Project Editors

Colleen Bailey

Trey Conatser

Hayley Harlow

Katie Kirk

Elle Kowal

Stephanie McCormick

None of them begin to have enough. This person who spoke with me said that anyone who went in had to carry their own food and that to see them starving still as when the fight was on, starving after their years of agony, starving now when all prated of peace, was to watch the needless death of a nation.

—Mary Breckinridge, Letter to Katherine Breckinridge, 23 March 1919

Mary Breckinridge’s experience in France, and the mark her work left on the country, went far beyond providing routine medical care for ailing children and their families. It was equally defined by the reverence she felt as she viewed the landscape’s scars firsthand, her personal connections to the patients she worked with as she learned more of their interests and backgrounds, and her tireless drive to rebuild thousands of lives like theirs from ruins that, even though the war had ended, still bode danger for those in their shadows.

If we can tide them through the bitter time ahead as they stagger to their feet and find themselves we will be helping not France alone but the world.

— Mary Breckinridge, "Program of Child Welfare," 19 July 1919

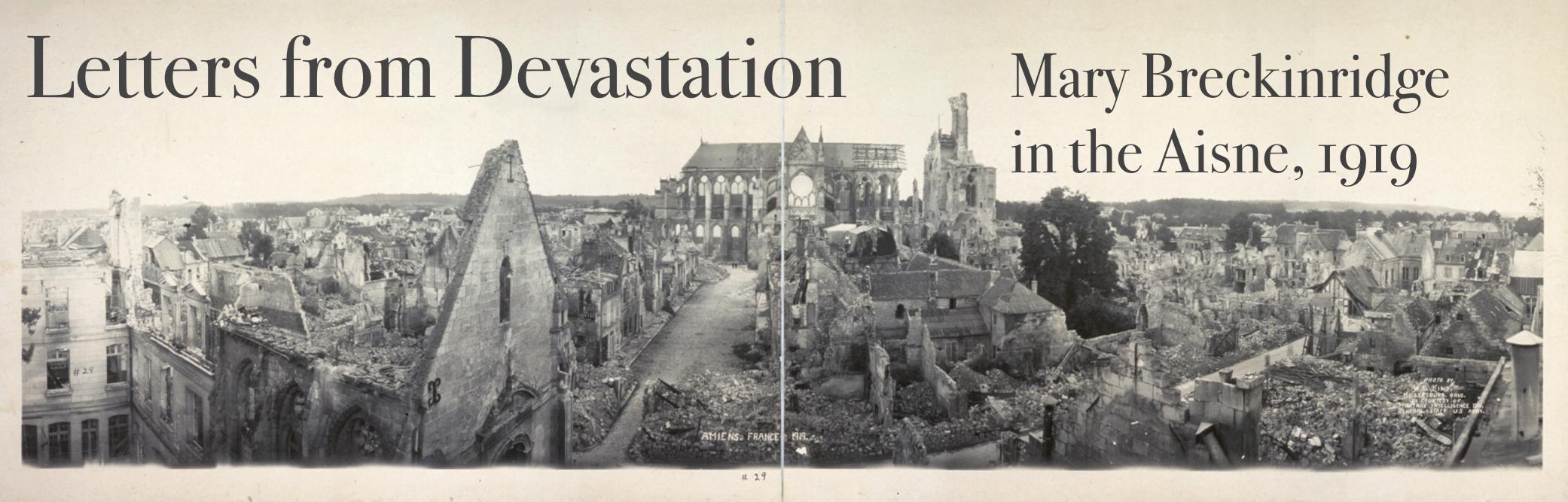

Breckinridge's experiences in the Aisne (a devastated region northeast of Paris) in the wake of the first world war are evocatively recounted in her autobiography Wide Neighborhoods and authoritatively contextualized with respect to her later life's work in Melanie Beals Goan's Mary Breckinridge: The Frontier Nursing Service and Rural Health in Appalachia. Indeed, the chaotic and surreal work amid the ruins of an unprecedently devastating war contributed significantly to Breckinridge's founding of the Frontier Nursing Service and the subsequent advancements at the nexus of nurse-midwifery, public health, and social justice in Appalachia. The letters in this edition provide a perspective from the day-to-day that enriches our understanding of Breckinridge's history (as well as the histories of postwar France and public health nursing) with the drama of lived experience. Letters from Devastation takes the year 1919 as its focus, from the moment that Breckinridge set foot on French soil to the end of the year as her public health program began to gain momentum despite the considerable obstacles that she and her team faced.

