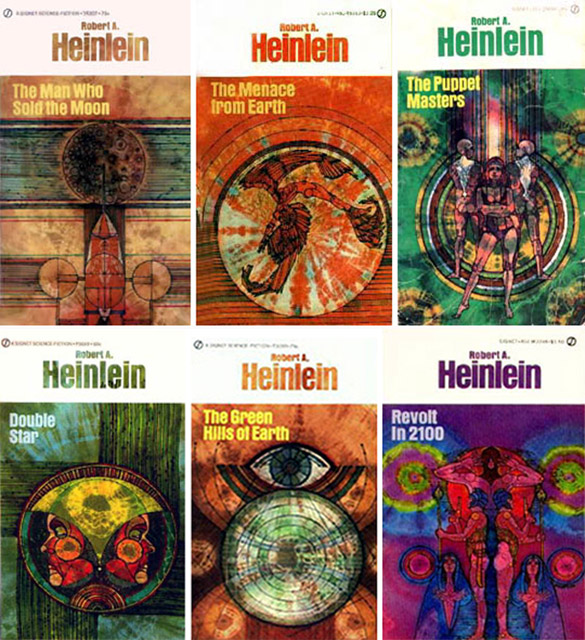

The cult of personality and the conforming reprint series: Just as Heinlein's name is 400 or 500% larger that the title on the 1986 Methuselah's Children reprint, the name of well known science fiction authors have grown over the years. This is another artifact of the unreveiwed status of science fiction. Such a bewildering array of science fiction is published, and in varying levels of quality, that name recognition becomes very important. Popular authors with large bodies of work sell books mostly on the basis of their names and reputation, not the inherent qualities of the work itself. While this can be true of other genres, the changing cover art of science fiction reprints highlights this in a number of ways. The most obvious is the conforming reprint series, where a large number of an author's works are given similar art and cover design elements. One of the best early example of this is the Signet reprints of Heinlein in 1970:

All had psychedelic art, most likely from the same artist, and were of uniform size and price. (3) This has a two-fold effect: the work of an author is easier to pick out at the point of sale, and book collecting "completists" (4) will buy entire runs.

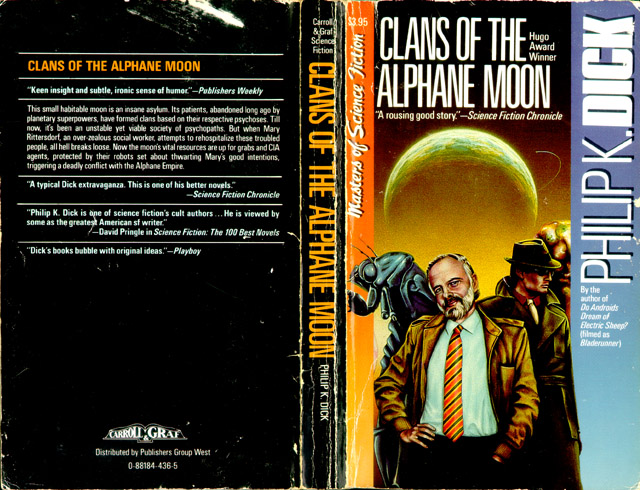

Philip K. Dick's Clans of the Alphane Moon

Since his death from a stroke in 1982, Philip K. Dick's reputation in science fiction and academic circles has steadily increased. Dick's prodigious output, political and religious beliefs, and colorful personal life have all contributed to his fascination for readers and researchers.

That Philip K. Dick is a major author in American fiction is without doubt. He published thirty-six novels during his lifetime, and over 140 short stories between the years 1952-1982. Since his death, nine additional novels have been posthumously published, as well as a five-volume collection that chronologically collects all of his published short fiction. Dick's work has been the basis of seven movies (most notably, Blade Runner (1982), Total Recall (1990), and the Steven Spielberg/Tom Cruise film The Minority Report (2002), one television show, a number of stage plays, and at least one opera. Dick himself has been the subject of a full length documentary, The Gospel According to Philip K. Dick. A search on the Modern Language Association (MLA) Bibliography database cites 141 articles with Philip K. Dick as their subject matter. Dissertation Abstracts notes twenty-six theses with Dick as their primary subject matter. Over two dozen serious critical works have been written on Dick, and two in-depth biographies.

