The Problem of Faithless Electors and Other Crazy Electoral College Scenarios

By: Roger Morris

When all the votes are counted and we have a President-Elect, our long national nightmare, the 2016 election, is supposed to end. However, there is a small chance that no candidate could receive the requisite number of electoral votes, 270, to win the election outright.

In many states (including Kentucky), electors in the Electoral College are under no legal obligation to vote for the candidate chosen in the statewide vote. Electors who vote for someone other than who won their state’s popular vote are known as Faithless Electors. This phenomenon occurs more often than the public probably realizes. In 2004, one elector from Minnesota cast an electoral vote for Democratic Vice Presidential nominee John Edwards instead of the candidate who won that state, John Kerry. In 2000, there was one abstention from the Electoral College when a Washington D.C. Faithless Elector chose to refrain from casting a ballot in protest of Washington D.C.’s lack of voting representation in Congress. There have been 157 instances of Faithless Electors as of November 2016, including in nine elections since 1948. But have no fear; a Faithless Elector has never swung the outcome of an election.

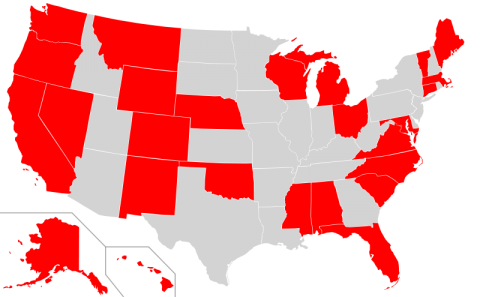

Twenty-nine states and the District of Columbia now have laws that bind electors to the candidate that wins their state. For example, in Utah an elector is considered to have resigned and their vote not recorded if they vote for a candidate not nominated by the same political party of which the elector is a member. Some states merely require electors sign a pledge that they will cast their vote for the candidate that wins their state, but some states go further and impose civil or criminal penalties. In New Mexico, a Faithless Elector is subject to a fourth degree felony charge. But there are also strong arguments that binding electors to vote in a certain way is unconstitutional.

Even before any votes have been cast, there is already the potential for at least one Faithless Elector. One Democratic elector from Washington State has publicly said that he will not vote for Hillary Clinton if she wins his state’s popular vote. This former Bernie Sanders supporter would face a $1,000 fine if he were to not vote for Hillary Clinton in this situation. In a very close election, this Elector may feel pressure to vote for Hillary Clinton despite his reservations because not doing so could result in a President Donald Trump or President Evan McMullin.

The mathematically astute may be wondering what happens if there is a 269-269 tie in the Electoral College or if a third candidate, like Evan McMullin, wins a state and no candidate receives a majority in the Electoral College. If this were to happen, the election would be thrown to Congress in what is called a “Contingent Election.” This has only happened twice in American history: 1800 and 1824. The Twelfth Amendment lays out how the process works.

The new Congress elected on November 8th would select the new President and Vice President, assuming the Vice President does not reach the requisite amount of electoral votes as well. The new Senate would elect the Vice President by deciding between the two Vice Presidential candidates with the most electoral votes and will cast a straight up-or-down vote. In addition to the Contingent Election of 1825, the Senate had to select the Vice President in the Contingent Election of 1837. That year some Faithless Electors refused to vote for the President-Elect’s running mate, which threw the selection of the Vice President to the Senate. (There was no Contingent Election for Vice President in 1801. This was before the Twelfth Amendment was passed and the Vice Presidency was won by the second place vote recipient for President in the House.)

The newly elected House of Representatives would elect the next President. Each state delegation will cast one vote, so all the members of a state’s House of Representatives delegation vote and the candidate who wins a majority of the delegation will earn the delegation’s single vote. According to the Twelfth Amendment, the House chooses among the three highest vote recipients in the Electoral College, so if Evan McMullin were to win the state of Utah, as polls suggest he might, Mr. McMullin would be one of the three options from which the House may choose. For a candidate to emerge from this process and become the next President, he or she has to earn a majority of state delegations’ votes. If after one round of voting no candidate has a majority, the process continues until there is a winner. In the Contingent Election of 1801, it took 36 rounds of balloting for Thomas Jefferson to become the 3rd US President.

This process also leaves open the possibility that the offices of the Presidency and Vice Presidency could be filled by people of two different political affiliations. This possibility would depend on which parties control each chamber of Congress. If Democrats were to take over the Senate this election and Republicans maintained control of the House, then if a Contingent election occurred there is a chance of a Trump or McMullin administration with a Vice President Tim Kaine. If this were to occur it would be the first time since the John Adams administration (1797-1801) that people of different political parties occupied the top two offices of the executive branch. (Although, this occurred at a time when Presidents and Vice Presidents were not elected as a ticket.)

Here is an even crazier scenario: if no candidate earns a majority of state delegation votes in the House, whoever the Senate selected as Vice President would become the President on Inauguration Day. And, if both the Senate and House cannot decide on a President and Vice President, the Speaker of the House, as the person next in the line of succession, would become the President of the United States. Given that House delegations vote as states and there are 50 states with 100 senators there are several possibilities for ties and gridlock.