To Katherine Breckinridge, 12 April 1919

digitized, transcribed, encoded, and annotated by Katie Kirk

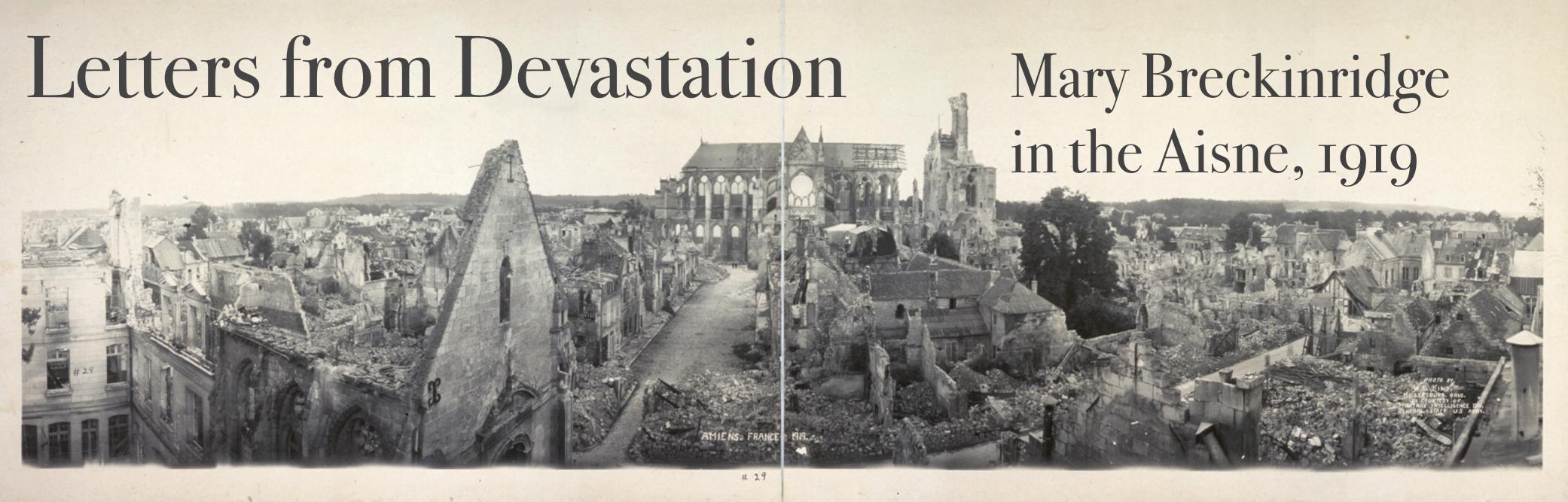

This letter, which Breckinridge wrote to her mother, primarily talks about everything that has happened over the course of the past week. Breckinridge talks about having a variety of visitors who came over specifically to see the nursing-related work that she and her committee have been doing; she also speaks highly of her committee, saying that their strengths effectively lie in their diversity. By this point, it is clear that she and her other nurses are being highly regarded for their work in France. Breckinridge also speaks about her visit to the Compiégne military hospital and recounts a tragic event that occurred during her time there—while she was at the hospital, a nineteen-year-old boy accidentally picked up a grenade that blew the three middle fingers on his hand completely off. She speaks of his bravery, his parents' tears, and the local peasants who advised his parents to not cry until he was actually dead. (It is unclear whether the boy was actually killed.) In the second part of the letter, Breckinridge talks about the Duvauchelle family, a family who is very poor and whose child had previously died of pneumonia. She describes the acts of charity she has provided for them in order to help get their family back on its feet. Finally, Breckinridge ends the letter with a description of the surroundings in her room, including a strikingly poetic description of the fact that she has spring flowers on her desk that sit in an exploded bombshell. Overall, this letter serves to inform about the importance of Breckinridge's work while also specifically emphasizing the honors she and her colleagues have lately been receiving.

My darling mother:

There has been nothing from you since I wrote you

last Saturday or Sunday the olletter of which I now enclose carbon with

this. I shall feel easier in my mind when your letters are going to

the bank instead of to the committee, although some may be lost in any

event and it would be better to repeat anything important. By the way

I want another copy of “Breckie” as one of those I brought over was,

as I wrote you, defective and so please send me a good copy in care of

the Comptoir National d’Escompte. We will see if it gets through all

right. Your second Scribners reached me yesterday safely and I enjoyed

the end of Kate Douglas Wiggin’s story.