When looking at the binding styles of science fiction over its most commercial period, Philip K. Dick is a fertile example. He went through the period when "mid-level" science fiction writers had little control over the editorial content and the packaging of their work (and being paid next to nothing), to the post-Star Wars boom of the late 1970's, to the cult-like following and critical attention he has enjoyed since his death.

His 1964 novel, Clans of the Alphane Moon is a fine lens through which to view the various periods and movements in the evolution of science fiction cover art. Clans is a very rich and subtle story of a bitter divorce between a man who cowers when challenged by his mentally ill wife, embedded in a science fiction backdrop that includes aliens, interstellar war, CIA robots, and a planet literally filled with mentally ill people. Chuck Rittersdorf, CIA robot programmer, is served with divorce papers from his wife Mary, a highly successful psychiatrist. She is leaving him in order to force him out of his well-loved, but low paying job. He moves into a shabby apartment next door to Lord Running Clam, a telepathic Ganymedean slime mold, who tries to help him work out the kinks in his life. Twenty years ago, Earth fought a war with the Alphane Empire, large sightless insects and the CIA still fears Alphane intrigue in retaliation. During the war, a small moon in the Alphane system was converted into a large insane asylum for the mentally ill of Earth. After the conflict, Earth abandoned the moon and its inhabitants. The Alphane Empire wants the moon back. Mary Rittersdorf leaves on a CIA mission along with a CIA robot called Mageboom to convince the inhabitants that rejoining Earth is in their best interests. The inhabitants for the moon, having long ago burned down the hospital in which they were confined, have broken up into different "clans" according to their respective mental illness. The Pares (paranoid schizophrenics) live a fortress called Adolfville; the Manses (manic-depressives) live in Da Vinci Heights, and so forth. There is so much action, so much intrigue, and so many characters, it is almost impossible to summarize. It is not one of Dick's masterpieces (5), but the tightly plotted spectacle where the frantic author keeps dozens of plates spinning is a large part of Dick's appeal, therefore is it representative of his work.

This overview is constrained to American editions.

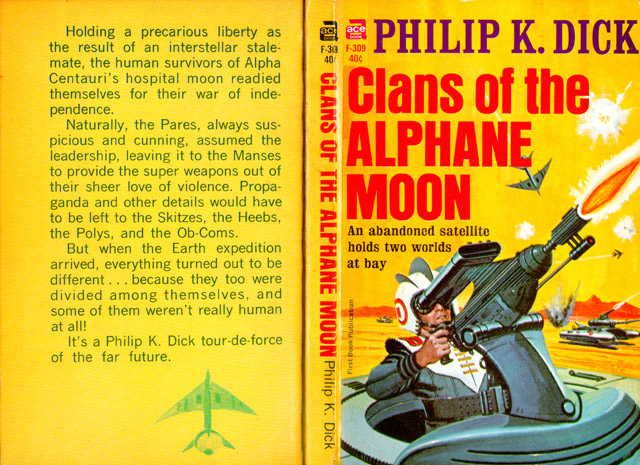

Ace, 1964: This is the first edition of the work. Dick received $750 on the acceptance of the outline and $750 upon delivery of the final manuscript. (Sutin, 121) The cover is garish, mostly reds and yellows. None of the central characters appear on the cover, but it does depict a very brief scene toward the end of the novel when a Manses tank attacks the CIA forces. The cover states, "an abandon satellite holds two worlds at bay". The cover and the back ad copy plays up the martial aspects of the plot, which is quite incidental to the story. The paper is very acidic, little better than pulp, and the cover was off center when glued to the text block.

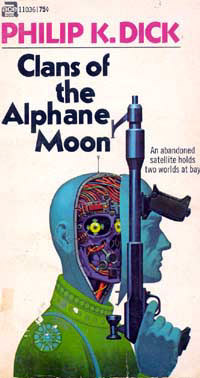

Ace, 1972: Reprinted eight years later, mostly likely in response to the attention given to Dick at the Vancouver science fiction convention. This cover plays up the Mageboom/CIA agent character. It preserves the front cover copy.