In the first letter of 4 January, directed to a representative of the Shepperd Pratt Hospital, Breckinridge politely passes on an opportunity to co-author a book on child welfare, a field in which she already had made a name for herself in the United States. Instead, she writes, she will be working with the American Committee for Devastated France for an unknown amount of time. Thus begins her odyssey in the devastated lands. Once she arrives in Europe she writes to her family about her patients and the people of France with particular attention to the war's effects on public health. Accounts of social events both personal and professional contrast with impactful descriptions of the ruined terrain in which she finds herself. The first order of business, Breckinridge recalls in Wide Neighborhoods, was to provide people with “food, clothing, bedding, and a few household utensils, but especially food” (78). In the letters we read a consistent concern for proper nutrition among war-devastated families with young children. Breckinridge's organization responds with supplies and regular check-ins, but most notably in this year she arranges for the delivery of goats (for milk) to rural families. Conventional medical care as we understand it in the twenty-first century is not frequently noted, especially in the earlier letters. However, later in the year, Breckinridge received permission to begin a dedicated program of combined nursing and nutritional care for children under six and expectant or nursing mothers (83).

By year's end, Breckinridge describes a country still heavily damaged but beginning to recover, thanks in part to her efforts. In a late November letter, she speaks of her ongoing and future plans for raising awareness and soliciting donations in the United States, as well as introducing more nurses to the regions in which she works. By December, Breckinridge oversees six nurses responsible for four counties. While it is clear that much more work remains, the nursing efforts became “a fully generalized service” under Breckinridge’s watch, and the goat campaign also continued to make progress as Breckinridge assumed a more managerial position in the Aisne (91).

France, however, was certainly not Breckinridge's first experience with travel. Born in 1881 in Memphis, she grew up in Washington, D.C., but moved to Russia, Switzerland, and Connecticut before finally returning to her family’s home in Arkansas in 1899. In 1904 she married her first husband, Henry Morrison, who died two years later after developing appendicitis. After his death, Breckinridge enrolled in St. Luke’s Hospital School of Nursing in New York City. Two years after her graduation, in 1912, she met and married Richard Ryan Thompson, the president of a women’s school in Eureka Springs, Arkansas, and worked for the next two years at the school teaching French and hygiene. Between 1914 and 1918, the couple had two children, a son and a daughter, but both died tragically young deaths. Breckinridge soon after separated from Thompson and reassumed her maiden surname. Devastated and determined to honor her children's memory, she devoted the rest of her life to helping children in need.

Six months before the end of the war, Breckinridge began work as a public health nurse in Boston and Washington, D.C., where an influenza outbreak had taken hold. She managed a team of five nurses and numerous aides. In late 1918, however, she felt called to France, and found herself there a few weeks after the war's end. During her three years abroad, she created programs to provide assistance for malnourished children and pregnant women. For one of these, the Child-Hygiene and Visiting-Nurse Association, she was awarded the Medaille Reconnaissance Français (Medal of French Gratitude), a civilian award designed to honor those who had come to the aid of the needy without any obligation to do so.

The United States—especially the isolated regions such as Appalachia—did not have a precedent for the kind of public health nursing nor the nurse-midwifery that Breckinridge had practiced and learned about in Europe. Convinced that rural American children would benefit equally from the assistance of trained nurse-midwives, Breckinridge returned in 1921. After studying for four years in New York City, England, and Scotland to further her knowledge in public health, she moved to Leslie County, Kentucky, and founded the Kentucky Committee for Mothers and Babies, later known as the Frontier Nursing Service, which is now remembered as her most significant achievement. This service, which brought modern nurse-midwives into one of the most remote and underprivileged regions of the nation, led to a precipitous drop in maternal and neonatal death rates, well below the national average. Breckinridge served as the director of the Frontier Nursing Service for 37 years until her death in 1965. The Frontier Nursing Service remains strongly in operation today with six locations in Eastern Kentucky and the thriving Frontier Nursing University.

Public health and nursing looked quite different at the beginning of the twentieth century. While the discipline was slowly becoming more organized, obstetric public health nurses still could not deliver babies. They cared for the antepartum, intrapartum, and postpartum patient, and were required to call in the doctor for the actual delivery and any further complications or treatments. In the United States, nurse midwives were not trained alongside physicians as they were in Europe, and they faced a general bias towards male expertise. But isolated communities needed medical care for mothers and children. Nurse midwives, unlike nurses, could deliver the baby and care for the mother and child throughout the process. Though urban residents had access to classically trained physicians and other healthcare professionals, the rural population did not have the same resources close at hand, and often could not afford healthcare or the transportation needed to get to the cities. People in rural communities were, as they are still, often self-reliant: cultivating their own resources, communicating sparingly with outsiders, and traveling more slowly and indirectly over wilder terrain. rent.