We have had an attractive Y.M.C.A. couple visinttiting us

from Chicago and liked them immensely while of us they formed so high

an opinion that they speak of us as the “Hand_picked committee.’” We

are so variegated a crowd that it always strikes anyone coming in. In

college units everyone has the college in common, in medical units they

have that, but no two people in our unit have every led the same general

kind of life or done the same things or are fitted with the same mental

equipment. I saw at Blerancourt the day Petain honored us there those of

the committee who crossed with me, Mrs. Hillis now at Soissons, Mrs.

Kittridge, now at Laon, and Mrs. Ham, now at Blérancourt. All have had the

grip and bronchitis. Did you know that we wear our horizon blue uniform

by special permission of General Pétain himself and that only one other

organization is allowed to wear the same color and that is the Pienetre

des Bléssés, the one in which Geertrude Atherton and Mrs. Ernest Seton

Thompson are interested, one of whose stranded chauffeurs, a woman of

course, spent a night with us this past week on her way back from the

Compiegne military hospital. I was at this hospital last Sunday. I had

planned for a little quite walk over a lovely field, with eyes carefully

bent to the ground to avoid hand greanades, and then up a safe road to a

wood which had been strongly foorrtified. It has the most fascinating

trenches and dugouts where we have been before, whole rooms in the ground

and a chapel and the front of the entrances built of cement and stone.

They are on a hill which the French held for years protecting our KRRisne

valley, this section, which was overun early in the war and again last

June, where Vic_ is—for Vic was not held by the Germans for years like

the Blérancourt section which was not evacuated and destroyed until

191877, and thenof course evacuated again last spring. Vic was evacuated in

1914, reoccupied, evacuated again the last of May 1918. Various villages

around and between shared the fate of one or the other of these. or had************

Well, to return, I began my walk and was climbing the hill when I heard

one f**of our camions rolling up the road below me, then it stopped and

Braly waved me down. Another man, this time a boy of nineteen, had been

exlpploeddeded, our doctors were away, and I was to get him and take him to

Compiegne to the military hospital there after dressing his wounds first.

It turned out not to be a very terrible injury, and was from one of those

detonators, not a granada**e—but from one thing or another we get them

every few days. This boy picked up the detonator not knowing what it was

(they look like nails) and it exploded in his hand taking off the three

middle fingers and tearing up the hand a good delaal. I gathered up the

poor gffragments in the dressings I had brought, for he sat with it wrapped

in a towel, and he was the pluckiet thing you can conceive of, never

a complaint or a gesture or any words except in answer to questions. His

father and mother weppedt**t** over him, the father kissing him over and over

and saying: "Good bye my beautiful." The mother cried and a neighbor said

Aisne peasants. The hospital at Compiégne is one of those ghastly,

vast places with constantly shiftin people in charge where no one is

responsible for any one else and nobody knows where things are. I haven't

time to describe it now. We constantly take wounded people to it.

I want to tell you about the Duvauchelle family of whom

I wrote frequently in past letters, whose little baby died of pneumonia

and who were at their last ropes when I advanced a hundred frames of

their indemnity refugee money. Well, now the father can work again and is making

good wages on the rebuilding work and their back indemnity refugee money has been

paid up as the result of a letter I wrote about it to the prefet at Laon

and which Miss Parsons signed for me, and the first thing Madame Duvau—

chelle said when she got it was: "Now I will pay the hundred francs you

advanced." Her having had it those few weeks meant ease of mind instead

of desperation for there wasn't a sou in the house and her husband had

been ill and was still not working and I never will forget the great sob

I heard from him when he learned that Itthey were to be helped until they

could stand alonge. I was talking to her, he never said a workdd, there

was just that sob. I had just learnt that there was nothing in the

house for supper and had been only bread the day before. And there were

four children.