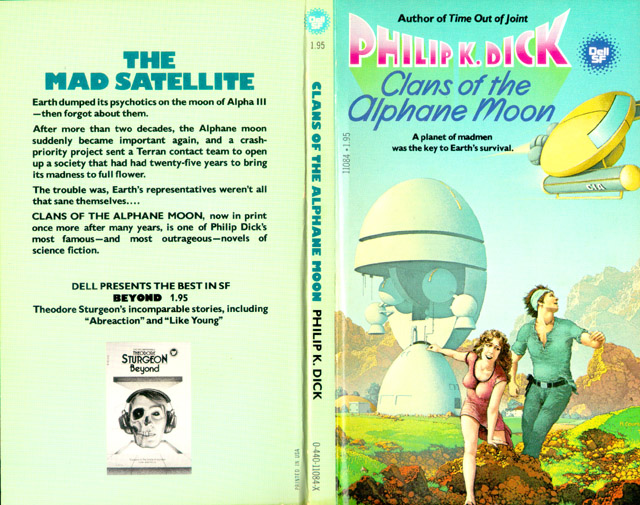

Dell, 1980: Eight years again pass before it is reprinted. Perhaps its reprinting was prompted by the pre-production of Blade Runner adapted from his 1968 novel Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? Chuck Rittersdorf is finally on the cover, running from his wife (in the flying ship) who is trying to kill him. The cover does play out a scene from the novel, and oddly it is a scene just before the Manses tank attack scene depicted (rather fantastically) in the 1964 cover. The cover copy paraphrases the 1964 and 1972 cover blurb: "A planet of madmen was the key to Earth's survival." The back ad copy continues to ignore that the Alphane moon plot is almost incidental to the real story of the Rittersdorf's divorce.

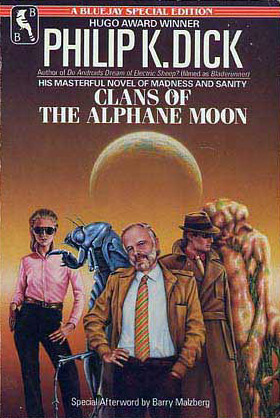

Bluejay, 1984: While all the proceeding editions were mass market paperbacks, this edition was issued as a trade paperback. It still had a hot-glued text block and cover, but the cover paper was thicker and coated and the text was printed on thicker paper, at least a leap forward in durability. This is the first cover to reflect the cult of personality as a marketing ploy. This edition was published in the wake of the success of Blade Runner (which the cover misspells as Bladerunner) and Dick's death the same year (1982.) Above the title, Dick's Hugo win for The Man in the High Castle is trumpeted. The cover is a representative of the work in that actual characters appear on the cover. To the left is Mary Rittersdorf and next to her is an Alphane. On the right is either Chuck Rittersdorf or the Mageboom robot and the shapeless, multicolored mass is Lord Running Clam (at 8 times of so of the size his is described as having in the novel). But front and center is Philip K. Dick himself, thrusting him into the spotlight and making all the characters seem to stem from him. The Bluejay reprints were a conforming series, with four other titles. (6) All of these reprints featured essays by science fiction writers that memorialize Dick and his body of work.

Carroll & Graf, 1988: Essentially a mass market reprint of the Bluejay trade paperbacks, this conforming series used the same cover art, but the image was cropped to add a very large "PHILIP K. DICK" on a blue field. Mary is gone from the cover, and so is most of Lord Running Clam. This printing also went back to the marginal construction techniques of mass market over trade paper. Only Mary, the character excluded from the cover art, is discussed on the back, along with more sophisticated discussion of the plot, but still focused on the interstellar war aspects of the narrative.

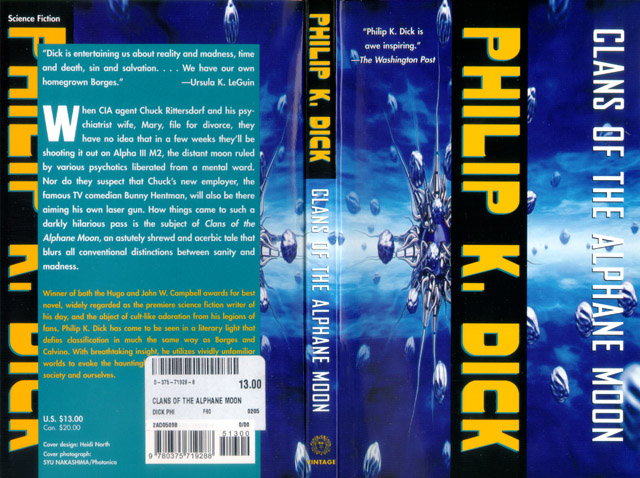

Vintage, 2002: A very large and ongoing conforming reprint series. (7) These trade paperbacks are still hot glued, but the paper tests as acid-free using a pH pen. The central black stripe down the cover with "PHILIP K. DICK" in bright yellow reflects the cult of personality mentality. The covers for the entire series are abstract and computer-generated, but the back cover copy is the real gem. Chuck and Mary's divorce is center stage and the reality of the plot being secondary to their plight is emphasized.