Much of what became the Frontier Nursing Service is indebted to European models. Historically, nurse midwives enjoyed a comparatively privileged social standing in France. In Wide Neighborhoods Breckinridge recalls that “it seemed off to me that in France where the training of midwives was excellent, and constantly improving, training of nurses should be neglected. In the United States, it is the other way around. Over here one has to push the need for midwifery” (95). In 1919, nurse midwives from across Europe met to establish the International Confederation of Midwives (ICM) to strengthen their profession and promote the expansion of midwifery worldwide. This organization worked to outline competencies for nurse midwives to ensure that their practice was consistent with a classically trained physician's. Nurse midwives remain a prominent part of the French healthcare system today. Most have complete autonomy, only seeking a doctor’s advice with abnormal cases.

Breckinridge was trained as a nurse midwife at the British Hospital for Mothers and Babies in London. At first, she sent her nurses to Britain as well to be trained as nurse midwives; however, after the outbreak of World War II she instead began training nurse midwives in the United States through her Frontier Nursing Program. This sparked the opening of many more nurse midwife programs across the nation. The Frontier Nursing University continues to grow today and currently is expanding into Versailles, Kentucky: a fitting, albeit unintentional homage to Breckinridge's experiences in France. Nationally, the profession of nurse-midwifery continues to grow due to an increasing emphasis on preventative healthcare and the relatively low cost of nurse-midwife-assisted births.

"It is, in fact, one of the ironies of Kentucky history," writes Anne Campbell, "that the miseries of war-devastated France contributed to the uplifting of medical service in the mountains of Appalachia. As with Breckinridge's personal life, tragedy was transformed into altruism" (275-76). World War I had devastated the French countryside and left the population without food, shelter, and, in many cases, without a functional urban infrastructure, economy, and agriculture. Among the many dearths of a post-war populace, medical attention was a dire need and in a very real and widespread sense, a life-or-death situation.

You can not conceive of how the earth itself is torn to pieces on the battlefields. It engulfed thousands like an ocean and it is heaving and torn and broken like giant waves.

—Mary Breckinridge, Letter to Katherine Breckinridge, 25 October 1919

Breckinridge served with the aptly named American Committee for Devastated France, or CARD (Comité Américain pour les Régions Dévastées de France). Co-founded by Anne Morgan and Anne Murray Dike, the Committee originated from the Civilian Division of the American Fund for French Wounded in November of 1916 and sought “to establish a Community Center in the devastated area of France, to which a knowledge of the needs of the community would come, and from which would go the means to meet those needs” (American Committee, Inc. 2). The Committee served five of these community centers in the Aisne region, including Breckinridge’s Vic-sur-Aisne, with headquarters officially located at the 17th century Chateau de Blérancourt.

The Committee aided the war-torn regions of France in response to the changing needs of the people, whether it was providing emergency relief, serving as nurses in hospitals, or assisting in the evacuation of villages. Mary Breckinridge's letters from 1919 provide evidence of these activities, indicating that she and fellow Committee workers supplied food and clothing among other necessary items, with support from organizations such as The American Red Cross, the Commission for Relief in Belgium, and the American Field Service. By March of 1919, the five relief centers—Chateau Thierry, Vic-sur-Aisne, Blérancourt, Soissons, and Laon—had distributed food supplies to over 100 villages (American Committee, Inc. 2-4).

I don’t see how any person or any organization ever got the idea that we weren’t needed, we Americans I mean, and our supplies, in France any more.

—Mary Breckinridge, Letter to Katherine Breckinridge, 23 March 1919

As Aisne was a farming region, the Committee also provided agricultural aid in order to reclaim the soil and restore abandoned farms to operation. Yet in addition to her first-hand accounts of the war damage throughout the land, Breckinridge gives us beautifully detailed descriptions of the French countryside as insight into her own experience of the rural landscape despite its need for restoration. During her time as a Committee member, she contributed to working with the local communities and engaging the community members themselves for the purpose of rebuilding and returning the communities to a self-sustaining state. Ultimately, the efforts of Mary Breckinridge and the larger Committee served an immeasurable role not only in the restoration of war-torn France but also in providing necessary public health care to thousands affected by the war who otherwise may not have received the help and supplies they needed.

Breckinridge may have written from devastation, but she worked tirelessly to foster new growth. There is no image more fitting or meaningful for her mission than what we encounter among a description of her room as she writes to her mother in an April evening. Among the simple and spare furnishings and as the hush of darkness settles into the countryside, Breckinridge notes:

On the table is an exploded shell, beautiful brass like them all, filled with spring flowers, violets and primroses the children gave me at Montigny.