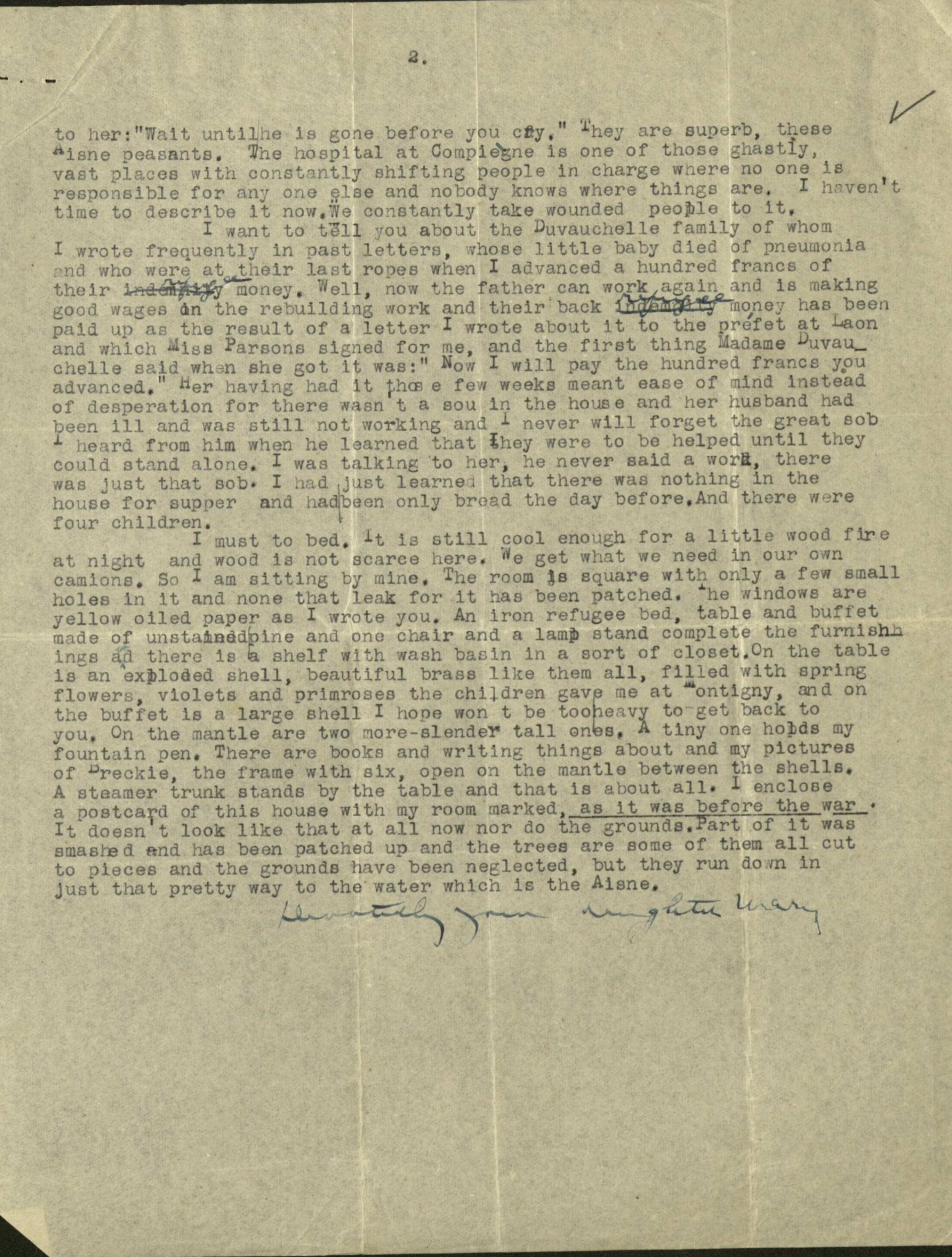

I must to bed, it is still cool enough for a little wood fire

at night and wood is scarce here. We get what we need in our own

camions. So I am sitting by mine. The room jiis square with only a few small

holes in it and none that leak for it has been patched. The windows are

yellow oiled paper as I wrote you. An iron refuge bed, table and buffet

made of unstanedineined pine and one chair and a lamlpp stand complete the furnish—

ings and there is a shelf with wash basin in a sort of closet. On the table

is an exlpploedded shell, beautiful brass like them all, filled with spring

flowers, violets and primroses the children gave me at Montigny, and on

the buffet is a large shell I hope won't be too heavy to get back to

you. On the mantle are two more-slender tall ones. A tiny one hopllds my

fountain pen. There are books and writing things about and my pictures

of Breckie, the frame with six, open on the mantle between the shells.

A steamer trunk stands by the table and that is about all. I enclose

a postcard of this house with my room marked, as it was before the war.

It doesn't look like that at all now,nor do the grounds. Part of it was

smashed and has been patched up and the trees are some of them all cut

to pieces and the grounds have been neglected, but they run down in

just that pretty way to the water which is the Aisne.

Devotedly your daughter Mary