Robert A. Heinlein: Bindings as political speech

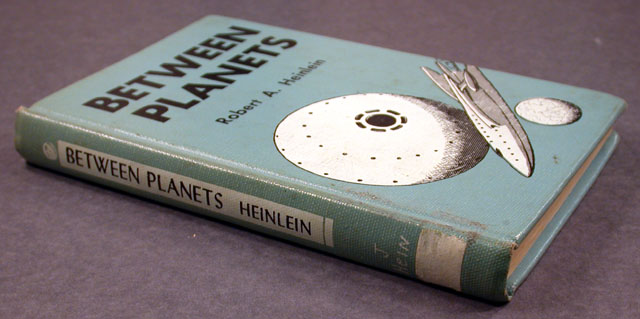

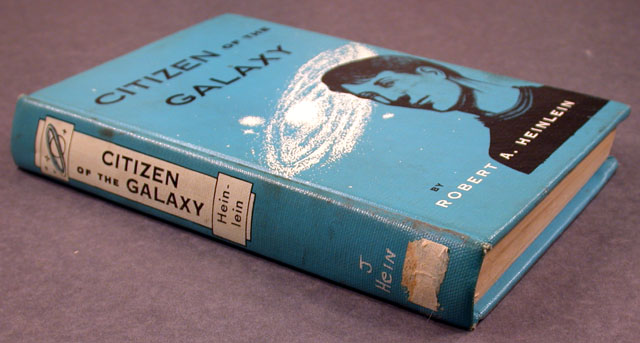

Between 1947 and 1963 Robert A. Heinlein produced fourteen novels that are collectively referred to as Heinlein Juveniles. (8) Twelve of the fourteen were published at Scribner's, and eleven were written specifically for the publishing house. The first, Rocket Ship Galileo, was written under contract for another publishing house but wound up at Scribner's. The next-to-last, Starship Troopers, was turned down by the editors at Scribner's as inappropriate for children. The last, Podkayne of Mars, was published in 1963, and its ending was so dark, the editor at Putnam pressured Heinlein into changing it considerably. But why was Robert A. Heinlein writing children's books to begin with? He was already well established when Scribner's approached him to do more juveniles after the mild success of Rocket Ship Galileo. And Rocket Ship, with its Nazis on the moon plot was just a boilerplate "boy's adventure novel" anyway, derided in Alexis Panshin's critical work Heinlein in Dimension as "a book that I would unhesitatingly give to an eleven-year-old but to no one older." (Panshin Chap. 3, Sec. 2) But the next twelve works, considered by some the finest work of his career, were written well enough to be popular with kids and adults alike. The last of which, Starship Troopers, when published, unchanged from its manuscript for Scribner as a juvenile, won the very adult Hugo award, Heinlein's first of four he would win.

As a futurist, Heinlein wanted humanity to get into space. Having studied physics and mathematics himself, he also felt that the so-called hard sciences should be pushed to young people (although at first he was only talking to boys). The juveniles became a way for Heinlein to stimulate interest in space and space exploration. The protagonists mirrored the target audience: 14-18 year-old boys, who, through no special talent, but rather hard work, rise to the challenge of the universe and excel. Science and math play large parts in these works, as well as the building of strong personal integrity and group loyalty. And they were popular, often being serialized in children's magazines like Boy's Life and Blue Book before being published. Their popularity is part of the reason that they were published in hardcover, an extreme rarity at the time, but another reason for the binding was libraries.

In the 1940s and 1950s, the social work model of librarianship was in full force. The contents of the library were more to uplift its patron, than entertain them. Science fiction was a trash genre, no more conceivable as being a part of collection development policy as was comic books or Bazooka Joe wrappers. But Scribner's and Heinlein set out to change that. The juveniles, from Space Cadet (1948) to Have Spacesuit - Will Travel (1958) were issued in first edition as a sort of proto-library edition format. Instead of hot glue or burst-binding on essentially pulp paper, the juveniles were given sewn text blocks, sturdy endpapers, thicker paper, interior illustrations, and illustrated covers that eliminated the need for dustcovers that tear, look shabby, or are automatically discarded.

The end product was a library-friendly edition made to withstand the rigors of regular use. The edition of Between Planets in my personal collection withstood 40 years of public library use before a short-sighted weeding project withdrew it in 1991, and I bought it at a library sale. Except for a few injudicious application of scotch tape, the edition is still very readable, and looks and smells better that some science fiction paperbacks published in the early 1990s. An interior page in Between Planets survived forty-two folds, and the corner still doesn't detach under a firm tug.

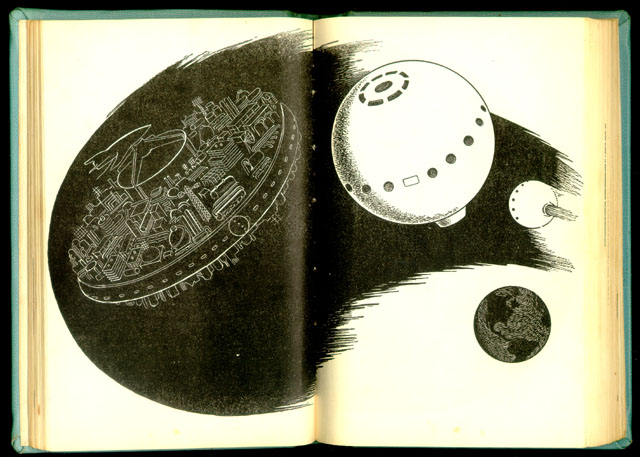

The artwork alone qualifies them as a medium rare binding. Clifford Geary created the cover and interior illustrations for eight of the Scribner juveniles, creating striking images with a scratchboard technique, where a dark material laid over a lighter and scratched away to create the image in negative. They are printed in a heavy, evocative black that stands out well on the page. The cover and interior illustration have never been reprinted in any of the numerous editions of the juveniles.

Heinlein just didn't let the bindings speak for themselves; he also lobbied librarians directly to give science fiction a chance. In a 1953, his article "Ray Guns and Rocket Ships" appeared in The Bulletin of the School Library Association of California. The same article was reprinted the next year in Library Journal. In it, he argues for the inclusion of science fiction in libraries and that the genre had transcended its "low" origins.

The Heinlein juveniles represent a specialized binding and print edition designed to carry political speech, namely the futurist aspirations of the author. Attractive to the eye and built to withstand the rigors of use, science fiction is transformed from a "disposable" genre in a print medium with built-in obsolescence to a literature about the future in a vehicle designed to make it there intact. Science fiction grew up, and its bindings had to as well.

Conclusion

The best approach, it would seem, in light of the research potential of science

fiction in its original bindings, is to treat each edition as a unique artifact.

This may not be possible in a circulating environment, but in the special collection

and archives environment, it should be expected. Science fiction, especially

in its paperback and illustrated hardcover forms, is a type of medium rare binding

and should be recognized as such when preservation is an issue.

Works Cited

Benson, Gordon Jr. and Phil Stephensen-Payne. Philip K. Dick, Metaphysical Conjurer: A Working Bibliography. San Bernardino: Borgo Press: 1990.

Dick, Philip K. Clans of the Alphane Moon. Ace: New York, NY: 1964.

_______. Clans of the Alphane Moon. Ace: New York, NY: 1972.

_______. Clans of the Alphane Moon. Dell: New York, NY: 1980.

_______. Clans of the Alphane Moon. Bluejay: New York, NY: 1984.

_______. Clans of the Alphane Moon. Carroll & Graf: New York, NY: 1988.

_______. Eye in the Sky. Ace Books: New York, NY: 1975.

_______. Lies, Inc. Gollancz: London: 1984.

_______. "The Missing Pages of The Unteleported Man." Philip K. Dick Society Newsletter, No. 8 (Sept. 1985): pp. 2, 13.

_______. The Unteleported Man. Ace Books: New York, NY: 1966

Heinlein, Robert A. "Ray Guns and Rocket Ships." The Bulletin of the School Library Association of California. 24.1 (Nov. 1952) p. 11-15.

_______. "Ray Guns and Rocket Ships." Library Journal. (July 1953): 1188-1191.

Ormes, Marie Guthrie. Robert A. Heinlein: A Bibliographical Research Guide to Heinlein's Complete Works. Diss. U. of KY, 1993.

Panshin, Alexei. "Heinlein in Dimension." Alexei Panshin's Abyss of Wonder. 1968. 29 Oct. 2003 <http://www.enter.net/~torve/critics/Dimension/hdcontents.html>.

Sutin, Lawrence. Divine Invasions: A Life of Philip K. Dick. Citadel Press: New York, NY: 1989.

Tucker, Wilson. The Long Loud Silence. Dell: New York, NY: 1952.

_______. The Long Loud Silence. Lancer: New York, NY: 1969.

Endnotes

1. Robert A. Heinlein, Future History Sequence:

The Past Through Tomorrow (1967)*

I Will Fear No Evil (1970)

Methuselah's Children (1941)

Orphans Of The Sky (1964)

Time Enough For Love (1973)

The Number of the Beast (1980)

The Cat Who Walks Through Walls (1985)

To Sail Beyond Sunset (1987)

*A short story collection arranged by internal chronology. The edition also includes Methuselah's Children, but I have placed in the proper sequence in novel form.

2. Lazarus Long has become Heinlein's most enduring and popular character. Long relates his life in 1973's Time Enough For Love, set in the 47th century, when Long is the oldest living human being at 2700 or so years of age. All of Heinlein's last three novels concern the character in someway, and his last published work, To Sail Beyond The Sunset (1987) is the "autobiography" of Lazarus Long's mother.

3. Twelve Heinlein novels or short story collections were reprinted in this edition:

The Door Into Summer

The Menace From Earth

Waldo and Magic, Inc.

Assignment in Eternity

Revolt in 2100

The Puppet Masters

Methuselah's Children

The Man Who Sold The Moon

The Green Hills of Earth

Double Star

Orphans of the Sky

Beyond This Horizon

4. One type of completist enjoys reading by author and will make it a goal to read everything published by an author. Many things are kept in print by the demand of completists. Others are "edition" completists, who will buy or attempt to collect all editions of a single work or all the editions of an author's entire body of work. The economic feasibility of creating editions for the consumption of completists was proven by the success of Image Comics in the early 1990s. Some of their comic titles were issued with multiple (in one case thirteen) covers and all sold briskly, with collectors buying multiple (or all) variant covers of that same comic.

5. Dick's generally agreed upon masterpieces are:

The Man in the High Castle (1962)

The Three Stigmata of Palmer Eldritch (1964)

Time Out of Joint (1959)

Ubik (1969)

VALIS (1981)

6. The others are:

Dr. Bloodmoney, or How We Got Along After the Bomb

The Penultimate Truth

Time Out of Joint

The Zap Gun

7. Vintage has already printed twenty-one of Dick's novels, and an unspecified number still to come. This means that 61% of his science fiction novels have appeared in this edition. Below is a full listing of this conforming reprint series:

VALIS

The Divine Invasion

The Transmigration of Timothy Archer

Radio Free Albemuth

Dr. Bloodmoney, or How We Got Along After the Bomb

The Man Who Japed

Ubik

The World Jones Made

A Maze of Death

A Scanner Darkly

Now Wait for Last Year

Time Out of Joint

The Three Stigmata of Palmer Eldritch

Confessions of a Crap Artist

The Game Players of Titan

The Man in the High Castle

Clans of the Alphane Moon

Flow My Tears, the Policeman Said

Counter-Clock World

The Zap Gun

The Simulacra

8. Heinlein Juveniles:

Rocket Ship Galileo, Scribner's, 1947

Space Cadet, Scribner's, 1948

Red Planet, Scribner's, 1949

Farmer in the Sky, Scribner's, 1950

Between Planets, Scribner's, 1951

The Rolling Stones, Scribner's, 1952

Starman Jones, Scribner's, 1953

The Star Beast, Scribner's, 1954

Tunnel in the Sky, Scribner's, 1955

Time for the Stars, Scribner's, 1956

Citizen of the Galaxy, Scribner's, 1957

Have Space Suit -Will Travel, Scribner's, 1958

Starship Troopers, Putnam, 1959

Podkayne of Mars, Putnam, 1963